The Beginning of Peace

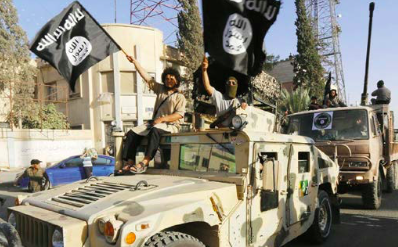

The story of the Tamras family: the night of the attack, the imprisonment, and the faith of three kids together with their father and grandfather while their mother negotiated with one of the militants.Tommy Tamras become the man he is today the night of February 23, 2015, when ISIS came bursting into his village and into his 20-yearold life. He remembers that day down to the minute: the timing, every move, every thought. First came the late-night skirmishes between the ISIS militants and the Kurds, a little before the first rays of dawn flooded the 35 villages nestled in Khabur Valley in northern Syria, where most of the inhabitants are Chaldean or Assyrian Christians.

The second thing he remembers was the sound of Kalashnikovs growing closer and closer to his house. That was when he grabbed his cell phone to call his father. “My parents were in the city, in Al Hasakah, at work. I was at home with my sister Josephine, who’s 23, my brother Charbel, who’s 14, and my 90-year-old grandfather, Michael,” Tommy remembers. He was home on break from the University of Al Hasakah during that period in February. “My dad told me over the phone to get everyone together and run for it. I tried to get out, and I realized that they’d already shot and disabled all the electrical generators.”

In the dim light, he could make out his neighbor running, holding his youngest daughter by the hand. They glanced at each other, and in a half-whisper he said to Tommy, “They’ve come. They’re forcing everyone out to take us away.” Tommy rushed into the house and found only his grandfather. Before he could get out of the house, he had a pistol pointed to his head. The man, his face covered, said, “Come with me or I’ll kill you right here.” They walked a short distance and came to the middle of the village where the other inhabitants, about 90 of them, were crammed into a house. Tommy’s siblings were also there. Josephine was with the women: they, along with the small children, were being separated from the men. After a couple of hours, they transported all of them north into the area controlled by the Islamic State. Waiting there were another 200 people who’d been kidnapped that same night.

The biggest shock for the Tamras children came in the middle of the morning. “It was about 10:00 when Charbel and I saw our father’s car pull up,” Tommy says. “He stepped out and handed himself over. He told the militants, ‘You’ve taken my children and my father. Take me, too.’” At that time, Martin was 48 years old. He’d always worked as a carpenter and then, when the country had been overtaken by crisis, he had gone to work for an organization that helped people who were displaced. That night, he had to make a horrible decision. “I could tell how serious the situation was. My wife Caroline and I wanted to leave immediately. I tried to calm her down. Then, with death in my heart, I left without her seeing me.” He left a piece of paper with a few words written: “Forgive me. I’ve gone with them.”

“When I saw Dad, I felt a burst of strength,” Charbel says. “I understood that I had to look to him.” For example when, a few hours after the kidnapping, the leader announced that they would kill anyone who wouldn’t convert. “My father encouraged everyone saying, ‘It’s a lie. Don’t believe him. Believe that God will help us.’” And that’s exactly what happened.

Olive pits.

Their imprisonment lasted 12 months. Countless times, they feared the end was near, but each scare instead became the beginning of a new peace. Which came back and dominated them even in the most dramatic moments. During those first days, Tommy shut himself off in total isolation. “I was trying to distance myself from all the evil I was seeing. I’d found a few sheets of paper and a blue pen and I spent my time drawing.” Then, the militants came into their room. “They took all of our things, including our rosaries, sacred images, and crosses. And they burned them. That’s what woke me up again.” For the first time, Tommy raised his eyes and realized he couldn’t condemn himself to a prison within their prison. In the face of evil, he could still be free. With his friends, he started collecting olive pits from their lunch and dinner, rubbing them against the walls until they were smooth, and threading them onto pieces of metal taken from the couch cushions to make rosaries. “Prayer became the center of our days. We realized that it kept us human.” Praying together was risky. In the cells, the persecution was constant. “We’d become really good at hiding everything. One day, as I left the room, the rosary slipped out of my pocket. I thought, ‘Okay, I’m in trouble now,’ and I started to pray to Our Lady.” Standing outside the door, he watched the men search the room top to bottom, with his rosary there, in the middle of the bed, but nobody saw it. Tommy’s eyes were full of awe and wonder when he heard one of the men say, “Everything’s in place here. Let’s go to the next room.”

Josephine lived in the camp with all the other women, separated from her family. She was filled with fear and the pain of solitude, but within those dull hours and days of sameness rolling by, something new quickly started to blossom. “There were so many children, all terrified. We started to pray the Rosary, even four times a day, in front of them and with them. Every day, we played games with them and we always found some time to tell a story or two from the Gospel.” The guards surprised her repeatedly. “They told us not to do it anymore, because our prayers were haram, prohibited. I don’t know how, but I found myself standing up to their demands.” By doing this, she showed the full humanity of their gesture. She said to one of them, “But why would it be a sin to pray to God? Don’t you do it as well? So let us pray.” And after that day, the man started to pretend not to hear the Hail Marys that drifted through the walls and under the doors of the tiny chambers where the women were locked away.

