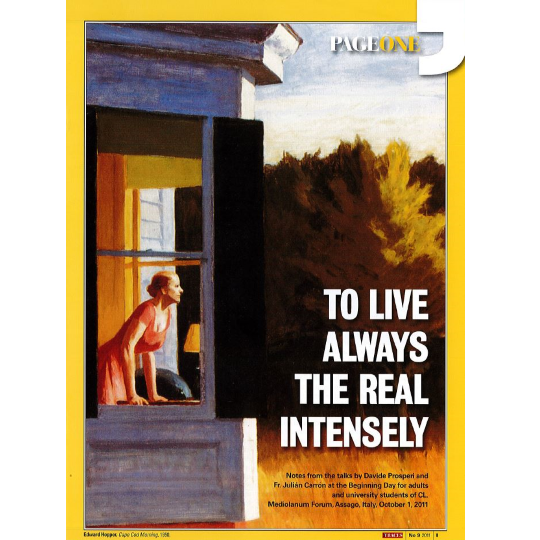

To Live Always the Real Intensity

Page One. Notes from the talks by Davide Prosperi and Fr. Julián Carrón at the Beginning Day for adults and university students of CL.Mediolanum Forum, Assago, Italy.

JULIÁN CARRÓN

Every beginning always carries an expectation. The more we recognize the nature of our expectation, the more we are aware that, in the final analysis, we cannot satisfy it ourselves. Thus, a person’s expectant awaiting becomes prayer, entreaty to the Only One who can truly respond to the scope of our expectation. Therefore, seeing this expectation vibrate in us, let us begin this gesture entreating the Spirit, the Only One able to respond to it.

Come Holy Spirit

DAVIDE PROSPERI

Let’s ask ourselves what meaning there is in our gathering here (those of us present in Milan and all the others in videoconference throughout Italy and abroad) to begin again together this year. The answer is that today, more than ever, we need it. We need to remind each other of the reasons why it is worthwhile to begin again, because we are immersed in a great confusion–social and political, but, above all, a great crisis of the economy and of employment, which seriously endangers the hope of a people. So we are here to tell each other why it is worthwhile to begin again.

The Pope, speaking to the German Parliament last week during his journey in Germany, stated in no uncertain terms the radical question of what it means today to stay before the urgent need of the good of a people: “The windows must be flung open again, we must see the wide world, the sky and the earth once more and learn to make proper use of all this.” (Benedict XVI, Address During the Visit to the Bundestag, Berlin, September 22, 2011). But how is this achieved? How do we gain entrance into the vastness, the whole? How can reason find its greatness without slipping into the irrational?

Last January 26th, presenting The Religious Sense, Fr. Carrón challenged the entire Movement in the year to come to examine the religious sense as verification of the faith. What does it mean to assert that faith lived as judgment on reality is capable of calling forth a full humanity, a reason that resists the assaults of our times, dominated, as the Pope said, by a positivist conception?

This hypothesis was immediately tested during the administrative elections in Italy last spring. And even before that, we were provoked by the flyer entitled, “The Forces that Change History Are the Same as Those that Change Man’s Heart.” Initially, some interpreted it as if something were missing, as if there were a fear of taking a position one way or the other, settling for the reasons of an ultimate position. But it was good that this happened, because it forced us to ask ourselves in a way that was not superficial how much the reasons given were decisive for challenging the world. In fact, we had to examine this (and we certainly did not spare ourselves); we wanted to verify whether the reasons for what we defend, which is not a party, but an experience, “what we hold dearest,” held up. We had to come to an understanding of whether the criteria for looking at things born of our experience were sufficient for taking an original position in front of everyone, first of all for us to be able to live that circumstance fully. Or, on the contrary, whether it was necessary to add something else, a different criterion, a different strategy. But if we had added another criterion (let’s say, a “political” criterion, or at least a “more political” one), at a certain point we would have had to choose between one or the other, because, sooner or later, one criterion has to prevail.

