Spurred by the Promise of Happiness

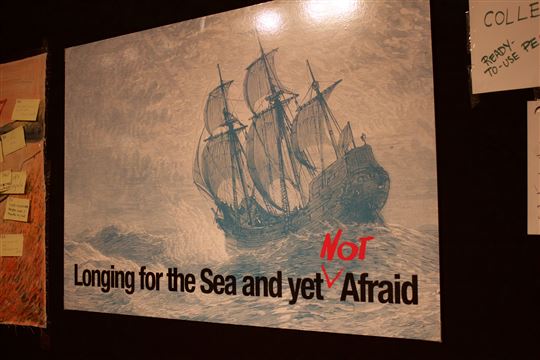

"God goes, belonging to every riven thing he’s made / sing his being simply by being / the thing it is.” Poet Christian Wiman spoke of poetry, faith and recognition at the 2016 New York Encounter opening event.On hearing poet Christian Wiman speak, the word “fearless” is more likely to come to mind when describing him. Against the Masters poem’s incisive diagnosis of our common experience, that is, desire choked by fear, Wiman’s life and words ring out with an inexorable fact: that the diagnosis is not enough.

When Greg Wolfe, editor of the arts and literature journal Image, asked whether the poem sparked anything for him, Wiman paused, carefully considered the question, and replied in his deliberate, steady voice, which carries the ghost of a native West Texan drawl: “In my own life I am shocked by how often I can articulate a psychological dilemma, and how being able to articulate it cannot rescue me from it… we think [that if we] can just put words on it then we will be released from our tensions. But I’ve found this is not true. I think what releases me are remembrances of moments when I was released.”

The quiet intensity of the answer gave credence to Marilynne Robinson’s description of Wiman’s impressive body of work as having “a purifying urgency that is rare in this world.” Wiman’s oeuvre includes nine books of poetry, essays, and translations, and ten years at the helm of the prestigious literary magazine, Poetry.

Wiman, drawing on a phrase of Rabbi Abraham Heschel, stressed the need to be faithful to those moments in which we have had faith. Wiman complemented Master’s poem with a stirring reading of A.R. Ammons’s poem, “The City Limits,” which begins, “When you consider the radiance, that it does not withhold / itself but pours its abundance without selection into every / nook and cranny…” The poem is permeated with the presence of an other, filling and illuminating creation and ripe with a promise so full it transfigures the fear which previously choked desire: “And fear lit by the breadth of such calmly turns to praise.” Wiman described the poem as “a moment of faith, written by a person, incidentally, who professed to have no faith.”

Wiman was careful to describe, in his most recent book of essays, My Bright Abyss, his own return to faith as an assent “to the faith that was latent within me.” In many ways, the transition seemed seamless to Wiman, for he sees present in his work from the beginning “an inchoate longing that I was constantly trying to give form to.” The longing for completion was the same; the language had changed.

In Wiman’s acclaimed 2010 collection, Every Riven Thing, his poem, “From a Window”, concludes with a similar revelation to that of Ammons: “that life is not the life of men. / And that is where the joy came in.” This particular poem was written a few months after Wiman received a diagnosis of incurable cancer, and he writes that it was “one of a handful of poems I wrote after my diagnosis that gave me some sense of purchase and promise: the terrible vagueness of things was dispelled for a moment and I could see where I was standing, and could feel a way forward.”

As Wolfe noted, however, it was not his illness but the experience of falling in love with his wife the previous year that had first moved Wiman to return to religious faith. In My Bright Abyss Wiman describes how he and his wife both found themselves at the dinner table moved to pray together. Why, Wolfe asked, should this experience of falling in love move them both to desire to pray? Wiman did not pause: “We were looking for someone to thank… there are moments when your life seems to overbrim and reality seems more than reality, and yet itself not equal to reality. Everyone I know in those moments want to express gratitude. We had lost the language with which to address God and praying together became a way of trying to do that.”

If falling in love moved Wiman to prayer, his illness made demands on the expression this rediscovered desire for God must take. After a painful and devastating bone marrow transplant, Wiman described feeling an intense desire for “the concrete… palpable particularity… I kept at arms length any notion of Jesus until I got sick… I needed faith to take concrete form. I needed church, I needed people. I needed to know why I needed those things.” While Wiman told us that he stands open before these questions, his certainty of his need for this life continues unwavering. “For anyone who feels their faith to be an unstable thing, the thing that stabilized it [for me was] to see it stable in someone else. To see credible faith enacted in an other.” This movement from the abstract to the concrete has led Wiman to conclude that “the eternal gets played out in our daily lives, in minute atomic ways.”

As time began running out, Wolfe urged Wiman, on behalf of an eager audience, to gift the packed auditorium with some recitations. To hear Wiman recite his poems is to hear a man dance gingerly in the rhythm and play of language (the seed of belief is a “little weedy hardy would-be / greenness / tugged upward / by light”) and also plumb his own experience with unflinching seriousness and an almost fierce tenderness (“Love’s last urgency is earth / and grief is all gravity”). Yet the humility of facing experiences which paradoxically both surpass him and beckon him onward, births a voice of boldness and authority: “God goes, belonging to every riven thing he’s made / sing his being simply by being / the thing it is”.

What seemed to shape all these elements together during his reading were the silences between Wiman’s carefully arranged lines, each break creating a pregnant space in which the poet and listener both wait inside the echoes of the word’s particularity, filled with expectation.#NewYorkEncounter