Bumping into a Life

A group of university students from North America worked together for a year on an exhibit on Fr. Luigi Giussani. The result was 21 panels showing how his experience continues to shape theirs today through an ongoing companionship.In years past at the New York Encounter, there has been an exhibit on Msgr. Luigi Giussani–a 14-panel exhibit manned by a few volunteers and available to any Encounter attendee curious about the history of Communion and Liberation and its founder. After the 2017 installment, the volunteers reported back to the organizers of the Encounter, and told stories of the beautiful reception the exhibit had received from newcomers with many questions and people already in the Movement who were struck by learning something new. On one occasion, a man told a volunteer, after going through the exhibit, that he understood what his daughter had found in following the university students of CL (CLU).

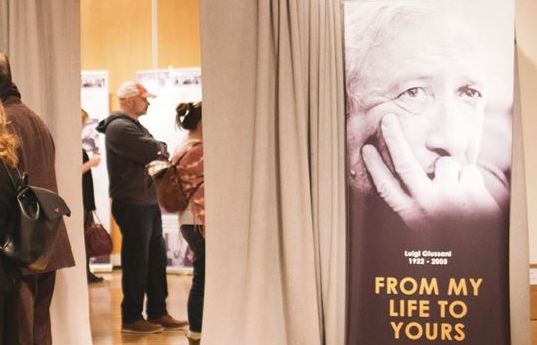

Revitalized interest. Recently, in the CLU in the U.S. and Canada, there has been a renewed desire to understand the history of the Movement. At the vacation and exercises in 2017, the students heard many witnesses from those who first met CL in America in the 1980s and 90s. So when the organizers of the Encounter were considering expanding the Giussani exhibit, many in the CLU were immediately interested. “The work came out of a personal desire to know Fr. Giussani more,” said Fr. Pietro Rossotti, the leader of CLU in North America. Grace, a college student from New York City who has been in the Movement her whole life, described how doing this work revitalized her interest. “Through this work, I’ve become so much more excited because this text is a person.” The work was carried out across North America and emphasized understanding what the life of Fr. Giussani means now for every person involved. Different communities read different works by Fr. Giussani and excerpts from the new biography, The Life of Luigi Giussani, by Alberto Savorana. Each community pursued the themes that struck them, such as charity, mission, or culture, and tried to understand what Giussani proposed, comparing this with their own experience in the CLU. Additionally, many of the students reached out to, became friends with, and interviewed Americans and Canadians who had had the opportunity to meet Giussani. What resulted was a 15-minute video of excerpts from these interviews and 21 beautiful panels about the height of a person ripe with images, stories, and witnesses from the life of Fr. Giussani, the life of the Movement in its beginnings, and the life of the American and Canadian CLU now.

The exhibit began with a panel relating an anecdote about a Cardinal, Fr. Giussani, and his friend Enzo Piccinini. The story is that while Enzo was accompanying Giussani on a visit to the Cardinal of Bologna, Giacomo Biffi, Giussani “rushed to kiss his ring, and Enzo followed suit, but somewhat awkwardly, and with little conviction.” When the Cardinal pointed out this lack of conviction, Giussani responded, “It is true, but if he continues to do it, he will eventually believe in it.”

In bold letters. This particular story resonated with Giulia, a student from Houston, as she was preparing to give tours of the exhibit. “I thought that I’m exactly like Enzo Piccinini. Something happened in my life, and there is a beauty that I perceive by awkwardly following Fr. Giussani and the Movement. Even if I don’t understand it fully, I know for sure that the longing for this beauty that I have been feeling my entire life can find an answer only through this companionship.”