So then the question is: Can the Christian experience be sufficient for determining a holistic position and a judgment on reality, or not? We chose to take this risk. And we saw the outcome at the Meeting, where the irreducibility of our position on politics, like that on everything else, was evident for everyone. After the Meeting, even some secular newspapers, though they did not fully understand where this position came from, had to admit, as Michele Smargiassi did in the August 26th issue of La Repubblica, “Perhaps we need to definitively set aside the question revived annually: ‘Who is CL with?’ CL, as always, is with CL” (“Noi, il popolo di Dio” [“We, the People of God”], La Repubblica, August 26, 2011, p. 37). And we are grateful for this. This irreducibility is not strategic, but is born of a judgment on what we are, and this is what makes us free, free and thus also authoritative. Paolo Franchi, a columnist for Corriere della Sera, wrote in ilsussidiario.net on August 29th, “The Meeting has a long, and by now consolidated tradition of openness, self-confidence.... In a season that seems marked by a war of everyone against everyone, as ferocious as it is unproductive, at the center of the Meeting of Rimini there was the search for things that can and must be done together without anyone having to compromise their own soul, or rather, trying to act in such a way that each person can identify and bring to bear from her own history and culture the best, least transient, and most life-filled part.” (“I, a relativist, will explain to you why I was wrong not to go to Rimini,” ilsussidiario.net, August 29, 2011). And that’s not us talking.

This year, the Meeting took a new step. In the situation of total uncertainty in which everyone, truly everyone, does nothing more than complain (not even one new judgment of hope is heard in circulation), many expected to find in the Meeting the same confusion, the same uncertainty as in the world, maybe looking out of the corner of their eyes to see what power we would seize upon. Because this is the only response one can expect outside a conception like the one we are describing. Instead, those who expected this were blown away, because they saw a judgment that was different, an experience of certainty not determined by the circumstances, be they positive or negative, but the fruit of an original position toward reality. It was seen on many occasions: a new idea of ecumenism, in which a mysterious friendship with people of every creed was born of the acknowledgment that experience seen (let’s not forget that in October 2010 there was the first Meeting of Cairo) is an educational point for everyone. The Rector of the Egyptian Al-Azar University, for example, asked Savorana if he could send some of his university students to Italy to learn about the experience from which the Meeting is born. The philosophers Costantino Esposito and Fabrice Hadjadj showed how the Christian experience responds to the drama of modern thought. And again, think of the meeting on “United Italy, the History of a People on a Journey,” with Giuliano Amato, Marta Cartabia, and Maria Bocci. Or again, consider the reaction of Sergio Marchionne, who returned to the Meeting twice this year and said on television: “I’m interested in the quality of the people who are here. These are true people, people who act. It’s the simplicity of doing. In a country that talks a great deal, these are people who act. It’s a beautiful place to come to” (interview with TgMeeting, August 24, 2011). We saw all these young people, working in the parking lots under the sun, in the kitchens, at the exhibits, at the anniversary exhibit on the 150 years of Italian subsidiarity... These are all kids who have expectations for the future, who see the world in which they are, and yet have a great desire to build, because there is a living experience that is more positive than all the negativity that they hear around them. And we have to look there. In effect, this is the wish President Napolitano expressed when, inaugurating the Meeting, he said, “Bring, in times of uncertainty, your yearning for certainty.” Our task is not to make everyone else think like us, but to work so this yearning for certainty becomes contagious.

Recently, reacting to these facts, Carrón told us, “When are these things a presence that arouses curiosity? When they make the presence of an inexplicable reality emerge in the real: the Mystery. We become interesting when an overflow emerges in reality, because this is what truly attracts.” The Mystery as present reality, even though it is immeasurable, or rather, precisely because of this surplus compared to our measure, fulfills, realizes us, brings to fulfillment the relationship of reason with reality.

