Antonio Polito: Fear and Presence

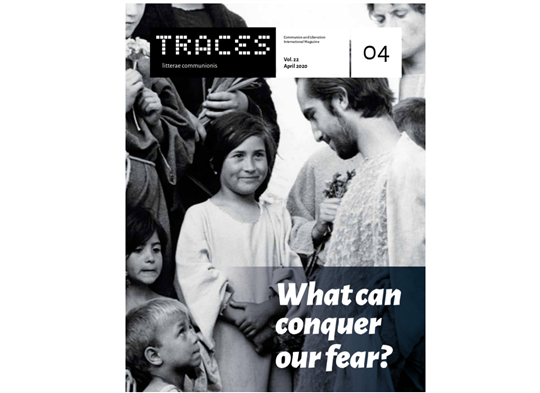

The coronavirus is sending a Western civilization “increasingly indifferent to the very idea of Jesus” into crisis, leaving us at a fork in the road... From April Traces: an interview with Antonio Polito, columnist for Corriere della Sera.“It is a powerful image. And an effective one, because it speaks to an experience we have all had.” When Antonio Polito, a 64-year-old columnist for Corriere della Sera, read the piece by Fr. Julián Carrón released in his newspaper on March 1, a simple but powerful passage struck him: “What conquers a child’s fear? The presence of his mother.”

It may seem strange to see that image as the response to a drama that has upended our lives and the whole world, but it raises a crucial point. Coronavirus has suddenly pushed us into the gravest crisis we have faced in decades. It has revealed the “deep fear that grips us at the depths of our being,” Carrón writes, a fear to which only “a presence” can respond, but “not just any presence. This is why God became Man” and entered human history. The need for this presence is why it is so vital for us to seek out His witnesses, those “presences in whom we see an experience of the victory over fear in action.” In other words, the key, more powerful than a thousand analyses, lies in an experience, a mother and her child. Polito underlines this, saying, “I see the need to have faith in something greater than us that loves us infinitely and therefore protects us, the same need children have. When I encountered the mother/child image in Carrón’s letter, what came to mind was Our Lady of Mercy, the one you see in many paintings, do you know the one? She opens up her mantle and shelters the people.” He, too, has been shut up in his house for days, like (almost) all Italians. “It is a kind of social distancing, but also of family closeness,” he observes, smiling. “For the first time in many years, we are always together.” It is from that perspective, from his living room and the days packed with unexpected discoveries (“Have you ever tried to get Google Classroom to work? It’s infuriating”) and conversations with his children (“They, too, are really struggling with being on lockdown, but they understand the reasons”) that he observes Italy–and the rest of the world–as it grapples with an event that can bring countless truths to light.

What can free us from our fear?

That is one of the most important lessons for us to learn. It’s imperative because this situation with coronavirus goes really deep. It has called into question at least four of the great myths of today’s world, of a Western civilization that has become increasingly indifferent to the very idea of Jesus. And I’m saying this as a secular man, in some sense.

What are these myths?

The first, if you will, is that of the goddess Gaia. The earth, nature. For some, she has become almost an idol, as if she were a divinity in her own right. Many ideologies are derived from this, including that of the most reactionary super-environmentalists who think there are too many of us, that it would be better if man were extinct, that the earth has more rights than we do...I am not talking about a healthy environmentalism, let’s be clear: nature is extremely important and defending it is critical. But, according to its own laws, life fights in every way to survive, even a virus. And we have to face that sensibly. Nature is not God: it is part of creation. The same applies to another myth, equal in scope but opposite in nature: the myth of Science.

That, too, is indispensable, but has its limitations...

Exactly. Modernity lives and breathes the notion that no matter what problem or emergency comes up, Science and Technology will be able to overcome it. We will find the remedy and the problem will be solved. That’s not true. There is no medicine to fight a new virus like this one. We have to start all over again, patiently, for example by looking for a vaccine that might be able to stop it a year from now, but who knows what will have happened in the meantime. Technology cannot do everything. Science is essential, but it is not omnipotent. This may seem obvious, but it is an important lesson for those who worship the goddess Techne.

What are the other myths?

