Daryl’s encounters

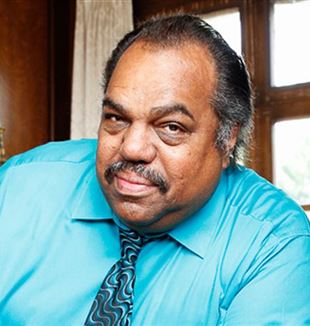

“How can you hate me if you don’t even know me?” This question has stayed with him throughout his life. From September Traces, the story of Daryl Davis, the African American musician who has befriended members of the Ku Klux Klan.Daryl Davis’s agile fingers dance rapidly on the keyboard–he is playing the boogie-woogie, which is both cheerful and frenetic. Davis has had an enviable career. In photo albums, he keeps pictures of himself playing with the greats of American music, including Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and B.B. King. His passion is music, but his name is more associated with his life as an activist who used unconventional methods to fight for the rights of African Americans than with blues progression. In 1998, he wrote the book Klan-destine Relationships: A Black Man’s Odyssey in the Ku Klux Klan. In response to the fury and intolerance of many who protest against discrimination, Davis says that pushback does not lead anywhere. The only solution is through encounter and dialogue, and this is what he has dedicated his life to. For him, conferences, meetings, and debates have all but replaced concerts. This past February, he spoke about his work at the New York Encounter. More recently, following the large Black Lives Matter demonstrations that have taken place in American cities in response to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, he answered questions from a group of students in Communion and Liberation. Today, Davis is even more convinced about the correctness of his approach. He says, “Never in American history have we seen a movement so widespread and heterogeneous. Never have the authorities responded so quickly to condemn the violent behavior of police. We are at a turning point.” However, his argument and his story show that peaceful demonstrations are not enough and that violent demonstrations are even less effective in fighting against the phenomenon of racism in the US.

For Davis, everything began in 1983 at the Silver Dollar Lounge, a local country music bar in Frederick, Maryland. He was the pianist in the main act and was the only black man in the bar. At the end of the show, he was approached by a man who complimented him on his performance, but then added, “I have never seen a black man play better than Jerry Lee Lewis.” Davis replied that Lewis, whom he knew personally, had been influenced by the same black musicians that he had learned from. The man was skeptical, but was intrigued, and invited him to have a drink. They spoke at length, and toward the end, the man admitted that this was the first time in his life that he had sat at a table with a black man. Later, Davis discovered that the man was a member of the Ku Klux Klan, the historical front line of white supremacy. Both realized that their conversation had planted a seed in their lives.

This was the first of Davis’s many encounters with members of the KKK, some of whom, after becoming his friends, decided to distance themselves from the organization. The most significant example is Robert Kelly, the Klan leader in Maryland. Davis first approached him with the excuse of doing an interview for a book, which was coordinated through Kelly’s secretary. He did not expect to meet a black man. There was a series of conversations, and Davis was invited to Klan meetings and night rituals. He listened, took notes, asked questions, and engaged in discussion. Little by little, the stereotypes began to break down.

Davis is not afraid to ask questions, to ask others to give reasons for their positions. This characteristic first manifested itself when he was ten years old. He lived in a white neighborhood and was part of the local Boy Scout troop. One day, during a parade in the city, he realized that someone was directing slurs at him and then throwing rocks at him. This was 1968. At first, he did not believe his parents when they explained to him that the reason he was attacked was his skin color. As a boy, he asked, “How can you hate me if you don’t even know me?” The question became a refrain during his life. “The only answer I got was ‘Some people are just like that.’ That wasn’t good enough. What does that mean? Since then, I have been curious to know the reasons behind racism. But my question still remains unanswered.”

The most recent event, which was covered by CNN and recounted by Davis at the New York Encounter, was the friendship he struck up with Richard Preston, the Imperial Wizard of the KKK in Maryland, who had been arrested in 2017 for shooting a black man during a white supremacy march in Charlottesville, Virginia. Davis decided to pay his bail to free him from jail.

They met at Preston’s house, where Preston explained his justifications for racism, retracing the history of the US from his perspective. “I listened to him and when he was done, I corrected him on a few things that he got wrong. At the end of that conversation, I invited him to my house and we agreed that afterwards we would go together to the African American History Museum in Washington, DC.” Preston came with his fiancé, Stacy Bell, who is also a member of the Klan. Davis showed the picture from that day at the NYE–the two of them are laughing as if they had been friends all their lives.

A few weeks later, Davis was invited to Richard and Stacy’s wedding and he decided to go. The ceremony was in full white supremacist style, with many Confederate flags. The day before the wedding, he received the most surprising request. Stacy’s father was ill and could not come to the wedding. It would be their African American friend who would walk her down the aisle. To those who ask him why he accepted, Daryl says, “Because we are friends." What makes it a friendship is that he does not ask Preston to leave the Klan. For him, he is happy that they share this bond and that it is real. It is a seed that will grow in God’s time.

When the students asked Davis how they can have a dialogue with someone who has contrary views, he answered that first of all you must let the other person be himself or herself. “I don’t respect what they are saying, but I respect their right to say it... If you want to be heard, then you’ve got to let somebody else be heard.” But this is not enough. In the case of controversial topics like racism, attacking the position of the other person is not worth it, explains Davis. “As soon as you begin attacking somebody, the walls come up. I prefer to talk about my position and give my reasons for it. This is the only way that the other person can begin to consider it and reflect on it.”

Being aggressive reveals a fundamental weakness– fear of the other. There is always common ground on which you can begin a dialogue. Davis asked the students, “Do you believe we need better education for kids? Do you believe we need to do more to get drugs off the street? You’re agreeing with a neo-Nazi. You’re agreeing with a Klansperson. And it has nothing to do with race. When you discover that you share common ground, it is easier to see him or her as a person and not as an enemy... You started this far apart but when you find commonalities, you’re beginning to close the gap. By the time you get here [to a friendship], the trivial differences between you such as skin color... begin to matter less and less.”

Read also - Society is changed by those who have been changed already

Davis is not fooling himself about the state of his country. Tensions are growing and far-right groups will keep multiplying. The cause behind this, according to the musician, is that the face of this country has already been transformed and will continue to change. “In a few years, 50 percent of Americans will be non- white. In the following generation, whites will become the minority. This is a threat to the power structure that has existed for four hundred years. This is disconcerting for many people. They are frightened.” It is by preying on this fear that neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups get recruits.

“People have to stop focusing on the symptoms of hate,” concluded Davis. “It is like putting a band-aid on a tumor. To treat the illness, you must go to the root of all of this, which is ignorance... There is a cure for ignorance. The cure is called education... Provide more education and exposure to these people... If you cure the ignorance, there is no fear. If there is no fear, then there is nothing to hate. If there is nothing to hate, then there is nothing to destroy.”