Let me tell you about something that happened to me this summer that clarified what we are saying. During a hike in the mountains, there was a very exposed point; a section of the crest had given way and left a hole of little more than a foot and a half that opened out to a void. Along the path there were an adult and two young boys. At a certain point the adult passed and the first boy with him, while the second stopped cold. Initially, I guessed that it was for psychological reasons, some insecurity that the first boy, maybe bolder, did not have. But then I discovered that the first was the son of the adult who passed across, while the other was a friend. That cleared the issue for me. For the second boy, the only reality was that hole that opened out to a void, just “the problem” that had to be overcome, and he did not know if he would have the strength, so he was blocked there. Instead, for the first boy, the reality was the hole and his father, his father who was there with him and who had passed, who had already passed, both things together. There is an affection, a Presence that dominates reality: if reason does not recognize this Presence within reality, reality is reduced and reason is blocked.

Thus, a free reason, capable of staying before reality, is an affective reason. What is the source of this certainty that we all saw in Rimini, that was seen and acknowledged even by those who are far from our experience? Evidently, it is not a matter of self-confidence, like some kind of self-sufficiency we believe we have. It is precisely the opposite: certainty is an “affective” bond with truth, and this, only this, can make us free from any power. So then, if what we most need for living (on the same level as the air we breathe) is a reason capable of recognizing reality in all its profundity, we ask you: Where does a reason like this come from, and how can it be reached?

JULIÁN CARRÓN

1. “Fix as presence the present things”

A reason capable of recognizing reality in all its profundity is born of and is realized in the Christian event. Through the power of the Christian event, reason fulfills its nature of openness before the very unveiling of God. One understands why Fr. Giussani says that “the whole problem of intelligence is there” in the episode of John and Andrew (L. Giussani, Is It Possible to Live This Way? Vol. 2: Hope, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008, p. 105). For this reason, last January 26th, presenting The Religious Sense, we began with the reminder, “The heart of our proposal is… the announcement of an event that happened, that surprises people in the same way the angel’s announcement two thousand years ago in Bethlehem surprised the poor shepherds. An event that happens, before whatever consideration of religious or non-religious person” (L. Giussani, Un avvenimento di vita, cioè una storia [An Event of Life, That Is, a History], Il Sabato, Rome/Milan, 1993, p. 38). What shows that it has entered our life? The fact that “this event”–says Fr. Giussani–“resurrects or empowers the elementary sense of dependence and the complex of original ‘evidences’ that we call ‘the religious sense’” (Ibid.).

This is the reason the Christian event makes man man, that is, more capable of living according to his original “evidences”, more capable of being struck by reality, of living reality according to its truth, because he is capable of using reason according to its true nature of openness to the totality of reality. Only a “reason that is open to the language of being” (Benedict XVI, Address During the Visit to the Bundestag, Berlin, September 22, 2011), as the Pope just said in Germany, can reach reality without remaining prisoner of interpretations that only add uncertainty to uncertainty, as we see today on all levels.

For this reason, we, who participate in this event in the Christian community, should discover in our experience that we are “vulnerable” before the being of things, more capable of being struck, of being amazed, because it is in the relationship with reality, before one’s wife or children, one’s colleagues or the circumstances, the sun or the stars, that we do the verification of faith. If it is true that every person is struck before reality, each of us should be more facilitated in this by the fact of being reawakened by the Christian encounter, so that reality speaks to us more, surprises us more.

But we all know that often this is not the case. Once again, Giussani comes to our aid in identifying the kernel of the problem. Addressing the priests of the Studium Christi in 1995, he said, “The root of the question is the constitutive factor of what exists, and the most important word for indicating the most important factor of what exists is the word presence. But we are not used to seeing as presence a present leaf, a present flower, a present person; we are not used to fixing as presence the present things. We are superficial in this” (Milan, February 1, 1995). And he says this to us, to us who have already encountered Christ and have had our “I” reawakened by this encounter. Therefore, all of us can immediately verify and judge just how much Giussani is right: just observe what happened today, if you were surprised at least an instant by the presence of the things present.

Not coming to a realization of the things present as presence does not mean denying them. Let’s be clear, we can accept them and acknowledge them–Fr. Giussani continues to insist–and even so take them for granted. He is perfectly right. “We are not used to fixing as presence the present things,” from reality, to our husband or wife, to ourselves. What must Fr. Giussani have seen in us, years ago, observing our reaction to his letter to the Fraternity (June 23, 2003), dedicated to the theme of Being, to the point of saying, “I had to discover in these days that Being does not vibrate in anyone!”? Benedict XVI identified the consequence of this position saying that most people, including Christians, take God for granted. (cf. Benedict XVI, Meeting with Representatives of the German Evangelical Church Council in the Chapter Hall of the Augustinian Convent, Erfurt, September 23, 2011).

