Fr. Giussani (1922-2005)

“Looking for Beauty, He Found Christ”

The journey of a man who lived and proposed Christianity as an encounter, an event and a love story.A Friend in Leopardi

Giussani entered the seminary at the age of eleven, and was ordained a priest on May 26, 1945, by Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster. During high school, he fell in love with the study of literature, especially the works of the poet Giacomo Leopardi, because his “questions seemed to overshadow all others for me.” So great was his passion that he learned all of Leopardi’s poetry by heart and spend entire periods of time studying only that. Then, “then at 16 years old I discovered the key to reading his poems, those poems that made him the most striking companion along my religious itinerary,” (A. Savorana, The Life of Luigi Giussani p. 44).

His intuition began during a class on the prologue of the Gospel of John (later Giussani himself would refer to the occasion as his “beautiful day”), when he heard the professor say, “the Word of God, in other words that of which all things are made, was made flesh; and so, beauty was made flesh, goodness was made flesh, justice was made flesh, life and truth were made flesh. Being is not in a Platonic realm of ideas, it became flesh, and it is alive among us.” At that moment, Giussani remembered the hymn by poet Leopardi, To His Lady: “In that instant, I realized that Leopardi expressed – eighteen hundred years later – the begging for that event which had already happened, which St. John announced, ‘The Word was made flesh’.” (cfr. L'avvenimento cristiano. Uomo Chiesa Mondo)

This passion for beauty and attention to everyday activities were two of the characteristics of his personality that most impress those who had the chance to meet him in person. He himself said, “if beauty is the splendor of truth, then our taste, our aesthetic enjoyment is the modality through which man perceives truth.” (Certi di alcune grandi cose [Certain of a few great things]).

The Word of God was made flesh; and so, beauty was made flesh, goodness was made flesh, truth were made flesh.”