This desire for beauty manifested itself in other places in the exhibit. Another panel addressed a desire to combat “the neglect of the ‘I,’” as Giussani phrased it. In bold letters on the panel, there was this quote from Giussani: “There is no greater inhumanity than working to erase the ‘I.’ The inhumanity of our age is precisely this.” This is an experience known all too well on college campuses. “I learned that another studentwas eating her meals in her room because she hated being alone in the crowded dining hall,” read an excerpt from a recent New York Times article (“Loneliness and the College Experience”). The exhibit went on to highlight how the “I” is truly reborn in an encounter: describing Giussani’s teachings about John and Andrew’s first encounter with Jesus, retelling the story of Giussani’s challenge to a young man to “love the Infinite,” and recounting Giussani’s eagerness to communicate his experience of faith when he first started teaching in a high school. “To bump into something absolutely and deeply natural, because it corresponds to the needs of the heart that nature gave us, is something absolutely exceptional” (Luigi Giussani, Recognizing Christ). Francesca, a history student from Canada, spoke on one of her tours about how she had been struck to learn in her research that Giussani gave up what was a promising career as a theologian to teach high school students.

Javier, from Washington, DC, wrote about his experience of rediscovering the “I” for one of the panels. “I was raised Catholic for the first 17 years of my life and had formed what I believed was a very strong connection with God, but then very suddenly and without much warning, my faith was put to the test. I found myself turning away from God entirely. This period lasted for nearly a year. Needless to say, this was a very bad period. I started to try believing in God again, but it was very difficult and I truly didn’t believe I deserved God’s love anymore. A friend of mine unknowingly flipped my world upside down in the best way possible when she invited me to join her on a retreat. There, I took advantage of the sacrament of reconciliation for the first time since turning away from God, and I got to meet an amazing community of people that I am proudly a member of now. Since joining CLU, I have come to realize just how important it is to resist the desire to take on life all on my own, but instead to overcome my difficulties with the help of my community, through whom I can best engage with Jesus.”

Through a lens. Another panel expressed Giussani’s conception of culture. “Culture is the discovery of the ultimate meaning of things and of life: the Truth.” Understanding art, music, books, history, and current events through this lens is one crucial aspect of the life of the CLU.

One example came from Alex from Toronto, Canada. Posted on one of the panels was an email she wrote to her friends after the terrorist attacks in Paris in 2015, expressing her desire to understand this “ultimate meaning of things”: “Dear Friends, as I am sure everyone has heard, there were terrorist attacks in Paris last night. I would like to propose that we all come together to judge what happened. Why am I proposing this? Because I cannot stay in front of what happened without you. I ask myself, what does studying have to do with the attacks in Paris? How can I study when this just happened? Why should I? What will studying do? Is it just a distraction from what is happening over there? From what could happen here? But also, how can I stay in front of this? How can I not live in fear and sadness for what happened? A friend told me something very interesting when I talked to her yesterday. She said that the only place to start is from the fact that Christ saves my life, chooses me. The only point of hope is starting from the encounter we have had. From this, we can say it is reasonable to hope. Life has meaning because my life has meaning.”

Another section of the exhibit focused on the meaning of charity, with examples from both the past and present. Margaret, from Minnesota, wrote about a conversation with a stranger on her way to the charitable work of singing at a nursing home. A man washing shop windows inquired if she was going off to study, but was surprised to hear her answer. “He was so curious as to why college students would do such a thing on a Saturday morning. I told him that we go every month and sing various kinds of music. I told him that we love to go because we leave so much happier and that we need to be with the people in the nursing home because they help us see the simplicity of life again. We proceeded to have a conversation about how his wife had died and he was afraid of getting old and dying... ‘To hear that you and your friends go to sing at a nursing home makes me less afraid to die– thank you,’ Bruce told me before I said goodbye. I learned something that day: the charitable work does not just begin when our ‘planned activity’ starts, rather is the law of my life–to give myself to others, to give my attention to Bruce, because I desire that he meet what I have met. I am learning that the particular moments of the charitable work are an education to live reality as a constant giving of myself to another person, because it is more beautiful that way, and I am less afraid to die.”