In its simplicity, this letter from a young university student in Rome expresses the challenge well:

“Last November, I had an accident that left me bedridden for over three months. It was terribly difficult. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t do any activity, nothing, not even study, because the painkillers I was taking kept me from any activity that demanded a minimum of concentration. Three months in bed, still, immobile. I remember, however, that a couple of months after I began walking again, looking at some photos of me in bed with my friends around me, I went to my mother and blurted out: ‘Look what a beautiful photo! Anyway, it was really a beautiful period!’ Looking back, I can say that notwithstanding the immense difficulty of staying still in bed, and the craving to get back on my feet soon, there was something that didn’t make me unhappy; in fact, deep down I was glad in the midst of the difficulty.

“There were two reasons for this. First, in the midst of all the pain, I always felt supported, in a free and gratuitous way, by the faces of my friends, who tirelessly dedicated themselves to me, and by my parents, who always told me to offer the difficulty and pain. I became aware of a total dedication to me–total and detailed. The second reason is that things, even the smallest, were no longer taken for granted. I was surprised by a plate of pasta that was a bit more elaborate than usual, by the companionship I saw around me, by the fact that before going to bed my sisters put the bedpan for the night close to me, without my asking. The climax was one morning, while an ambulance brought me to the hospital for some doctor’s appointments, and I was amazed to see the sky again. I already knew that the sky existed, but finally I realized that it existed, that it was there. [When a person realizes for once in life, he understands how many times for him the sky was not something present.] I didn’t do anything. I couldn’t do anything. And yet, in all the pain, in all the restlessness, I was not unhappy. Everything was taken for the value it had; nothing was taken for granted anymore. Acknowledging the value of things made me glad.

“Now, four months after beginning to walk again, I’ve become aware that the tension toward things has already dwindled–the plate of pasta made with a bit more care has become again a normal plate of pasta. Things are once again under the umbrella of my measure and my gratification…What is the road that can restore me to that condition, that can make me always live that experience?”

We can all see ourselves in this situation: if we do not continually see being vibrate in us, everything goes flat again and it becomes increasingly urgent for us to know what road can restore us to that condition that makes it possible not to take everything for granted, but to be surprised by everything.

In order to answer this question, you have to understand why this happens to us. Why, after an experience like the one described, do we return to taking everything for granted and not being amazed by anything? Fr. Giussani identified the reasons in What We Hold Dearest, the book of the Equipe (responsibles meeting) of university students published this year:

1) This happens–says Giussani–because of a weak reason that, being unable to grasp the presence of things present, leads us to take everything for granted. Fragile reason is the cause for the fact that reality does not have a grasp on us, does not strike us, and everything becomes gray again. This use of reason leads to an inevitable consequence.

2) A division between acknowledgment and affection, between acknowledgment and being attached to the acknowledgment: the “I” remains divided between the acknowledgment (which remains abstract) and the affection (which vacillates). Since reason is not able to reach reality, affection does not adhere, remains vacillating, and nothing “takes.”

Fr. Giussani also offers us an example of this: “In the beginning of the modern age, Petrarch acknowledged all the Christian doctrine; he felt it even better than we do, but his sensitivity or affection vacillated, autonomous” (Ciò che abbiamo di più caro. 1988-1989 [What We Hold Dearest], Bur, Milan, 2011, p. 156). That is, just affirming Christian doctrine as discourse is not able to engage affection, generating that unity of reason and affection without which one does not know, and the “I” remains divided. We can affirm Christian doctrine (just as we can declare that the sky exists) as an abstract a priori: but there is no vibration, no attachment, nothing outside us that saves us from ourselves and our measure. This is “the anorexia of the human” at the origin of the confusion, the bewilderment, the uncertainty we so often find ourselves experiencing in these times, in which we find ourselves vacillating, like a stone bowled over by opinions, by moods, being unable to attach itself to something real that is present, nor to become truly interested in anything. This anorexia is not resolved by increasing discourses, but by educating reason to open itself to the “language of being.”