Josephine had an idea for Easter. With the help of other women, she managed to collect about 40 eggs. The evening of the vigil, they boiled them in their tea and decorated them. “When they woke up, the children were so joyful they couldn’t contain themselves, and seeing their happy faces, we relived the experience of the Resurrection.”

Before the sheikh.

The most dramatic incident came eight months after their kidnapping. The entire prison camp was moved to Raqqa, the capital of the Islamic State. ISIS had started demanding money from the relatives of the hostages. Now they upped the ante and asked the Assyrian church to pay a ransom to free them. At one point during the negotiations, the militants decided to force their hand with a number of executions. They selected six prisoners, dressed them all in orange, and took them out to the middle of the desert. Martin Tamras was one of them. “I don’t know why they chose me,” he says. “Maybe because, when the sheikh came to our cells and pushed us to convert, I looked him in the eye and tried to disarm every word he said.” For Martin, every gesture and every word comes from a single source: his love for life. His own, that of his children, and even that of his enemies. Those days before the scheduled execution, he did all he could to get his hands on a copy of the Bible, even though everyone thought it was impossible. “I realized that I needed Jesus in order to stand up and face our jailors.” In the end, the “gift” was given to him by the sheikh himself. “He told us, ‘This way I can show you all the contradictions in this book.’ I don’t know if he’ll ever understand that by leaving it in our cell, he had opened up the spring that was the source of our strength.”

The power of this conviction was brought to a decisive level for Martin the day he faced the execution squad. “Before making us line up, they closed us in a little hut. Fear filled all our hearts. In a moment of weakness, one of us said, ‘We have to convert, it’s our only chance.’ That’s when I saw that Christ was all we had left, that the only true chance for salvation was to hold on tightly to Him.” Their guards left some dry bread and water on the ground as a last meal. “I’m not a priest,” Martin says, “but I took them, blessed them, and asked the Lord to remain with us through those signs.” Everyone ate and drank. Then, they placed their lives into the hands of the executioners. “There, on my knees, I thought, ‘If Jesus wants me with Him, I’m ready to follow Him.’” But he felt no bullet. Three bodies fell to the ground: his cousin, his doctor, and a man from another village. “Then, they made us bury the corpses. As I was digging, I thought about how salvation had become a reality in that hour. I had watched those men become martyrs, supported by the certainty that life is something no one can take away from us.”

On the phone.

The execution was filmed, and the video was sent to those who were negotiating the release of the prisoners. Among them was Caroline, Martin’s wife, who works for Caritas in the diocese.

Some weeks before, she had become one of those in contact with the militants. “In the prison camp, Martin had recognized a Syrian man among the leaders whom he knew from before,” Caroline explains. “They managed to speak to each other and Martin won his respect.” As a result, the man called Caroline: he wanted to give her news about her family and offer to negotiate with her. It wasn’t easy. It had taken months for her to put aside her resentment at what they were doing to her family. But as she spoke to this man on the telephone, the last remnants of anger dissolved, along with any strategies. “I just started looking for that ember of humanity that still had to be burning in him under all the ashes. I fanned that ember for months, waiting for his human heart to begin to beat again.”

A sincere dialogue opened up between them. One day, he confided in her, “I see that you have faith. A few days ago, my son was born, but he’s sick. What can I do so that he’ll get better?” She told him, “Pray to God and take care of all the people who are there with you. Seek the good!” Then she sent him a vial of blessed oil from St. Charbel Makhluf, the 19th century Lebanese saint who is venerated in many Eastern Christian communities. He thanked her saying, “You are a good person; if you’d convert, you’d go to paradise.” Caroline persisted: “Any good that you see in me was given to me by Jesus. Therefore, you have to respect it, as I respect your religion.” That was the last exchange they had. Since February 22, 2016, the day the hostages were all released, Caroline has heard nothing more from or about him.

Today, the Tamras family lives in a rented apartment in Al Hasakah. Their village was completely destroyed. No one has been able to go back and live in their home. Tommy and Josephine went back to their studies at the university, Charbel went back to high school, and Martin and Caroline are back at work. Along with their house, they lost everything from their past: pictures, books, clothes, everything. “And our future is also uncertain. Today, things are peaceful, but we don’t know what will happen tomorrow,” Tommy says.

Martin watches his son as he speaks, his gaze both serious and full of compassion and he adds, “In this trial that we’ve been asked to live, we’ve seen our faith grow. If we ask the Lord for help, it’s possible for us to love everything. Every circumstance, and even our enemies. This is our hope for every man and woman in this country.”#MiddleEast