Cor ad cor loquitur Part I: Newman’s first conversion

For the occasion of the canonisation of John Henry Newman on 13th October, we re-propose extracts from the Newman exhibition, which developed Pope Benedict XVI's reading of Newman's life as a threefold journey of conversion. A journey for us all.Just nine years after his beatification, on October 13, in Rome, Pope Francis will complete the canonization process of John Henry Newman, the great nineteenth century English convert. For this occasion, we re-propose extracts from the catalogue of an exhibition, that was exhibited at the Rimini Meeting, the London and New York Encounters, and other locations in UK, US, Sweden and Italy. The exhibition responded to Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to Great Britain in 2010 for Newman’s beatification. In particular, the exhibition followed and developed Benedict’s reading of Newman’s life as a threefold journey of conversion, from which it emerges that conscience was the driving force of Newman’s journey towards the certainty of truth: ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem (‘out of shadows and illusions into truth’). We retrace this journey, in three stages, as an occasion to get to know the first English Saint of the modern age.

Part 1: The Conversion to the Living God

“The first [is the] conversion to faith in the living God. Until that moment, Newman thought like the average men of his time and indeed like the average men of today, who do not simply exclude the existence of God, but consider it as something uncertain, something with no essential role to play in their lives. What appeared genuinely real to him, as to the men of his and our day, is the empirical, matter that can be grasped. […] In his conversion, Newman recognized that it is exactly the other way round: that God and the soul, man’s spiritual identity, constitute what is genuinely real, what counts. These are much more real than objects that can be grasped. This conversion was a Copernican revolution.”

(Benedict XVI)

Catholicism in England

From the time Christianity took root on its shores, England was a profoundly Catholic country, giving birth to saints and great men and women of faith. England remained a Roman Catholic country until her official separation under the reign of Henry VIII, who, in 1534, issued the Act of Supremacy. This denied the Pope’s authority over the English church, made Henry the Supreme Head of the Church, and dissolved English monasteries and religious orders. The rupture was politically, rather than theologically, driven. The Church of England, however, was characterised from the very beginning by a variety of theological positions, its unifying and most characteristic feature being the rejection of the authority of the Pope.

In the years following the English Reformation, hundreds of recusant Catholics underwent martyrdom, including Saints Thomas More and John Fisher. Henry was succeeded by his protestant son, Edward, and later his staunch Catholic daughter, Mary, who, however, was unable to fully restore the Catholic Church in England. She was succeeded by Elizabeth I, who cemented the break with Rome and was excommunicated in 1570. Subsequently, the celebration of Mass was made illegal, priests were liable to imprisonment and execution, and catholic civil rights were severely curtailed.

The break with Rome had a huge impact on England’s subsequent history. The most important political events of the following years were connected, to a greater or lesser extent, with the religious problem. Religious tensions between a court with ‘Papist’ elements and a Parliament with Puritan sympathies were among the major factors behind the English Civil War (1642–1651), which led to the establishment of Oliver Cromwell’s strongly anti-Catholic regime. The ‘Glorious revolution’ of 1688, which led to the expulsion of the king and the installation of a new constitutional monarchy, was triggered by James I’s Catholic sympathies and his clear intention to work towards the restoration of the Church of England to the Catholic fold.

The situation of Catholics gradually ameliorated, however, during Newman’s lifetime (1801-1890). The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 allowed Catholics, subject to certain conditions, some civil rights on a par with their Church of England counterparts, including equal (albeit restricted) voting rights and the right to hold most public offices. However, Catholics remained highly unpopular in Newman’s England. They were regarded as spies and conspirators, at the beck and call of a corrupt foreign power, aiming to lay its hands on England’s people and wealth. They were accused of sectarianism and the Church of Rome was ridiculed as a corrupt and irrational cradle of superstition.

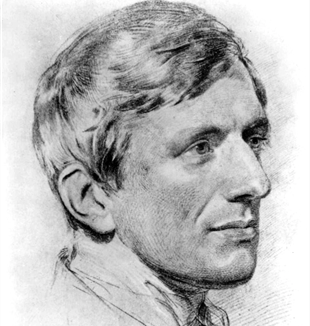

Newman as a boy

Newman was born on 21st February 1801, in the City of London. His father was an English banker and his mother a descendent of French Huguenot refugees. The first child of six, he had two brothers and three sisters. Newman was a strong-willed and very bright child. At boarding school, he excelled at academic work, acted in Latin plays, won prizes for speeches, edited periodicals and loved playing the violin. He was also, however, a very sensitive and naturally shy person, with a romantic or mystical side.

