Invasion 14: An Original Composition

A new work by Christopher Vath for narrator, violin, cello and piano set in the squalid WWI prison of the Maxence Van Der Meersch novel. Performed Saturday night at the 2017 New York Encounter.Frenzy. Intensity. Dissonance. Energy. Piercing longing. These were the words that sprang immediately to mind with the opening notes of the first musical composition of the Invasion 14 presentation Saturday night. Even before any words were spoken, the audience was swept into a drama of uncertainty, of fear, of passionate need, as the music seemed to be running everywhere, looking frantically for something just out of reach. The piece was entitled “Apocalypse”, and had been chosen to set the stage for this dramatic reading of Maxence Van der Meerch’s novel, Invasion 14, which tells the story of a French village under German occupation during World War I. Chris Vath arranged the presentation, selecting the music to complement the readings. “I asked Fr. Rich, ‘Do you have a story for me?’” he said, and Fr. Rich, having just finished the novel, suggested the story of the priest and the prisoner, which represents just one vignette from the overall work. From there, Vath picked music that would portray the trajectory of the story. “I picked tough music”, he said, both in terms of technical performance and in sound, because the scenes portrayed in the story required this, and allowed the audience to enter into the darkness and tragedy.

Chris Vath had chosen selections from the novel to express the story particularly of a priest, and the fellow prisoners he affected. A collection of musical compositions by a variety of composers were chosen to complement and draw out the themes of the story, and were performed by Chris Vath on piano, Rubin Kodheli on cello, and David Marks on violin.

The performance alternated between the spoken excerpts of the story, and the musical pieces, only at times overlapping. This alternation created a beautiful dialogue between the words and the music, allowing the emotions, the full weight of the words, to be explored, unfolded, and illumined by the particular language that only music can speak. “Daniel had been in Roubaix since 1916…” are the words that open the story, and take us on a journey through the excruciating conditions that Daniel and the other prisoners, held by the Germans, are undergoing. The author gives vivid descriptions of Daniel’s pain, from the terrors of his physical hunger, to the starvation of the presence and consolation of his wife, to the gnawing emptiness of his mind: all of them are described with the imagery of hunger. The music followed the dramatic descriptions, taking us through a sense of unrest, despair, turmoil, and frantic fear in front of the emptiness. It was at the description of his longing for his wife and child that there was a shift to a gentler theme of sadness, of ordered, clarified longing in the music, even amid the dissonance and turmoil. It is the first time that a calmer, more clear embodiment of sorrow is portrayed, as if the memory of a beauty, of a good that is lost. The music captured beautifully the clarity to his desire, to his need, a concreteness that stands in contrast to the previously given description of emptiness and murky nothingness threatening to overcome him.

Hope suddenly breaks into the story with the arrival of the priest to the prison, who establishes a relationship with his guards by his openness and kindness that brings a level of freedom to him and enables him to be in a position to give to his fellow prisoners. The music reflecting this shift of hope expressed the piercing experience of beauty in the midst of pain; a timid excitement, almost playful, like a child anticipating, cautiously, that there could be more, a reason to live again.

The priest begins slowly to fill in the various hungers of his fellow prisoners: from reading to fill their minds, to light and food, to his personal presence. The priest anticipates the needs of his fellow prisoners, by giving to them what he himself would want, and is without. But it is ultimately himself that Daniel begins to receive back when the priest tells him, “Someone must have big plans for you to have sent this much suffering your way”. Daniel is opened up to hope precisely by this radical new gaze on his life that is able to look at the same impossible circumstances, and see the merciful hand of God, to see a purpose, a good, a reality that is “for you”, such that he is even enabled to look at his guards in a new way as a result of the priest’s gift, recognizing that it is possible for one to “accomplish something, bring men back to goodness.”

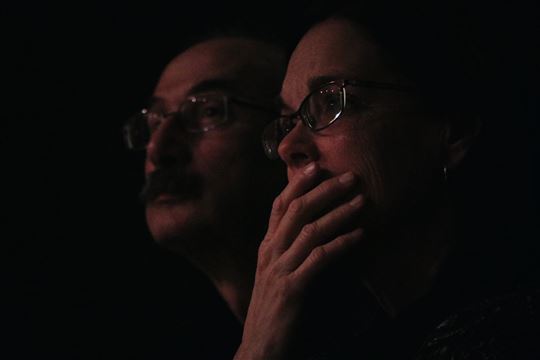

The last two pieces of music reflected a heart wrenching beauty and hope, not without pain and longing, but with a promise of fulfillment that was not present in the order-less frenzy of the opening piece. The performance gave a beautiful, artistic experience of an answer to the Encounter’s theme, and challenged the audience to enter more deeply into the mystery of the gift that reality presents even in the darkest of moments.#NewYorkEncounter