A Life You Can Touch

From Egypt to the Persian Gulf, we met some Christians living in the Middle East, where the recent bomb attack revealed many wounds, but also a communion that is alive, like that which grew out of the Cairo Meeting.The fact that Allah exists makes her relax. "Yes! Relax." In order to be sure that you understand, she takes a deep breath and leans back in her seat in the airplane, amused. "God is this." At first sight, Takwa is not exactly the epitome of relaxation. Since she took her seat, she has been sitting up straight. The veil covers her face all around, and the black gown down to her feet covers the backpack between her legs. But the word "relaxation" is not out of place, because when she speaks of her God and of her religion, you get the impression that, for her, everything has already happened. There is nothing to wait for or to desire, nothing to discover; she only has to do what she is told. Everything has already been said. "Islam governs my relationships and every aspect of my life."

Takwa is flying from Rome to Amman to see her family. She is living and studying in Granada. She tells us how she came to be there, about her life, and about her conversion. Even before, she had always asked herself why she did things. Now, she is sure that God exists and that what He does has a meaning. On the airplane, everyone else is asleep. Beneath the only light burning, she asks about Christianity; she speaks of forgiveness and of her ex-boyfriend. In the end, she shows us a verse of the Koran that she has underlined. She translates it. She says she is "prudent" with those who don't believe in the Prophet, but a moment later she invites me to her home. The fact that I am a Catholic and that she has only just met me isn't important. "It's not often you meet someone that you can speak with profoundly, and I need it."

At the airport, our ways will part, but those eyes highlighted by black eyeliner and full of contradictions have already broken into the chaos of thoughts and questions about life in the Middle East. The bomb attacks in Baghdad and in Alexandria, religious freedom, the face-off between Christians and Muslims … "The possibility of a unity that does not depend on uniformity," that the Pope sees, is important "because man is never expressed fully by culture, but he transcends it, in the constant search of something beyond." This Jordanian Muslim traveling companion reminds me of this. Another reminder comes from the life of Anne, with whom I shared a room in a Maronite parish in Amman, Jordan.

Anne is half Italian and half French, but lives in Qatar. She is a Catholic Christian, a child of Fr. Giussani, married to a practicing Muslim. To hear her speak of her marriage and of her two children, whom they both decided to baptize, seems more like a film than reality. Yet she speaks of a real relationship, lived in a Wahabite country, ultramodern, but still tribal, where the challenge of faith is "being faithful to myself"–and where the bond with her husband helps her to respond to Christ and to her destiny. She convinces me that, in such cases, prejudice, analysis, and the usual categories of coexistence and dialogue don't hold, because they love each other. Only later will you discover that this is not the exception, but the way.

Anne is in Jordan with other friends of the Movement who have come from nearby countries to spend a few days together (it is the first Diaconia of the Middle East–see sidebar). Some of the names have been changed, for security's sake, both because of where they come from (Jordan, Qatar, Egypt, Israel, and Lebanon), and because of the fear due to threats to the lives of Christians. When they met, only two weeks had passed since the New Year bombings which, according to the newspapers, changed that life forever. How was life changed? "Nothing is as it was before," says Said, born and living in Alexandria, a teacher and a father. Today, he is living through the street protests against the Mubarak regime but, before this explosion of popular anger, he saw the annoyance of the Christians at the New Year's Day bombing.

The bombing exposed many hidden wounds: people who have disappeared without any explanation; "religious" murders, like that of his cousin, George; and many episodes that are quickly covered up because the explanation offered is always the same: the murderer was out of his mind. Christians are arrested because they are caught eating during the Ramadan fast; history books censuring Christianity, even in the Catholic school where Said teaches; preaching in the mosques, where on Fridays people are told "not to have anything to do with Christians"; and shops near the churches that close down.

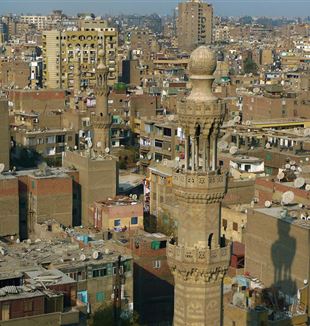

"The aim of Islamizing society has been achieved, and quickly, in education, in the mass media, in commerce…" Boutros Fahim Awad Hanna is the Auxiliary Bishop of Alexandria. He was born in Egypt, and over the past 20 years has seen everything change."The way of dressing and of speaking, television, the continuing fatwas… We are harvesting the fruits of a fundamentalist Islamic current born in the seventies and allowed to develop freely in the country. The outward religious aspect is very strong, but there is no corresponding seriousness in the practice of religion; or, rather, life is not lived at the level of religiosity."

The first reason for this shortcoming is the cultural agony of the Islamic world. "The challenge of modernity is at the root of many episodes of violence," says Fr. Giuseppe Scattolin, a Comboni missionary who teaches in Cairo and is an expert in Islamic mysticism. "The Islamic world has to undergo a profound cultural transformation; it is living a radical tension internally between those who want to open up and those who are closed up in a religious tribalism and don't want the presence of others."