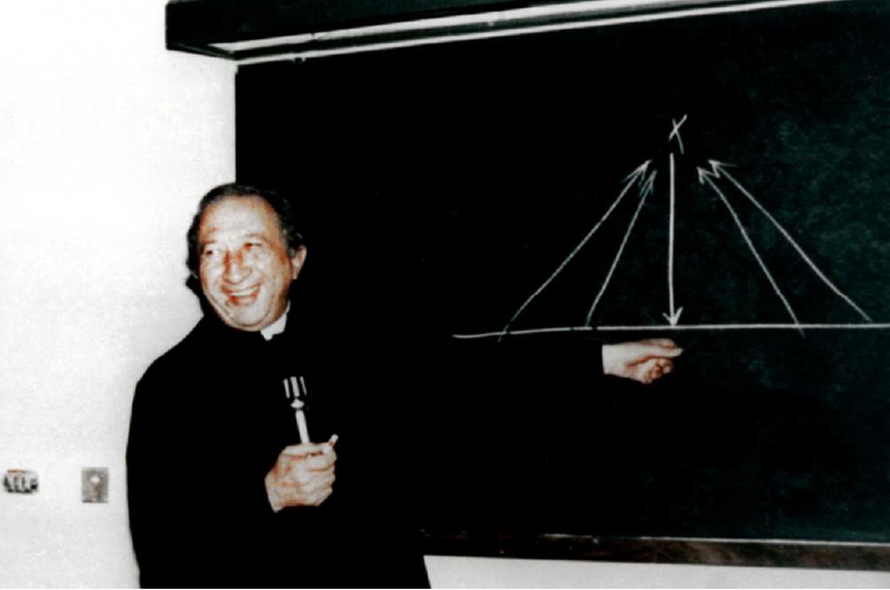

Faith and Life

This impetus of life, as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Benedict XVI, would explain, was the fruit of his personal relationship with Christ. “This love story which is the whole of his life was however far from every superficial enthusiasm, from every vague romanticism.” After his priestly ordination, his superiors decided the young Giussani should stay at the seminary to continue his studies and begin teaching. In 1954, he completed his doctorate in Theology, with his theses on Man’s Christian Sense According to Reinhold Niebuhr (cfr. American Protestant Theology: A Historical Sketch). During that time, Giussani came to realize that underneath the apparent flourishing of Catholicism in Italy, with churches full and thousands of votes going to the Christian Democrat party, a deep crisis was already brewing: the separation of faith from daily life, the contrast between tradition and current ways of thinking, and morality reduced to moralism. Though they knew the doctrines and dogmas, young people were deep down “ignorant” of the Church and were growing distant. Seeing this, Giussani received permission from his superiors to teach Religion in a public high school. Beginning in 1954, he taught at Liceo Berchet, a high school with a focus on the classics in Milan, where he remained until 1967.

The content of his lessons were the themes that would accompany him – in a lifelong, ever-deepening study – along his entire trajectory as a man and an educator: the religious sense and the reasonableness of faith, the hypothesis and reality of Revelation, the pedagogy Christ uses in revealing Himself, the nature of the Church as the continuity of Christ’s presence in history up to the present. His presence in the school gave new energy to Gioventù Studentesca (GS or “Student Youth” – the name for the activities of Catholic Action in high school) and gave it the contours of a true Movement. So began the history of Communion and Liberation.

The “PerCorso”

Beginning with the 1964-1965 school year, Fr. Giussani taught Introduction to Theology at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, a position that he would hold until 1990. An organic synthesis of what he taught was published in Italian between 1986 and 1992 in the form of the three-volume “PerCorso,” or “itinerary”: The Religious Sense, At the Origin of the Christian Claim and Why the Church. The Religious Sense would have enduring success; it is currently translated into 23 languages and has been presented throughout the world.

In 1968, GS was overtaken by the political upheavals of the time, and many of its members joined the Student Movement, abandoning the Christian life. During that same year, Fr. Giussani laid the groundwork for a recovery of the experience at the origin of the Movement. The name “Communion and Liberation” was adopted the following year.

The Movement Grows

In the early 1970s, Fr. Giussani became directly involved with a group of students at the Catholic University of Milan. Years of great dynamism, they saw the expansion of the Movement into every realm of life: high school, university, in parishes, in factories and in the workplace, often successfully challenging mindsets that were politically or culturally hostile to theirs. Fr. Giussani did not shy away from the risks of such turbulent growth and untiringly called members back to the “true nature” of CL as an experience to mature in faith, continually pointing out the “consequences” of this at the intellectual, organizational and political levels. His was an exercise in paternity found reflected in the annual “équipe” meetings with university students (cfr. Dall’Utopia alla Presenza [From a Utopia to a Presence] and the other books of the series on the équipes).

In 1977, he published Il rischio educativo [The Risk of Education], containing the fruit of his reflections on over 20 years of experience as an educator. It would become one of his most widely read and translated books.

The election of John Paul II in 1978 marked a deepening of the relationship with Karol Wojtyla that Giussani began in Poland in 1971. For a number of years, Fr. Giussani regularly brought groups of young people to visit the Pope at the Vatican or at Castel Gandolfo.

“When we say that faith exalts rationality, we mean that faith corresponds to the fundamental, original needs that all men and women feel in their hearts.”

The World as His Horizon

As the years passed, Giussani’s early intuitions regarding mission and ecumenism continued to develop. Some GS students moved to Brazil as early as the beginning of the 1970s. At the same time, in part through his friendship with Fr. Romano Scalfi and his organization Russia Cristiana (an association formed to raise awareness about the rich tradition of Russian Orthodoxy), his ties to Eastern Europe and the orthodox world multiplied. Over the course of these years, the Movement continued to grow – primarily in Europe, Latin America and the United States – in part in response to the warm encouragement of John Paul II in 1984 to “go into all the world.” A trip to Japan in 1987 opened the door to a deep friendship between Fr. Giussani and Shodo Habukawa, a priest and prominent figure in “Shingon” Buddhism. A special relationship developed with the CL community in Spain, where Giussani periodically made extended visits: he saw the future of the Movement in the deep relationship of affection and shared approach with this community.