Newman was brought up within a typical Anglican middle-class family. Newman later referred to Anglicanism as “the national religion of England” or “Bible Religion”, which, for many, implied little more than a formal adherence to Christianity. The reading of the Bible had a major impact on Newman. He considered the Bible “the best book of mediation which can be because it is divine. This is why we see such multitudes in France and Italy giving up religion altogether. They have not impressed upon their hearts the life of our Lord and Saviour as given us in the Evangelists. They believe merely with the intellect not with the heart.” (Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman)

Faith in the living God

Newman had lived a happy and tranquil life at home and at boarding school in Ealing. In 1816, however, huge upheaval touched the Newman family family due to the financial crisis, from which they lost their wealth and status. During this unsettled period, Newman fell ill. Newman later noted that he had three serious illnesses in his life and that each illness coincided with a moment of conversion. He described this illness as the “first keen, terrible one, when I was a boy of 15, and it made me a Christian”. (Autobiographical Writings)

It was at this point, at the age of 15, that Newman experienced a profound conversion. This was the conversion to a ‘dogma’, that is to the knowledge of something as true and certain. Left alone at school, sick, and with his family and the security he had known in ruins, Newman was forced to experience the mutability of reality and the solitude of man. At the same time, however, he recognised, in the depth of his human experience, evidence of the presence of Someone else and of an original companionship:

“I believed that the inward conversion of which I was conscious (...), would last into the next life, and that I was elected to eternal glory. (...) I believe that it had some influence on my opinions, (...) in isolating me from the objects which surrounded me, in confirming me in my mistrust of the reality of material phenomena, and making me rest in the thought of two and two only absolute and luminously self-evident beings, myself and my Creator”. (Apologia pro Vita Sua)

A fundamental and real change of life happened in that moment, which deeply effected Newman’s life and which led him to believe that he was called to a celibate vocation.

The imprint of Evangelicalism

Newman’s conversion was not solely the fruit of a personal intuition. Newman experienced God in a particular context as the Christ revealed by the Bible and described by his teachers. During his illness at school, Newman was befriended by one of the masters, Revd Walter Mayers, who was a recent convert to the Evangelical Revival of the time. He recommended some books for Newman to read. Newman became exposed to writers such as Thomas Scott, a famous Evangelical commentator on the Bible, and Joseph Milner, who introduced Newman to the Church Fathers- they would be a key influence on the later development of his thought. The Evangelical Revival was a movement which was influenced by the teachings of Calvin and Luther. The Evangelicals believed that Christianity should be taught through the Bible alone, not through a tradition, and that salvation comes from “faith alone”. This signified that when a person accepts the saving acts of Christ they are converted and they experience a second birth, through which they become predestined to eternal life and cannot fall away (the doctrine of ‘final perseverance’). The Evangelicals divided, therefore, Christians into two: those who had been truly converted and the nominal, unconverted, Christians. This brought the Evangelicals into conflict with the mainstream Anglican Church, which taught that baptism was the act which regenerated the person.

Although recognising the importance of Evangelicalism in his conversion, Newman came to recognise that there was something in the Evangelical doctrines which led him to detach himself from the world. Later, in some of his sermons, Newman would emphasise that the very sincerity of the Evangelicals and their preoccupation with the act of faith tended to lead to over introspection, “They who would make self instead of the Maker the great object of their contemplation will naturally exalt themselves.” (Sermon, Self Contemplation)

Faith as an act of realism

A personal relationship with God had primacy in Newman’s life, and was based on conscience. Newman’s first conversion is essentially an act of realism in which he responds to the evidence of the presence of God, the absolute and luminously self-evident being. The words of Newman’s fictional protagonist, Callista, encapsulate Newman’s own certain recognition of God’s presence, through the voice of his conscience:

“Well I feel that God within my heart. I feel myself in His presence. He says to me, ‘Do this: don’t do that.’ You may tell me that this dictate is a mere law of my nature, as is to joy or to grieve. I cannot understand this. No, it is the echo of a person speaking to me. Nothing shall persuade me that it does not ultimately proceed from a person external to me. It carries with it its proof of its divine origin. My nature feels towards it as towards a person. An echo implies a voice; a voice a speaker. That speaker I love and I fear.” (Callista)

According to Newman, the existence of God is not something that one can demonstrate or argue about with other people, but is an evidence which everyone is called to recognise with and in his own conscience. Everyone is, therefore, called to recognise, within his or her own conscience, the existence of God. Newman said that, in his own case, he became more certain of God than the fact that he had hands or feet- the existence of his conscience and of God were paradoxically realities more real, that is, than reality itself.

Conscience is also, for Newman, the place where God reveals His presence and His will. Newman’s whole life may be seen, indeed, as a journey of obedience to conscience, a path of obedience to that voice, “The one thing, which is all in all to us, is to live in Christ’s presence, to hear His voice, to see His countenance.” (Parochial and Plain Sermons)

Certain of his deep relationship with God, in 1817, Newman moved to Oxford, to study at Trinity College.

#FrGiussani