Knocking at the Door

At times, in the face of the blows received by the Christian communities, the immediate temptation is to respond in kind: blood cries out for blood. Then, on the Coptic Christmas, January 7th, two veiled women along with their children knocked on Said's door, carrying flowers. "They wanted to bring Christmas greetings to me and my family and to ask forgiveness for what happened." And there was the Muslim taxi driver, with whom he normally doesn't talk, who told him he was sad for what was happening. "He was upset because he didn't understand. He knows Christians who have never done him any harm; he always goes to a café where the owner, a Christian, switches on the TV so that people can hear the prayers." As the taxi driver lengthened the journey so as to speak more with Said, Said noted that "hope can come from a person you would never have imagined."

While Said is talking, Ibrahim just nods. He, too, is from Alexandria. He lost four relatives and two friends in the bombing. A week later, he and his wife went to the church where the bombing took place. Outside, there was a group of Muslims, in silence. He saw them when he entered the church at ten in the evening, and they were still there at midnight when he came out. "They came up to me and said, 'We are with you. What harms you, harms us; we are together.' I realized that there is a communion that we don't appreciate. It's the same thing I saw at the Cairo Meeting; we are living something hidden, a communion that is the opportunity to free ourselves from prejudices, but only what happens makes us aware of it."

All Quite Different

The Cairo Meeting... Said and the others cannot talk of what they are living now without speaking of the Cairo Meeting. What happened in those two days of meetings between Christians and Muslims at the end of October (see Traces, Vol. 10, no. 10 (2010), p. 8) "is what changed my way of looking at reality, even in the face of the New Year tragedy." Sarah is 25 years old and Egyptian, from Alexandria. She didn't expect anything from the Meeting. "I didn't believe it would be any good, or that people would come; for me success was impossible. I had one idea in my head: that Muslims don't want to be with Christians, period."

Then, something else happened. "It was a miracle," she says. "It was all quite different from what I had thought it would be. We worked together, we were touched by the same things, by the same words. I saw the CL Movement happen there, together with those Muslim kids." Sarah speaks of it with serious, painful joy. The bomb that exploded on New Year's Day is one of those things you have always felt as being far away–"then, all of a sudden, it happens near you, in your life, and you find out that life is a mere breath. And you ask yourself this: what do I want, and whom am I following?" She asks herself this every day. She asks herself this when she has to go to the doctor who has his office near the church that was bombed and she cannot bear to pass by there because the blood is still on the tarmac and on the walls.

There is lot of fear. "But the Cairo Meeting helped me look deeper at reality. Before the bombing, I would have seen only halfway." She found herself telling her friends who wanted revenge that they should forgive. "I felt a new responsibility for my life and theirs. And I cannot say anything to them that is not true for me. This is why I need to do a personal work. I need conversion." This is how a massacre changes life forever.

I Want to be a Shield

In October, preparing for the Cairo Meeting, the Muslim volunteers were "happier and more enthusiastic than us," Said says. "They were the first to open up and this opened us up. I saw that what for me was an illusion had become reality–the words are no longer just words, but life that you can touch. 'Your ways are not My ways'–I saw this realized." He saw that God can join people together in a way that we cannot imagine, and can use a seed, like that of the Cairo Meeting, which seemed so fragile, but was planted in the world. You can see it and touch it.

The day after the Alexandria bombing, amid declarations and the closing acts, the Meeting volunteers organized a concert in Qubbat Al Ghori. On the stage were Christians and Muslims, singing and weeping, as were the people in the audience. Wael Farouq, Vice-President of the Meeting, was invited by the Coptic Pope Shenouda III to a Mass and a meeting with him. Abdel Fattah Hasan, former member of Parliament belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, stated before the television cameras, "If something bad is done to Christians, I want to be a shield with my life."

This is what Said ran to tell his friends after the bombing, "We are inside a great history." This is what makes you feel you are not in a minority–"Half of my anger evaporated at once, when my far-away friends telephoned me." You can see all Christ's words coming true, even those in John, Chapter 16, where he says whoever kills you will think he is doing a service to God. What Jesus said, and that is happening today, "makes us think of our faith," he goes on. "We can discover it, this faith, and live it with others." Rony has his eyes fixed on Said, listening to his words; his face says that, for him, too, it is a step-by-step conquest. He is Lebanese, but that is not important; he feels the bombing as something of his own. "It is the answer of evil to the good that is growing." And he loves this good. "Where is my journey of faith before what has happened?" It is the people around him who recognize it: after the bombing, many people went to see him, upset, simply because he never lets "an encounter, even just a five-minute one, pass without the other knowing that my Lord loves him."

My Children's Destiny

Lives molded by "thoughts and actions that are born of faith…" During his trip to Jerusalem, the Pope said that culture, true culture ("not defined by the limitations of time and place"), comes from here, from lives that resound with God's presence, lives that love. "After Christ had died, it needed the disciples' love to make us understand His death," says Said. There are moments when he thinks that the death of his two brothers was "necessary." Certainly, now, "the disciples' love is needed" to reveal the meaning. "Only in this way can I understand my task, for myself, for my friends, and for everyone."

Anne has tears in her eyes. She says that what she has heard is the hope for her family. The union that happens between her and her husband is a miracle that cannot be built. "It is only because of the presence of an Other that it happens; but the world does not want what is happening to us; it could even refuse our children, the fruit of this union. But now I know that not only do they have a special task, but that their destiny has a place."#MiddleEast