Society is changed by those who have been changed already

The US presidential elections, anti-racial protests, and an increasingly polarized country. What is the contribution of Christians today? A conversation with Stanley Hauerwas and John Zucchi to revisit Fr. Giussani’s "From Utopia to Presence."Faced with the wave of protests that were unleashed by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, many in the US CL community felt the need to engage with the deep challenge that this historic moment poses. Many felt an urgent need to join the protests and show solidarity with those who are suffering racial oppression. Yet others, in the face of political polarization and the continued violence, expressed caution. In a country that has become even more divided by ideological positions (with Biden/Harris supporting racial justice and Trump/Pence defending police and public safety), the community had been pressed to go deeper into the heart of what it has received from Fr. Giussani. What is or could be the manner of our presence in the world in this highly politically charged moment? In what ways can we creatively engage the issues and respond to the obvious wounds that are tearing America apart and to which no one is a stranger?

Many among us have observed how this moment parallels the experience of the movement in Europe in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, as violent protests, fueled by Marxist ideals, rocked the universities. In 1976, in a direct response to the university’s students’ manner of facing these protests, Fr. Giussani spoke to their leaders at Riccione, urging a decisive return to the essentials of the Christian method. He later referred to this key address as a new beginning for the movement.

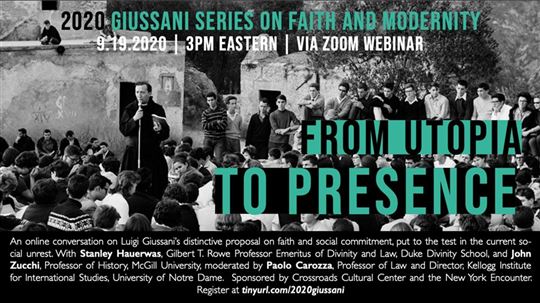

Convinced that this talk, “From Utopia to Presence,” is a precious help for Americans right now, the organizers of the annual New York Encounter teamed up with Crossroads Cultural Center to propose a Zoom webinar to engage Giussani’s statement. The September 19 event brought together Stanley Hauerwas, the Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law at Duke Divinity School and John Zucchi, Professor of History and Classical Studies at McGill University.

In his introduction to the presentation, moderator Professor Paolo Carozza of the University of Notre Dame Law School told the over-800 attendees that we, like the students Giussani addressed, are living in a “time of nervous activism, of polarization and conflict, of projects and utopian ideals.” How, he asked Zucchi and Hauerwas, can the “method of presence” that Giussani urges challenge our perspective? What can it mean for us right now?

Zucchi admitted that he found himself reflecting on the “method of presence” in his initial encounter with the Black Lives Matter movement as he read about their local protest in the newspaper. “My first reaction was ‘Too bad I was not there.’ But then I thought, ‘Why would I have gone?’ The first thing that comes to mind, the modern mentality, is ‘I have to do something.’ Whereas the real question is ‘Why do I do it? With what awareness do I do it?’” Reflecting on that awareness, Zucchi insisted, is key. “We are constantly thinking, ‘What can I do to improve society?’ Is it because I have to do something, is this why I begin the initiative? Or do I simply want to communicate what I have been given or, better still, to give of myself, to share my life—which demands a certain authenticity from me?” “If it is mere activism,” he added, “it can wear itself out or become violent. . . . With ‘presence,’ I can carry out the same initiative, I can be involved in demonstrations or protests even, and yet there is no goal of resolving problems.”

In the same vein, Hauerwas spoke of the “presence” of the physician who says to a dying patient, “Simply because you are ill, I am not going to abandon you.” “That kind of intense human relation is what Giussani is about. We, through Christ, have been called into the world to be present to the agony of the world in the way that we do not use methods that only increase the agony in the name of justice.”