They all go together, to some extent. One is the god Ego, individualism. This situation is demonstrating to us that, in a state of emergency, only certain collective behaviors will yield results. Egotistical attempts constructed on individual interest alone are so ineffective that they actually cause more damage: if I run away from the red zone to go back home, or get together with my friends at a cafe because “only old people are getting sick,” I become part of the problem. The old law that the market is built on– seeking one's own best interest creates well-being for everyone–does not holdup. There are critical realms of life in which it simply does not apply. And connected to that illusion, if you will, is a fourth idol: Chaos. Some of us are convinced that, in the end, things work better if you do not follow the rules. Well, that’s not the case.

Carrón observes that a circumstan-ce like this “reveals what kind of progress we–each of us personally and all of us together–have made on the path of maturity”; we see “the self-awareness we have gained.” What do you see blossoming?

Something important: a feeling of vulnerability. Recognizing this is critical. In the world of our parents and grandparents, an epidemic like this was an almost regular occurrence, and people often died in their thirties. This is not the case today, and so the precariousness of life is something our age tends to censor. In fact, there is even research dedicated to achieving immortality. In the most advanced place in the work of combatting this virus, Silicon Valley in California, the tyrants of Big Tech are investing millions in biotechnology and integrating man and machine. There are already hundreds of frozen corpses, waiting for science to be able to bring them back to life...The dream of immortality is stronger than ever in contemporary society, which considers itself to be the last, definitive civilization, the one that can succeed in liberating humanity from death. For a society that lives in the grips of such hubris, powerful enough to feel supremely sure of itself and in- vincible, discovering fragility is extremely upsetting. This discovery is resulting in terrible trauma, but it is a trauma that may help us.

What does a reminder to seek out the witnesses of a “God who became man, a historical, embodied presence” do for us in such a situation?

I don’t know, but one of the reasons Christianity has spread all over the world is precisely its promise of de- feating death. The warrant for this promise is nothing less than the sacrifice of God Himself. It is the only religion in the world in which God becomes man and passes through death in order to say to man that all of us can rise again. There are historians who contend that one of the reasons for the success–let’s call it that–of the faith was the fact that Christians acted differently during plagues and epidemics: others ran away, but they instead helped the sick, even at the cost of their own lives. This gained everyone’s admiration. “Why do they do it? They must be protected by the Almighty...”

Is the same true today?

The only way to fight death is to hope in the resurrection, and that hope coincides with the figure of Jesus. This is an answer that secularism, unfortunately, has chipped away at over the last few decades, and it has lost some of its strength. By this, I do not mean a reduction in the number of Christians, but rather in the strength of the faith of Christians themselves in the resurrection. Christianity has been reduced to a series of values and precepts that can be shared to a certain extent with a secular society, but its true significance has been totally lost. Yet the prospect of the resurrection is the only way to fight the fear of death, and death itself, at its root. Actually, not only our fear of death, but our daily awareness of our own finite nature as well.

You mean an existential insecurity, what Carrón calls an “incapacity to face the life in front of us.”

Exactly. The fact is that we are the only living things capable of imagining ourselves, of imagining the world after our death, the world that will come after us. This creates a kind of structural insecurity–from birth, we experience a nostalgia for the in nite. The only remedy for this insecurity that has emerged in the Western tradition is faith in Christ, Christ understood as the Ri- sen One, as God who, having become man, died and rose again. This is why we use the word “grace.”

Doesn’t this situation become an opportunity to discover that, deep down, we depend? On other people and perhaps on an Other?

Part and parcel of the crisis of sup- posed invincibility is coming to the awareness that, more than depending on one another, we complete one another. We cannot fight something like this on our own, not only because we feel a need to stick together, but because we are a community. We need solidarity, to see our neighbor doing something good. More than dependence in a secular sense, I would say “interdependence.” In front of something so immense, we need other people. In Christian terms, if you think about it, this is the redemption that mercy brings.

Carrón speaks of this moment as an “opportunity we do not want to miss”...

Yes, and I understand why. I do not know if I would say the same. No one is happy to find himself in such a circumstance; you perceive what is happening as a punishment of some kind. But it certainly is an experience. Something that three or four generations of Europeans have never experienced. A threat like this, so widespread, which has brought on wartime economic conditions so quickly–they have never seen such a thing. It is an exceptional experience at a collective level and unthinkable under normal circumstances. It will surely push us to reflect on our human condition.

Click here to read the April issue of Traces#Coronavirus