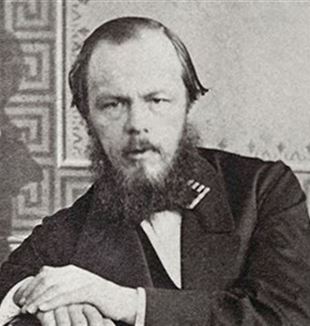

My friend Dostoyevsky

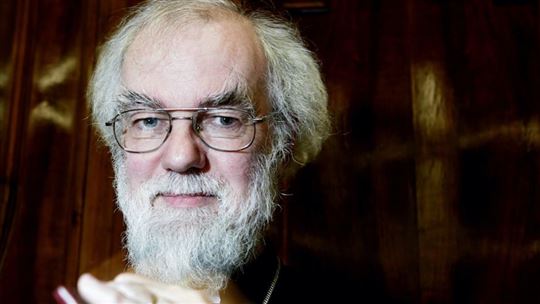

On the 200th anniversary of the birth of Dostoyevsky, former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams speaks of how the Russian genius has changed his way of seeing.November 11 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Fëdor Michajlovič Dostoevskij, one of the most impressive and mysterious figures in world literature. The Gambler, Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, Demons, The Brothers Karamazov. Who else can boast of such a rosary of masterpieces? Those who love him do so with unconditional love, which is deep and full of gratitude. Among them is Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury (2003-2013), and internationally renowned theologian, literary critic, writer and poet. He is considered one of the most brilliant Anglophone scholars and published a book on Dostoyevsky in 2008: Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction. Rowan's longstanding friendship with Fyodor Mikhailovich has grown and has been nurtured by an abiding interest in Russian Orthodox theology, to which he dedicated his doctoral thesis. The title of his latest book is Looking East in Winter (2021), which sounds like a line from an autobiographical poem. We asked him how this great artist has changed his life and his way of perceiving the world. And why Dostoyevsky is worth reading – or reading again – today.

Can you tell us about your friendship with Dostoyevsky?

It is a great gift to be able to talk about this writer who has for me been such a beacon, such a point of orientation for so many years. I first came across Dostoyevsky when I was a teenager, mostly through extracts in other people's books. I was fascinated because here was a writer of obvious contemporary depth, courage, realism, who was also a deeply rooted Orthodox Christian. However, I did not get around to reading The Brothers Karamazov until I was a student. I still have the edition that I read when I was twenty, and one or two little notes in it which tell me something about what I was hearing then. One of the notes is a quotation I had heard from a priest at that time: “The twentieth century can still understand the language of God because it is the language of Calvary.”

Why did you note that down?

I wrote that because it was part of what I was hearing as I read the novel. The language of God is the language of human extremity, lostness, and suffering. We meet God not just in moments of ecstasy and fulfilment; we meet God in moments of bewilderment and loss, and the recognition of our own inner turmoil and sometimes our own inner emptiness. I was reading that in Karamazov, I was sensing it in myself and in my world. The years that followed were really my first encounter with the great novels, portraits of a lost and confused society, and the way in which deeply destructive forces can insinuate there. Thus these are the novels I have continued to go back to. I then extended my reading, looking at the earlier works, especially Notes from Underground, and A Writer’s Diary – that very mixed and rather ambiguous collection of writings. But I returned to him, as you say, as a friend, a very challenging, critical, difficult, embarrassing friend, but nonetheless a deep relation.

What do you admire about Dostoevsky’s writing?

He has an extraordinary gift for producing some deeply memorable details in a scene. It may be a detail about someone's personal appearance, or it may be a detail about the room people are in. He will almost sum up the terror or the atrocity of a scene, not by a huge amount of detail but by one small, apparently neutral detail.

For example?

The terrible, terrible account in Devils of Stavrogin's seduction of a little girl. Stavrogin watches the girl hanging herself through a crack in the door, and Stavrogin suddenly recalls watching a small red spider at a window. This somehow crystallizes the atrocity of the scene as nothing else could. Thus he has that gift of the apparently random detail. I wish I could do that when I write. Another example is in Crime and Punishment: the murderer Raskolnikov is someone whose heart is wrenched by the sight of an animal suffering. These little details which give a depth of physicality to his imagination, are important. But a perhaps even more interesting aspect is that brought out in one of the great twentieth-century studies of him by Mikhail Bakhtin. Bakhtin was the first to underline the fact that Dostoyevsky works dialogically and polyphonically, bringing different voices into play. Dostoevsky allows the contrary voice as much freedom as he can. He liked to say that he could make a better case for atheism than most atheists could. That deep imaginative readiness to step into the mind and heart of another seems to me at the center of Dostoevsky's achievement and it is something which I have always thought profoundly valuable. In a way it is profoundly Christian: as Christians we believe that God redeems not by talking us into silence, but by inhabiting our own human voice. Saint Augustine says that Christ speaks with the voice of a sinful and lost humanity; He takes that to Himself, He enters in imaginatively to the experience of a humanity that is very different from His own serene and unbroken contemplation of the Father. Dostoevsky is always trying to get over that barrier into the heart of the other. He says what he wants to say, therefore, by letting those voices speak to each other; he does not start with a tight agenda that he then follows through, but he tries to inhabit the voice of the other.

You are a priest, theologian, poet, and writer. What has Dostoyevsky’s art offered to your life?