The most powerful example of “presence” he has encountered in this time, Zucchi said, is in the story in an op-ed piece by Gregory Charles, a black entertainer from Quebec. Charles tells how his father, fifteen years after being cruelly denied an apartment because of his race, found himself caring for the very man who had denied him the apartment, now a patient with a painful fracture in the orthopedic ward where he worked. Explaining his choice to care for the man who had been so cruel to him, his father told Charles, “He is in pain and he needs comfort. I will do for him what must be done, and I will do it as well as I can. And I heal a man because that is how we love and how we win, son.” When the man left the hospital, he said to Charles’ father, “Thank you for healing me. And I am not talking about my leg.”

Charles’ father, Zucchi noted, “was one who lived this constant relationship with the one who changed his life. He went to Mass every day and was actually killed by a snowplow coming out of Mass one morning. In front of all these issues that involve racial tensions, he began with the individual, with no project in mind, and one person was changed, converted. Giussani asks us to begin with this level here, not the grand project of constructing a new society, but starting from our own unity from the point where we have changed. What happens afterward is not our business. . . . Society is changed by those who have been changed already."

In this context, Hauerwas suggested that Black Lives Matter responds to a deep need to change society, but in a way that finally does not satisfy. “The Black Lives Matter movement is a gesture toward having some kind of response to the slave-racist character of our lives as Americans in a way that somehow relieves the agony of that. What do you do when you have been a people that receive a history that was so wrong that there is nothing you can do to make it right? How we acknowledge that and know how to go on is one of the great challenges before the American ethos.” “American liberalism,” he said, “is a production of people who believe they should have no story except the story they chose when they had no story. That is what we call ‘freedom.’ The problem with that, of course, is that’s a story they did not choose. It leaves you with a life you are not sure you want. The Black Lives movement is an invitation that finally identifies with something that is unambiguous, that gives the life I like living. But the problem is that you need more than that. It is not immediately apparent, what the more is. Giussani offered the young people moral orientation that produced lives worth living. And that is ‘presence.’”

Zucchi added that “there is something false in utopia because our desire for happiness is infinite and a utopia is always a human construction, with all of its limits.” Both speakers pinpointed clear signs of utopianism in this current moment. Zucchi recognizes it in the “jumping into proposed solutions of our problems without ever getting to the root of the problem in the first place.” Hauerwas sees it in the hubris of the American claim that “we are the greatest nation in the world.”

Are the reduction of the scope of reality and the failure to see our own limits, Carozza wondered, expressed as well in the current university context in “the desire to cancel the realities of history, to characterize everybody in dualist categories of good and evil?”

“What could be more self-righteous than political correctness?” Hauerwas pointed out. “The modern university is in deep trouble. You cannot ask, what is it for? And who does it serve? You have people saying you cannot read Macbeth because there are no good witches or it is derogatory towards women. Some people think you cannot read The Wizard of Oz because it is fantasy.” “The religious right and the left both have claims about what can and cannot be taught in a way that ends up underwriting STEM majors with a loss of the humanities, which serve to form our fundamental perceptions about what is good and true. We are in trouble. We have not been producing people of eloquence and wisdom.”

Similarly, Zucchi sees the many instances of protesters pulling down statues of prominent historical figures in an attempt to “erase history,” as “a pitfall of moralism.” “Having a moralistic position does not require that element of community, that I belong to something else. I can go it alone and stand on my high horse and say that I think I am able to follow a particular code. The others have not followed it. And down comes their statue.”

In the light of these intense cultural challenges, Carozza noted that Giussani’s talk ends with the admission that we cannot “win”—and yet, it is at the same “imbued with Christian hope.” “Victory is already inside us,” Giussani wrote.

Hauerwas concurred. “Non-violence is not an attempt to win, because it has already been won through the cross and resurrection. The notion that we have got to win doesn’t give you a Christ who won.” Zucchi experienced the “victory” when he become friends with those who opposed the Christian position in the euthanasia debates in Canada. “The experience of Christ’s victory becomes clear when I no longer see the distance between Christ and the other, when I want to reach out to the others’ humanity and hope that that same humanity might reach me. ”