The meaning of this openness to being is well documented by an episode of Fr. Giussani’s life that has always struck me. Writing to Angelo Majo, he describes what he sees in those who are his friends; “A few evenings ago, thinking, I discovered that my one true friend is you.” Why did he consider him a friend? Because “I can’t manage to catch that ineffable and total vibration in my being before ‘things’ and ‘people’ except in your way of reacting” (Lettere di fede e di amicizia ad Angelo Majo [Letters of Faith and Friendship to Angelo Majo], San Paolo, Cinisello Balsamo, 2007, p. 103). Among the many things that Giussani could look at to identify those who were friends to him, what does he indicate? Once again he blows us away: it is not any particular intelligence, not a capacity to dominate his thought, not an admirable ethical coherence, but the “ineffable and total vibration” before being that he grasps in the way his friend reacts. So then you understand why the root of the question is the fact that we struggle, are not used to seeing as presence a present leaf, are not used to grasping, to fixing as presence, the things present. It is not that you deny the presence of things. You simply take them for granted. This is seen in the fact that there is not even one instant of wonder. It is not that we have done anything mistaken, simply that we have not discovered being vibrating within us. We all know how unbearable life can become when it is so void of wonder.

One understands, then, the urgency of becoming used to fixing as presence the things present, in such a way that we can see our “I” vibrate, whatever the circumstance may be. And since things are present in any case, it is not the things that are missing, but an “I” capable of becoming aware of what exists. This makes us understand the point to which the rationalistic climate we live in affects us, much more than we realize. We see it in how hard it is for us to acknowledge reality according to its full nature. Today a positivist conception dominates, according to its new translations. But as the Pope reminded us in Germany, “the positivist world view... in and of itself is not a sufficient culture corresponding to the full breadth of the human condition. Where positivist reason considers itself the only sufficient culture and banishes all other cultural realities to the status of subcultures, it diminishes man; indeed, it threatens his humanity.” (Benedict XVI, Address During the Visit to the Bundestag, Berlin, September 22, 2011). For this reason, in the second chapter of The Religious Sense, Fr. Giussani clearly identifies our task: “The truly interesting question for man is neither logic, a fascinating game, nor demonstration, an inviting curiosity. Rather, the intriguing problem for man is how to adhere to reality, to become aware of reality. This is a matter of being compelled by reality, not one of logical consistency. To acknowledge a mother’s love for her child is not the conclusion of a logical process: it is evident, a certainty, or a proposal made by reality whose existence one must admit” (L. Giussani, The Religious Sense, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 1997, p. 14). Only the evidence of reality can be so compelling that it forces us to acknowledge the things present as presence.

No text can help us to verify whether faith facilitates our acknowledgment of reality more than the tenth chapter of The Religious Sense, with which we resume our journey of School of Community, because that chapter is the description of what happens in a man before the impressiveness of reality. Aware that we are immersed in an era of ideologies (rationalism, positivism) that leads us to use reason in a reduced way, and thus to look at reality according to this reduction, right from the beginning Fr. Giussani establishes a principle of method for a battle against ideology: starting from experience, because reality–he always taught us–makes itself transparent in experience. This methodological principle, which he establishes in the first chapter of The Religious Sense, is decisive for facing the most crucial chapter of the whole book, which is defined by Fr. Giussani with these words, “The tenth chapter of The Religious Sense is the key to our way of thinking” (“A New Man,” Traces, no. 3 [March], 1999, p. VII).

Right from the first lines of the chapter, he invites us to look at the structure of our original reaction before reality, in such a way that from the first repercussion, the ideological reduction does not win in us. Next, he describes what it means to follow that provocation of reality to its origin, without blocking it halfway along the road. In this chapter, Fr. Giussani describes the true journey of reason and affection in the face of reality, a journey that must be travelled by those who want to stop taking everything for granted.