As a priest I have always thought it is essential to have at least something of that willingness to be imaginatively in the experience of another; not to address from outside, but to try and accompany in your heart and your prayer the person who is asking for pastoral assistance and counsel. This attitude has been deep in my heart as a priest. Even as a theologian, I would say that I like to do my theology in conversation; I like to have another voice to engage with. This is sometimes a voice that I am deeply sympathetic with, but is also sometimes a voice I am not so sympathetic with. However, it is another voice which draws out unexpected things from my own mind.

What about as a writer?

I think here of the Anglican poet George Herbert. Most people would say he is about as different from Dostoyevsky as could be, and yet Herbert too likes to give voice. He likes his poetry to be a letting free of some aspects of difficulty, struggle and darkness. As a priest he does not quite know what to do with these, but he has to give them voice, he has to put them there. Thus, as a poet, I feel that I can voice feelings, perceptions which are not necessarily where I want to stay, but they need to be out there to be seen and understood.

Are there any scenes from these novels that are particularly rooted in your heart?

I think here of that scene at the opening of the The Brothers Karamazov, his final novel, where the elder Zosima – the saintly spiritual counsellor – meeting the Karamazov family, bows down to the ground before Mitya, the eldest son, who is a drunken dissolute soldier. Zosima gives him the utmost veneration because he sees in him, prophetically, the suffering which will break him and remake him, and which will actually, eventually, make him the moral center, the moral climax of the story. That image of the saintly old man bowing down before the soldier is very powerful. Then, later in the novel, when Zosima has died and Alyosha, the youngest of the brothers, is keeping vigil by his body and has this extraordinary vision of the starets’ radiant face. And the saint tells him that on the far side of everything there is a joy and an abundance that cannot be imagined, and that the world is shining with the glory of God, and that we are all welcome at the wedding feast. The title of the chapter, “Cana of Galilee”, is an evocation of that.

You like the more “mystical” Dostoyevsky.

I actually love those moments in Devils where Dostoevsky's darkest imagination comes through and what some people have called his “cinematic imagination’, that is his ability to give you a powerful visual scene. For example, late in the novel, when Pyotr, who is one of the arch villains in the book, has persuaded one of his co-conspirators to commit suicide and the other man has gone into the neighbouring room with a gun. Pyotr waits for the sound of the shot and nothing comes; he goes into the room next to him with the candle in his hand. It is pitch dark and he cannot see anyone in the room. Then, at last, he turns around slowly with a candle and there is the other man pressed against the wall, his eyes staring. Pyotr drops the candle in shock and the other man picks up Pyotr's hand and bites his finger to the bone. It is a cinematic moment of extraordinary force and it is part of the evocation of the terrifying, irrational abyss of evil and destruction that that book opens up. It is an unforgettable scene for me. It is one of the most shocking things that Dostoevsky writes.

What can Dostoyevsky teach people living now in what is a new era, where the old categories of understanding the world are no longer valid? What can he offer to our post-modern world, marked by the pandemic?

One of course is that Dostoyevsky believes that while suffering is not something which God inflicts by way of punishment, suffering is always a doorway into learning, above all something about the fragility that we all share with one another. We are not protected as human beings and so we need to protect one another. We are not immortal, we are not secure against pain and failure. It is important, therefore, not to not idolize success and control, but to think always of how we deepen our care and protection for one another. I think that is basic in him and of course it rests on his deep Christian conviction about creation, and Incarnation. The second thing is the theme which surfaces more than once in Karamazov in Zosima's own reflections about his life and in Mitya’s discovery later in the book: we are responsible and are answerable for one another. That is sometimes caricatured as if Dostoyevsky were just saying “well, we are all guilty.” It is not that, but we are all answerable. The state of the world we are in is something for which we have responsibility; it is something for which, as Dostoyevsky would say, we have ‘unlimited responsibility’.

What do you mean by this?

This does not mean that we try to take responsibility for everything and everyone, but that, wherever we are, there will be a call for responsibility which we cannot decide in advance. We do not know where it is going to come from, but wherever we are, there is always a moment where God may come in and say: “I hold you answerable for this situation.” This is our world. We belong to it and we are responsible for this condition. We share the frailty all around us and so our task is protection, care, and the risk that goes with that.

Read also - Syria: When the 'I' flourishes

What novel would you recommend to those who wish to approach this author for the first time?

I would say to those who are afraid of Dostoevsky that what is often forgotten by British readers, and many other readers I suspect, is that he is a great comic writer. We do not think of him as a comedian because he deals with horror and tragedy. But he is, in fact, a great satirist and his portraits of various types of secular and religious life – for example, the extraordinary figure of Father Ferapont in The Brothers Karamazov, or the self-important chattering of the liberal intellectuals in Devils – are funny. And they are meant to be funny. They are very sharp and very comical so not to be forgotten. But if I were trying to introduce somebody to Dostoevsky for the first time, I would probably send them to Crime and Punishment. It is not where I started, but it is perhaps the most accessible novel. It is a story of a troubled young man living feverishly inside his head to the extent that his inner fantasies lead him to a terrible crime and he has to discover what he is he has done and its ramifications. He is surrounded by grotesque and again comical and tragic figures. It has impetus, it has energy. Some of the later novels will take longer to get into, but that is quite a good start.

And to those who have already read Dostoevsky, but who wish to rediscover him?

I would recommend Devils. Although not as finally profound a novel as Karamazov, it has a depth of relentless analysis of our own self-deceiving, self-serving habits: the way in which an intellectual class can be corrupted and trivialized, the way in which revolutionary fervour and longing for justice can become an excuse for violence, the way in which deeply sinister forces enter into this and create a kind of vacuum that sucks others in. It is a very sobering novel but one that in an age of post-truth and nihilism, and so forth, we should read and ponder.