Encountering Our Wounds

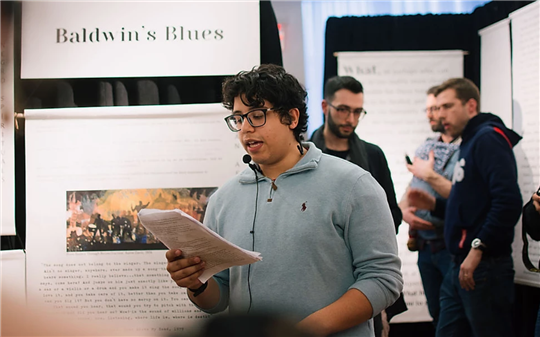

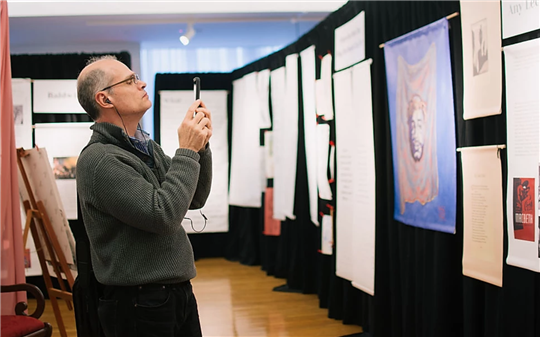

Jaisy's work on the Baldwin Exhibit for the New York Encounter helps her confront her own wounds at the "level of the heart."Come and see. Giussani tells us that Christ’s words to Andrew and John belong to “the Christian formula, the Christian method” (Generating Traces, 5 ). We discover an invitation that waits on our freedom to enter into deeper intimacy with Christ and with others. Such was my experience when I first met Rose and she told me about a group of young Catholics were working on an exhibit about James Baldwin for the New York Encounter. While I had come across this famous African American artist during my education, I was intrigued by the idea that a Catholic movement saw value in his work for their own spiritual formation.

A few weeks later, I was sitting in a coffeeshop, sifting through the initial documents that Rose had sent to our core team. Not only did the attachments include Baldwin’s article “Nothing Personal,” which Fr. José had brought with him to Seattle during his previous visit, but also the proposal for the exhibit itself. As I read the proposal, I was moved by these words:

There is a temptation, when facing past trauma, to ignore or downplay its effect on our present. As much as we may tell ourselves “it’s in the past,” such events continue to shape our day to day lives, self-perception, and relationships with others. On the other hand, there is an equal temptation to seek out or try to construct a solution that will permanently eradicate the suffering inflicted by this trauma, treating it as if it were merely a broken piece of machinery...According to American novelist and essayist James Baldwin, none of these responses get to the root of the problem…The trajectory of racism in the US is the result of people alienated from who they are as beings created for relationship…The only remedy to this evil is an encounter that can reawaken our own personhood. It is those who take the risk of allowing themselves to be loved who can begin to discover their own need and to respect that same need in their neighbor.

These words also brought to mind my experiences in Central Minnesota. Because of an academic fellowship I had received in 2017-2018, I was able to work on my dissertation at an institute located in a fairly homogenous town. It was not uncommon to see flyers for the local state university’s “White Students Union” posted at the local gas station. When I read the Charlottesville slogan (“you will not replace us”) at the bottom of these posters, I wondered who they were talking about.

One Sunday, I went to Mass and found myself sitting in the back. As I turned to give the sign of peace to those sitting behind me, I held my hand up to a tall blonde woman. She looked at my hand held in mid-air, looked me in the eyes, looked back at my brown hand, and gave peace to the person on my left and on my right. I was stunned. I turned back around and wondered what had just happened. As I made my way to the altar to receive the Eucharist, I wondered about the purpose of the “sign of peace” during the liturgy. When I knelt in prayer after receiving the sacrament, I let silent tears express a truth that my mind could not yet put into words.

In that moment, not only had my humanity been rejected, but her humanity had been diminished as well. In the presence of our Eucharistic Lord, the Body of Christ had been wounded. I shared this incident with a few friends and realized that the experience was far more common than I realized, occurring in states as disparate as Minnesota and Massachusetts, Washington and Texas. The color line that W.E.B. Dubois so famously named in 1903 not only cuts across US society, but also across our Eucharistic table, dividing us from one another and revealing our lack of concrete human communion.

As our core team read and discussed a number of Baldwin’s works over a five-month period, I loved how we kept returning to questions concerning the meaning of relationality for our humanity in general and our identities as American Catholics in particular. While it is often more comfortable to talk in generalities about the human condition, I was impressed by how we struggled with what it meant to be Catholic within the white-black racial binary that is part of our inheritance as US Americans.

Reading and discussing Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son helped me to make sense of my year in Minnesota. Baldwin recalls a year he spent in New Jersey without the safe buffer of family or friends to protect him from racial hostility. With society continuously rejecting him at work, bars, diners, and bowling alleys, he wrestled with the temptation to internalize bitterness. At nineteen years of age, he understood that he had lost a certain innocence about human nature because he could never fully be carefree again. He would have to remain vigilant, never quite sure if he could be himself in the presence of racial difference or trust the other to see his full humanity.

Yet, he also did not want to become like his stepfather, who had internalized this oppression from an entire lifetime of racial discrimination. In recognizing both the temptation towards bitterness and the desire to remain free from it, Baldwin ultimately suggests two ideas that must be held in constant tension. First, he must accept the reality of racism that has been given to him – “injustice is commonplace” (Notes of a Native Son, 604.) It is a reality that he cannot escape and one with which he must face without delusion.

Second, and equally powerful, however, is the idea that he must constantly fight this injustice in society. This fight, however, begins with the heart. In every moment, he must pay attention to what is going on within. He must free himself from the internalization of despair that comes with the feeling of constant social rejection. He must also resist letting any form of hatred take root. Only in this manner can he work for racial justice with love, inviting others to examine their wounded hearts as well.

Therefore, it is at the level of the heart—not the law—that we encounter the significance of our racial wounds. While Andrew and John recognized an exceptional presence that magnetized them at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry, Thomas recognized his broken humanity in the presence of Christ’s glorified wounds. The word made flesh became wounded flesh to reveal humanity’s persistent capacity for brother to turn against brother. The resurrection is not simply the victory of life over death, but the possibility of new life, of redeemed relationships, that start from the wounds that divide us. Through these wounds we discover our own need, recognize that same need in others, and discover a path of mutual healing.

My experience of this mutuality with my friends as we wrestled with the presence of racism in our church and society gave me hope for our exhibit, “His Seeing Caused Me to Begin to See": Looking at Race and Reality with James Baldwin. May this encounter with our racial wounds awaken us to how our hearts yearn for full recognition and healing in the midst of racial difference.

Jaisy, Seattle, USA#NewYorkEncounter