The church and the end of life. The bet on humanity

A doctor is provoked by the Samaritanus bonus, the letter of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. "It is not a list of bioethical norms, but a proposal to freedom".On Tuesday, September 22, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith published the Samaritanus bonus, a letter on the care of persons in the critical and terminal phases of life. As always the Church, when she officially expresses herself on a subject that concerns man, does not propose a list of bioethical norms, but offers an anthropology: a conception of man from which bioethical choices are also made. Again this time, the Magisterium aims high: it bets on the person and proposes a surprising human stature, especially in a historical context like today’s, characterized by an exasperated individualism that borders on narcissism, which ends up generating desperate loneliness.

For this reason, rather than dwelling on a precise analysis of the individual passages, I believe that the reader must first confront themselves with the experience of humanity to which the Samaritanus bonus invites us. It is a matter of verifying the correspondence between what is proposed there and what they live every day, what their heart desires for their loved ones and also their own suffering. Thus, they will be able to recognize the direction towards which this document invites us to orient the timid and fragile steps of our freedom. Freedom which, as Cervantes has his Don Quixote say, "is one of the most precious gifts that heaven ever gave to man."

For this reason, while reading the letter, I recalled my 40 years’ experience as a transplant doctor, my time as a volunteer in a hospice and my insights on the “end of life” issue. As a doctor, so many times (this is our daily job) I have had to decide when to stop treatments, when to continue to insist, deciding with the patient in difficult and challenging situations, when to try everything in intensive care, when to learn from mistakes... I recalled the moments when I met, after some time, the children raised by patients we had saved by running risks. Or when I had to face family members after the death of a loved one whom I had accompanied until the end with palliative care therapies. And I realized, again, that the whole of humanity is always at stake in the care relationship, not just medical expertise or bioethics.

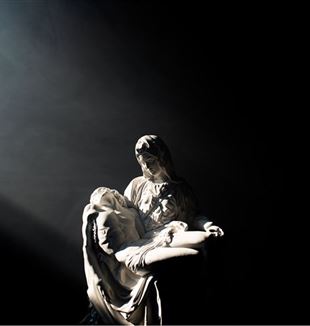

And in recent years, as a volunteer in a hospice for palliative care, I have been able to realize, day after day, that what is needed is not a debate about the end of life, but a presence. To complement the indispensable expertise of doctors in palliative care, it is necessary (and is an integral part of palliative medicine which is also recognized by law) by all, volunteers and professionals, a humble and faithful presence. People who know how to be there and be, sometimes in silence, sometimes sharing with those suffering the dramatic question of why, and the "why me?", looking together for an answer. Thus, I was able to realize that one never accompanies death, but is always at the side of those who suffer to live until their last breath. One always lives (and not only at the end, but every day) for something worth knowing and loving.

Read also – Society is changed by those who have been changed already

The current pandemic, at first, awakened the most essential questions in all of us. But over time, fatigue risks burying them rather than providing an opportunity for more comprehensive care. Today, recovery seems to be an arduous task. For all of us, it is even more evident that in order to live now, in this instant, with consciousness and intensity, it must be worthwhile, you have to be able to smile at something, to want to know and love something and someone, to be amazed by the present moment no matter how tiring or painful it may be. This is the condition and the challenge to be able to lower the sails to go to another port: to perceive the fulfillment of life.

This is the human task of the caregiver: to put their entire humanity into play, even to question the mysterious meaning of what is happening. Without evading the drama.

The text of the letter is full of important consequences and clarifications (and we are grateful for the Church’s clarity in such an easily confused and relativistic world), but we must look at everything from this loyal conception of the human being and from what the heart is made for. We need a path, accompanied by the freedom of each of us, in order to move from simple self-determination, which is the initial momentum of freedom, to a free decision that takes into account all factors. A position worthy of the greatness of man, that can fascinate our children, because it makes life an adventure of fulfillment, and worthy of being lived even with all the difficulties and inevitable fragilities.

* Vice President of Medicina e Persona Association