The Sisters of Syria

In a country wounded by conflict, 6 nuns have made their home on a hill to testify to the "source of peace." We went to see their life, from their Morning Prayer to their handcraft, to learn how it is possible to look at the other "with the eyes of God.""Our Lady, source of peace." The expression is carved in Arabic characters on the great wooden cross planted at the top of the hill of 'Azeir, in Syria, not far from the Lebanese border. From here, one's gaze embraces a breathtaking panorama, from the mountain rising over the river that marks the border between the two countries, to the sea. In between lies a green valley dotted with villages, all inhabited by Muslims, except for two villages with a Christian majority. From here it seems impossible that only a few miles away blood is being shed: the protests against the government, the repression of the regime, the hundreds of victims… You think, and you are struck even more by those words on the cross, which give to the name of the Cistercian Trappist monastery nestled on the hill, where five Italian nuns from the mother house in Valserena in the province of Pisa, a Belgian, and the French chaplain have been living for a few months. A Trappist monastery in a Muslim country? A crazy idea? "It was born after the 1996 massacre of seven of our fellow Trappists of Tibhirine, Algeria," recounts Sister Marta, the superior. "That fact left an indelible mark in our hearts and challenged us to ask ourselves how it is possible to look at Islam with the eyes of God. The patrimony the monks left us, stronger than death, is the testimony of an existence totally offered to God and to the people who surrounded them, Muslims and Christians, something made possible only by their adherence to Christ as the one source of our existence."

The small chapter house conserves two "inheritances" from the experience of the Tibhirine monks (portrayed admirably in the film Of Gods and Men): the chalice and paten they used, donated to the community. They are the sign of a fraternity that continues to live within the mystical body of the Church.

As in all Trappist monasteries, the day at 'Azeir begins well before sunrise. They wake at 3:30, recite Morning Prayer at 4:00 and Lauds at 6:00, have silent prayer in the chapel where the first rays of sun filter in, then Mass and a gathering in the chapter room. "Ora et labora," says the rule written by Saint Benedict. During the day, to the rhythm of seven moments of prayer, the sisters dedicate themselves to ordinary maintenance activities of the community–kitchen, pantry, and laundry–and some handcraft and agricultural work. For the moment, they are making small objects (little plaster statues and rosaries) but they have plans for a studio for artistic glasswork, which is highly regarded in Syria and could open useful market opportunities for maintaining the community. In the land surrounding the monastery, they dedicate themselves to caring for the olive groves, setting up an orchard, and cultivating the vegetable and the flower gardens. "Not only to obtain what is needed for our table, but also to offer to those who come to visit us a place of beauty that fosters prayer and meditation," explains Sister Marta. In fact, part of the future monastery will host a guesthouse for welcoming visitors and pilgrims, who even in these early months are not lacking.

Few Words are Needed

They come from Italy, but not exclusively. Inhabitants of nearby villages come by as well, curious and fascinated by a community of women totally consecrated to God. "And unexpected things happen. Our small experience of faith reawakens the religious sense of the people who live here, reawakens their ultimate questions about existence–above all, in the young people who want to know who we are and why we live together. Few words are needed to explain, because our answer lies entirely in the testimony to the friendship with Jesus lived in this place."

In the hopes of a prayer that can truly be shared with the people there, one of the challenges to face is how to progressively adapt the monastic Liturgy to Arabic language and culture. This demands work on the texts that is challenging not only because of linguistic differences but also because of the difficulty in rendering certain concepts that find no correspondence in Arabic. The canonical forms have to be respected, and adequate terms must be found that not only express Benedictine spirituality and the Cistercian tradition, but also are comprehensible to the people. Translation of the texts is accompanied by composition of music using Arabic scales. Sister Marita, the director of this work of "inculturation" of the Liturgy, does not minimize the difficulties, but is fairly satisfied. "Even if the translation isn't perfect, the people who participate in our functions are steeped in religiosity and understand what we are trying to express. They tell us, 'Don't worry about perfection. Your prayer enters our hearts.'"