Therefore, he begins with a question: If these ultimate questions that constitute the religious sense are the stuff of human consciousness, of human reason, how do they arise? “To answer such a question, we must identify how a person reacts to reality” (The Religious Sense, op. cit., p. 100). Fr. Giussani offers us a method: “If an individual becomes aware of his constitutive factors by observing himself in action, we need to observe this human dynamic in its impact with reality, an impact which sets in motion the mechanism revealing these factors” (Ibid.).

And he adds a fundamental note: “If an individual were to barely live the impact with reality [how often we desire to spare ourselves this, and above all our children!], because, for example, he had not had to struggle, he would scarcely possess a sense of his own consciousness [it is the “I” that is diminished; the “I” that is missing], would be less aware of his reason’s energy and vibration.” In fact, it is in our relationship with reality that we see growth in the sense of our consciousness, the energy and vibration of reason. If, therefore, we want to spare ourselves the impact with reality, substituting it with discourses or comments, the inevitable consequence will be that we will no longer vibrate in front of reality.

With every sentence of this chapter, we should look at our experience, our reaction before things, in order not to deal with the entire tenth chapter by substituting the repercussion of being with our comments on the text, speaking about wonder instead of being wonderstruck (not to mention the fact that this is extremely boring, as well as useless!). The first point Fr. Giussani deals with in the chapter is precisely this: awe of the presence.

2. Awe of the “presence”

To help us acknowledge things present as presence, what is the first brilliant move Fr. Giussani makes? Breaking the obviousness with which we look at reality, our way of taking everything for granted. As we have seen, we usually look at reality as obvious. To rip away this obviousness, Giussani asks us to make an effort of imagination: “Picture yourself being born, coming out of your mother’s womb at the age you are now at this very moment in terms of your development and consciousness. What would be the first, absolutely your initial reaction?” (Ibid.). We have to try to identify with the experience Fr. Giussani suggests to us, trying to follow it. The simplest form is finding again in your own experience a fact that documents it, for example, the one my friend Alexandre, a doctor in Brazil, related to me.

This summer, he and a group of Portuguese-speaking university friends (from Brazil, Portugal, and Mozambique) went for a hike to Colle San Carlo, in La Thuile. As he was walking, he thought about what he would say when they arrived. He thought to himself, “I’ll tell them to look at the panorama, we’ll sing a few songs, etc.” But as soon as they arrived, with Mont Blanc in front of them, which many were seeing for the first time, they were all silent. While they were there, all quiet, they heard a second group arriving, those who had remained further behind. Our doctor began to think what he would say at their arrival: “I’ll make them be quiet.” But as he was thinking this, they arrived and the majesty of the presence of Mont Blanc was so compelling that they, too, remained in silence. This small fact shows how the image used by Fr. Giussani of opening our eyes with the awareness we have now is not straining the concept at all.

“If I were to open my eyes for the first time in this instant, emerging from my mother’s womb, I would be overpowered by the wonder and awe of things as a ‘presence.’ I would be bowled over and amazed by the stupefying repercussion of a presence which is expressed in current language by the word ‘thing’” (The Religious Sense, op. cit., p. 100). This is the same invitation that the Pope proposes to us: “How can reason rediscover its true greatness, without being sidetracked into irrationality? How can nature reassert itself in its true depth, with all its demands, with all its directives?... The windows must be flung open again, we must see the wide world, the sky and the earth once more and learn to make proper use of all this” (Benedict XVI, Address During the Visit to the Bundestag, Berlin, September 22, 2011).

For our friends on the hike, just as for us, these things are not obvious, and you can see it by the wonder they generate. Just read the adjectives with which Giussani describes this repercussion: “overpowered,” bowled over by the repercussion, and “amazed,” filled with this awe, with this wonder, that no situation in this world, no crisis, can prevent–nothing can stop the repercussion of being, stop us from being filled with this fullness, or stop it from making our whole being vibrate and begin anew.

“Being: not as some abstract entity, but as presence, a presence which I do not myself make, which I find. A presence which imposes itself upon me” (The Religious Sense, op. cit., p. 101). So then I manage to fix as presence the present things. And this leads, in the life of each person, to the reawakening of our own human “I.” We know well the degree of intensity our “I” acquires when this happens, what a vibration one experiences.