Morning Prayer. One of the pictures on this same panel shows the CLU of Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas, doing their monthly charitable work: visiting a paralyzed young man who can no longer speak, and singing for him. Another part was devoted to Giussani’s understanding of mission. “Only what is great, what is total, what brings everything together can help a man put up with the humiliation of caring for and attention to details.” Mary, from Atchison, wrote something for one of the panels about the necessity she feels to live life as mission. “We always say Morning Prayer in the center of campus together. I ordered many copies of the Book of Hours and the Songbook for our community out of a desire, the desire to engage with my friends in the gestures of the Movement. On Tuesday morning, a priest came to me and said that the last thing he was expecting was to see ten college students chanting the Psalms at 7:30 in the morning. He said, ‘It is clear you have met Christ and now you wake up the rest of campus with your voices.’ I was struck because I saw that Fr. Pietro’s words were true: ‘An exchange of ideas remains abstract until you live them.’ Mission is not what I do. It is who I am.”

Feeling Small. The exhibit also included the words of Giussani on the beggar as the protagonist of history, “The Mystery as mercy remains the last word even on all the awful possibilities of history. Because of this, existence expresses itself, as an ultimate ideal, in beggarliness. The real protagonist of history is the beggar: Christ who begs for man’s heart, and man’s heart that begs for Christ” (Luigi Giussani to John Paul II, May 30, 1998).

On the same panel as this quote, the CLU described its annual pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Good Help–a Marian shrine located in Wisconsin. One testimony from this experience described an encounter with a friend met along the way. “We met Nicole during the pilgrimage; she was one of the parishioners who hosted us. She decided to follow us for part of the pilgrimage. Afterwards, she wrote: ‘We did not know who exactly we were going to be hosting. It turns out that you are a group of inspiring young people. You are my community, you are the community I have been praying for, and you all showed up at my doorstep.’”

Many who attended the exhibit, and there were a very many, were provoked not only by the content but by the tours themselves. Giulia was struck by many of the questions from those she gave tours to. “I had beautiful dialogues. Some of them came back at the end to say goodbye and to thank me. There was a man that had just met the Movement a month before who told me that he wanted to come on the pilgrimage with us this year.” Some of the encounters on the tours were very personal. Teresa, from Atchison, gave one to just a single woman. “She asked me many questions and finally asked me with great intensity: ‘When did you meet Christ? And do you still meet Him?’ As I answered, tears began to fill her eyes. I felt small because instead of me bringing or revealing Him, He had come to me through the eyes of this woman who desired so much. She said that she wishes her students could know what I had just told her, that Christ comes day by day through our lives. She gave me a huge hug at the end, thanking me for reawakening her heart. My heart had also come alive through her!”

Years Later. Emma, from Steubenville, Ohio, had a similar experience. “I was working in the exhibit on Fr. Giussani more awkwardly then Enzo Piccinini before the Cardinal, and I saw a man looking at a panel for a long time. I decided to say hello and ask what he was thinking about. He asked me almost right away if I had read the panel. “Yes,” I said smiling. It was the story of Fr. Giussani’s words to the couple kissing in the garden. He asked me what I thought about it. I hesitated. For me the story was humorous, and I liked seeing Fr. Giussani’s vivacious personality, but I didn’t understand what his response had been. So I asked him what this panel meant to him. He had been standing there awhile. It was clear this story meant something much deeper to him than humor and personality. He said, ‘You know, I’m married. It is hard. I want to love my wife, but yeah, so many times I try instead to possess her. This is where I go. Fr. Giussani is brilliant. He reminds us of the stars.’ From this man, I was given access not just to Fr. Giussani’s personality, but his heart. Even to people he did not know and was not bound to, he spoke words of freedom and love, and now his words were giving these things to this man and to me years later.”

The exhibit included many other stories, pictures, and witnesses. Each was an echo, in its own way, of the words of Giussani quoted on the concluding panel. “To give your life for the work of Another always implies a link between the word ‘Other’ and something historical, something concrete that can be touched, felt, described, photographed, and has a name and surname.”#NewYorkEncounter