The Benedictine charism has ancient roots in this area. In the middle ages, when Great Syria also comprised Lebanon and Palestine, there were eleven Cistercian monasteries, all subsequently destroyed by the Muslim invasion. At the end of the 1800s, because of the anticlerical laws passed in France that threatened the contemplative life, some monasteries created places to host the expelled French monks. In 1882, the Akbès Trappist monastery was founded north of Aleppo; here, Charles de Foucauld lived.

A Relative Freedom

Today, there is no trace of the monastery because of the Turkish persecution of the last century. Currently, the 'Azeir monastery is the only one in Syria that follows the Benedictine rule, and its foundation is a small confirmation of the freedom of expression enjoyed by Christians in the country. This is a relative freedom, which for example does not include the possibility of converting from Islam to another religious faith, or the possibility for a non-Muslim man to marry a Muslim woman, unless he converts to Islam. But certainly the condition of Christians in this country is much easier than that in the rest of the Middle East, thanks to the particular form of secularism guaranteed by President Bashar Assad, who, since 2000, has pursued the policy of his father Hafez: an a-confessional option (Islam is not the state religion), iron control of society, and containment of fundamentalism, to which is added a relative freedom of action granted to the religious minorities, including the Christian and Alawite minorities. The earthquake that has shaken the Arab world in these months has also involved Syria, theatre of protests and clashes with hundreds of deaths. In order to avoid an epilogue similar to that of Tunisia and Egypt, Assad has promised more freedom and reforms in the political sphere. Will this suffice?

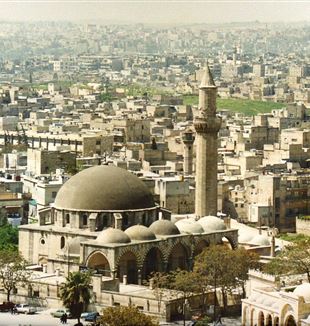

This inter-religious co-existence is the product of a centuries-old tradition and is seen also in the construction of the monastery and the surrounding buildings, still underway. The construction site director is a Syriac Orthodox engineer whose right-hand man is Muslim and whose workers belong to both communities. "The people are hospitable; we're helped by many people, and during this period many simple and unexpected friendships have been formed with many Muslims," recounts Sister Marita, from Milan, who in the 1970s was the volcanic secretary of Italian Student Youth (GS) and in 1973 donned the white garment of the Trappist novitiates at Valserena. Together with Sister Marta, she was one of the pioneers of the project of a new foundation in a predominantly Muslim environment, which was achieved in 2005 when four of them settled in an apartment in Aleppo, where they began community life and study of Arabic. They moved from here to the hill of 'Azeir, and were joined by two other sisters.

Encountering God's Mercy

Marita recounts some of the things that have happened to her that testify to the public regard for this little community. A man asked her to pray for his wife to be able to have a child. A widow, during a visit to the tomb of Zachariah in the Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo, implored Sister Marita's blessing on a daughter affected by an incurable illness. And one day, while she was returning by bus from Mass, a veiled woman with whom she had formed a friendship approached her and handed her a note, and said, "I beg you, bring this prayer of mine to the feet of Our Lady; pray that she may see my pain and have mercy on me." The woman had been renounced by her husband, and asked the Virgin's help to enable her to see the children the court had taken from her. Recounting the episode, Marita is still moved, "because we all need to experience God's mercy. Every day, in monastery life, is the day of the encounter with this mercy."

At eight in the evening, when the moon watches over the quiet of 'Azeir, the last prayer of the community is the Salve Regina sung in front of the icon of the Virgin Mary, illuminated by a votive lamp. From the hearts of Marita and her sisters, the supplication of the veiled woman rises to heaven and is entrusted to our Intercessor, the mother of He who can do everything. The seed planted by the monks of Tibhirine in Algeria has germinated in the soil of Syria. The blood of the martyrs has borne fruit.#MiddleEast