“The awe, the marvel of this reality which imposes itself upon me, of this presence which reaches me, is at the origin of the awakening of human consciousness” (Ibid.). I discover in myself an unknown intensity, because of “this original experience of the ‘other.’ A baby lives this experience without being aware of it, because he is not yet completely conscious. But the adult who does not live it or does not consciously perceive it, is less than a baby. That person is atrophied” (Ibid.). This is the lack of the “I,” which is atrophied, like a stone that is not amazed by the beauty of the mountains, that does not vibrate before the being of things. We understand what would become of our life if we lost this capacity for wonder! We understand what a gift the Christian event is, how it makes us more capable of wonder about everything. Heschel is right: “Devoid of wonder, we remain deaf to the sublime” (Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, New York, 1955, p. 251). In other words, we lose the best. No artificially created distraction, like those today’s society invents, can restore it to us.

“Therefore, the very first sense of the human being is that of facing a reality which is not his, which exists independently of him, and upon which he depends.” It exists! It exists! It exists! “Empirically translated, it is the original perception of a given” (The Religious Sense, op.cit., p. 101). According to its meaning as a past participle, “given” implies that there is something that “gives.” Everything is given to me, a gift. Can we imagine what life would be like if we experienced every thing as “given,” as gift, if we acknowledged any present thing in this way and if it made us vibrate? Any kind of circumstance would be different.

A friend writes me:

“Hi, Julián! I’m writing from the hospital room of my mother, who has undergone minor surgery. What a miracle this day has been, because it started out with nothing taken for granted; I felt like I was living what is described in the tenth chapter of The Religious Sense. Seeing my mother go down to the operating room under anesthesia made me look at her with great tenderness, not only because she is my mother, but because this morning her presence re-awoke me to the awareness that the greatest and deepest evidence I perceive is that I do not make myself. I am not making myself. I do not give myself being. I do not give myself the reality that I am. I am ‘given’! It was not taken for granted this morning that my mother is given to me, and that I looked at myself as a gift!”

What is the decisive obstacle to this way of looking? That, as we have seen, we take for granted this given, do not perceive reality as given. We start out by passing over the being there, the giving of itself, the existing of things. What is the most evident sign that we pass over the “being there” of things? The lack of wonder. Unfortunately, this is our most common, our most deeply rooted position before reality. “We are not used to looking at the things present as presence”–this is the importance of what Fr. Giussani tells us. This is why it is so rare to see being vibrate in someone! And when we see it vibrate in us, it is a wonder, because it so rarely happens.

At this point, we can understand better how decisive it is for each of us to learn the attitude suggested by Fr. Giussani until it becomes habitual: “the very word ‘given’ is also vibrant with an activity, in front of which I am passive: and it is a passivity which makes up my original activity of receiving, taking note, recognizing” (The Religious Sense, p. 101). The first activity, friends, is this passivity, without which I do not become aware of the given, of reality as given, as a gift that is given to me. If we do not want to lose reality in every detail, this indication of Fr. Giussani’s must become familiar in us: the first activity is passivity. But we have to be careful of the type of passivity we are talking about, in order not to come to the usual conclusion that nothing need be done. The passivity he speaks of is “receiving, taking note, recognizing” reality as given. That is, precisely the opposite of taking it for granted. How can we tell that we are living the same experience Fr. Giussani speaks of, and not just repeating a slogan? By the wonder, the reawakening of the human in us.

Presence is so compelling that it facilitates our becoming aware of it, because “ ‘evidence is an inexorable presence!’ Becoming aware of an inexorable presence!” (Ibid., p. 101). What a succinct expression: becoming aware of an inexorable presence. This is treating the things present as presence: becoming aware of an inexorable presence. This becoming aware can never be reduced to “a cold observation”–it is a “wonder pregnant with an attraction.” It is the “awe which awakens the ultimate question within us” (Ibid.), the religious question. In fact, religiosity is born of this attraction. The first sentiment of man is this attraction. Fear–which is often indicated as the origin of religiosity–emerges only in a second moment. “Religiosity is, first of all, the affirmation and development of the attraction. [This is what we need, the development of the attraction of being]. A true seeker’s disposition is laden with a prior evidence and an awe: the wonder of the presence attracts me, and that is how the search within me breaks out” (Ibid., p. 102).

