He stood among his own

Jesus bursts into the closed room overcoming the apostles' fear: this is how Duccio di Buoninsegna depicts the Risen One. From the "Maestà" of Siena Cathedral, the image on the CL Easter poster.On October 9, 1308, Siena’s Opera del Duomo commissioned Duccio di Buoninsegna to create the altarpiece for the cathedral's high-altar, known as the Maestà. Formerly, the term designated the depiction of Christ enthroned (Maiestas Domini), but in the 13th century the intensification of Marian devotion raised the Madonna and Child to the honours of the royal throne. The contract that the Opera submitted to Duccio was rather binding: the payment was given as a salary and not as a reflection of the value of the work, the materials would be paid directly for by the Opera, and the painter could not take on any other commitments until their final delivery of the altarpiece. These were customary demands for contracts with artists, but here one can hear an echo of the disagreements between the Opera and Giovanni Pisano, the greatest sculptor of the time, who only ten years earlier had suddenly left the façade building site due to alleged delays and defaults. It was better that they protect themselves, as they were about to give form to the beating heart of the cathedral and the city.

Duccio was around 60 years old. Years full of experience and fame, lived in the wake of the Byzantine tradition, but with an ever watchful and receptive eye on the protagonists of his time: first Cimabue, with whom he had a closer and more lasting dialogue, and then Giotto. The latter had recently dismantled scaffolding of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, where he had deployed a visual narrative capable of revolutionizing, not only in painting, the forms of memory and identification with the Christian event. The altarpiece of the Sienese cathedral also included stories of the Virgin and Jesus to accompany the Maestà: Duccio is said to have painted them in the "Sienese" style, introducing into that already personal tradition, all the features adopted from other masters and contexts. This was what commissioners and fellow citizens expected: to recognise their own history and vocation within the altarpiece that was to stand at the centre of the cathedral.

After three years of work, expectations were fully met. On June 9, 1311, the whole of Siena –with the bishop at the head along with the highest government authorities, followed by all the citizens and a host of children in a line – accompanied the great altarpiece from the artist's workshop to the cathedral, passing, of course, through the Campo, where all the shops had their shutters down in devotion. It was a festive devotion, cheered by “trumpeters and shawms and castanets of the Comune.” The civic value of the Maestà was declared in the inscription on the base of the Madonna's throne: “Holy Mother of God, be thou that cause of peace for Siena and, because he painted thee, thus, of life for Duccio.”

Duccio's Maestà, painted on both sides, is unusually large: it is just under five metres in width and height, including the crowning of the pinnacles. The side facing the congregation features the Virgin enthroned with the Christ Child – the Maestà – accompanied by an "imposing and gentle host of angels and saints" (Luciano Bellosi). Framing her, above and below, are episodes from the Virgin's life. The side facing the clergy presents the Gospel narrative, from the Temptations to Pentecost, and develops in a dense sequence of illustrated panels. In the centre, significantly larger, is the Crucifixion. Two centuries after its triumphant ascent to the high-altar, the Maestà gave way to other furnishings and was placed on a wall, again in the cathedral. There followed a history of displacements and cut-downs, which dispersed many panels: some ended up in museums around the world, others are no longer traceable. The main panel and other minor scenes remained in Siena and are now exhibited in the Museo dell'Opera. Among them is The Appearance of Christ behind closed doors.

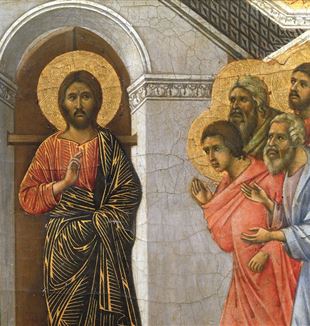

The Appearance occupied the first left pinnacle on the back of the altarpiece. A summit and opening position. Here begins the altarpiece’s last narrative sequence that, along the entire crowning of the altarpiece, holds at its centre the theme of the relationship between Christ and the apostles in the days from the Resurrection to Pentecost. That is, that sequence of events in which the Risen One's presence on earth was inseparably welded with the beginning of the life of the Church. The beginning of this story finds a particular iconic solemnity in the Apparition, of Byzantine heritage. But Duccio nonetheless manages to combine symbolic and narrative registers, so that Mystery and reality come together in an infinity of surprising nuances. According to the Gospel of John, towards the end of the day of the Resurrection, Christ appeared to the apostles in a place – traditionally identified as the Upper Room – kept behind closed doors "for fear of the Jews".

The painting precisely follows the Gospel description: "Jesus came and stood among them." Christ's step is immediately suspended, captured in the slight projection of his right leg, which moves his cloak and foreshortens the support of his feet. The figure stands frontally, wrapped in thick golden highlights traced on the red and blue of his robes, so that the light of the Resurrection shines on the blood and water gushing from Christ's side. The compositional relationship between the Risen One and the closed door behind him is the central axis around which the symbolic and narrative development of the episode develops. It is not the door of just any building, not even that of the cenacle depicted in the previous scenes. It is the door of a temple, an almost triumphal arch, with marble surfaces and refined classical details, which extends at the sides into two foreparts, also with closed doors. Above these are the salients of a wooden roof, the top of which has unfortunately been lost.

Read also - Easter 2024. The Communion and Liberation poster

It is clear, however, that the place of the Apparition was not a closed room, where the apostles had taken refuge out of a fear that we can liken to that "sense of defeat" of which Pope Francis speaks. It is a new building, which leaves behind those closed doors, which weigh down like "the stone of the tombs in which we often imprison our hope.” It is the new temple that opens wide before us "for Christ is risen and has changed the direction of history." Two centuries earlier, Abbot Suger of Saint Denis had written that the door of the cathedral is a symbol of Christ, because Christ is the true door: Christus ianua vera. Duccio reiterates the same concept by transfiguring a place barred by fear into a temple that projects itself onto the new course of history. Christ "resurrecting invades history irresistibly, attracting people to Himself, whose unity constitutes His Body, the mysterious Body, or people of God" (Fr. Giussani).

It is the beginning of the Church. And this is what Duccio describes in moving from the symbolic register of the background architecture to the narrative register of the figures in the foreground. Jesus comes "among" his own who all tend towards him, irresistibly attracted by his unexpected presence. It is a presence that in the divine splendour of the Resurrection continues to be incredibly human. Jesus does not keep his gaze fixed ahead in a transcendent dimension. He immediately seeks out his disciples by turning his eyes to the group to his left, where he recognises John, the beloved young man. Even his body seems to move slightly in the same direction, freeing itself from the rigid centrality of the door behind him. From these small signals, the apostles recognize that it is Him, alive, with His body still marked by the wounds of the cross.

This group remains more distant, as if suspended by the intensity of the gaze that challenges them. The apostles on the left, with Peter mirroring John, seem less in awe – the Master is looking at the others – and more resolute in approaching Christ. We can imagine the disorder and confusion that, only moments before, dominated this group of men dominated by fear and despair. By appearing to them, Christ brought back order, clarity and a renewed surprising attraction. Duccio depicts this by animating the iconic presence of the Risen One at the centre of the apostolic group with discreet nods to his vibrant humanity, against the backdrop of the new temple. A figure of that peace that Christ announces to his own and that Siena asks of his Maestà.