Season of Creativity

The beginning of the 1990s brought the appearance of the first signs of the illness that would accompany him for over a decade, increasing in severity up until his death. Many have noted the parallels between the life of Fr. Giussani and that of John Paul II, and the photo of the two of them together in St. Peter’s Square on May 30, 1998, serves as a memorable emblem of this.

It was also during these years Giussani presented a number of his most enduring meditations to the Movement: Riconoscere Cristo [Recognizing Christ], Il Tempo e il Tempio [Time and the Temple], and È, Se Opera [He Is, if He Is At Work], all expressions of an extraordinary season of creativity focused on the themes of the Christian event and the mystery of God. (cfr. Il Tempo e Il Tempio).

The friendship and consonance with Cardinal Ratzinger, Prefect of the Doctrine of the Faith, were solidified, as the Cardinal himself would not hesitate to reveal.

It was an intensely prolific period, despite his advancing illness. Two of the texts that are fundamental in understanding his conception of Christianity were published: Si può vivere così? [Is it Possible to Live This Way?] and Generare tracce nella storia del mondo [Generating Traces in the History of the World]; he began the series “I libri dello spirito cristiano” [Books of the Christian Spirit,] and the collection of classical music “Spirto Gentil”; he entered into dialogue with Jean Guitton at a conference in Madrid and received the International Catholic Culture Prize in Bassano del Grappa. His attendance at large gatherings of the Movement, including spiritual exercises and assemblies, began to diminish, though he often participated by sending video messages.

“Not only did I have no intention of ‘founding’ anything, but I believe that the genius of the Movement that I saw coming to birth lies in having felt the urgency to proclaim the need to return to the elementary aspects of Christianity; that is to say, the passion of the Christian fact as such in its original elements, and nothing more.”

Last Messages

In the spring of 2004, Giussani’s request to Cardinal Antonio Rouco Varela of Madrid for permission for Fr. Julián Carrón to move to Milan to share the responsibility of leading the Movement was granted. In this new millennium, between 2002 and 2004, an extraordinary exchange of letters took place with John Paul II, ending with the letter in which Giussani writes, “Not only did I have no intention of ‘founding’ anything, but I believe that the genius of the Movement that I saw coming to birth lies in having felt the urgency to proclaim the need to return to the elementary aspects of Christianity, that is to say, the passion of the Christian fact as such in its original elements, and nothing more.”

His last message to the Movement was on October 16, 2004, on the occasion of the pilgrimage to Loreto for the 50th anniversary of CL. The letter opens with the words, “Our Lady, it is you who give certainty to our hope! This is the most important phrase in the whole history of the Church; the whole of Christianity is expressed in it.”

On February 22, 2005, he died in his home in Milan. The funeral Mass was celebrated in the Duomo in Milan by then-Cardinal and Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith Joseph Ratzinger, serving as the personal representative of John Paul II. He was buried in the Monumentale Cemetery in Milan. His tomb became the destination for a steady stream of pilgrimages from Italy and around the world.

At the end of the Mass celebrated at the Duomo in Milan on the seventh anniversary of Fr. Giussani’s death, on February 22, 2012, Fr. Carrón announced that he had submitted the request to open the cause for canonization of the priest from Desio. The petition was approved by Cardinal Angelo Scola, Archbishop of Milan.

On May 9, 2024, in the Basilica of St. Ambrogio, the Archbishop of Milan, Mario Delpini, will hold the first public session of the testimonial phase for the cause of beatification and canonization.

-28-giugno-1987.-insieme-a-shodo-habukawa-nel-monastero-del-monte-koya.-(fraternita-di-cl)-b.jpg)