What simplicity is needed to let myself be attracted by that presence, which, because of the vibration it provokes in me, becomes so interesting as to trigger the search! If this search does not stop, does not get blocked, then to explain that presence, that given, we have to admit something other. But often we get blocked in this search, and this is seen by the innumerable times we hear the question, “Why, in the face of reality, do we always have to draw in the Mystery, the You, God?” This is asked as if the reference to another factor beyond and within what one sees were not contained in what one sees, in the experience of what one sees, in the given, but were our own construction. Certainly, this reference is accepted by the subject, but it belongs to the object, to the thing, to the experience of the thing.

For this reason, one who starts from what exists, as a true seeker, does not block the reference inscribed in the experience of things, and does not block his curiosity, his desire to understand deep down, to explain the given exhaustively; he cannot help but acknowledge something other as part of the presence that exists. This is described in the dialogue between God and Job: “Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundations?” or, in other words, were you the one who generated this reality that amazes you? “Tell me, since you are so well informed! Who decided the dimension of it, do you know? Or who stretched the measuring line across it?” (Job 38:4-5).

All that exists cries out its dependence on an Other. Therefore, there is nothing more suitable, more in keeping with human nature, than being possessed, because of an original dependence. In fact, our nature is that of being created, and our reason is fulfilled in acknowledging the ultimate implication within the being of things. If one denies the reference, if he rejects the beyond, if he denies the thing, the experience of the thing, he destroys it. In front of the colossal gratuitousness of reality, there is a kind of strange paralysis of reason, which becomes blocked. But if one denies this, he denies the thing. It is as if within things there were an invitation, not added by the subject, but acknowledged by the subject, because it is contained in the very phenomenon of the presence. For this reason, the first original intuition is wonder at the given. Please do not take it for granted, reducing experience again to thought. Thought about wonder is not wonder, just as thought about being in love is not being in love. For this reason, Fr. Giussani, in the fourth section of the tenth chapter, on the dependent “I,” makes us understand whether we have truly experienced what he says or whether we have simply followed the logic of a discourse without even an instant of wonder.

3. The dependent “I”

“When an individual is reawakened within his being by the presence, the attraction, the awe, he is grateful, joyful, because this presence can be beneficial and providential. The human being becomes aware of himself as ‘I,’ recovers this original awe with a depth that establishes the measure, the stature of his identity” (The Religious Sense, op. cit., p. 105).

The test that I experience the repercussion of being is, first, that my “I” is reawakened. We observe it often: we recognize that something has happened to someone because the “I” of that person has been reawakened (we ask right away, “Hey, what’s happened to you?”). Second, I am grateful and glad (like the friend who had the accident). I understand that the repercussion happened in me because I perceive in myself gratefulness, gladness for this presence (I can be in the hospital, like the friend in the letter, but I am grateful and glad because this presence exists). Third, this makes me aware of myself, to the point that, fourth, the depth of the wonder establishes the importance of my identity. Look at what the criterion of measure of my identity is! University degrees, the money we earn, or our job title do not establish the importance of our identity: it lies in the depth of wonder that makes me aware of myself.

“At this moment, if I am attentive, that is, if I am mature, then I cannot deny that the greatest and most profound evidence is that I do not make myself, I am not making myself. I do not give myself being, or the reality which I am. I am ‘given.’ This is the moment of maturity when I discover myself to be dependent upon something else” (Ibid.).

Each of us must ask ourselves whether the “I do not make myself” is “the greatest evidence.” For us, the bottle or the glass is evident, but the fact that “I do not make myself” is not so evident, and this is seen in the question that often returns among us: Why, before reality and my “I,” do I have to say You? Isn’t some passage missing?

To answer, we have to try to follow Giussani on his journey to the depth of reality, if we want to grasp its origin. “If I descend to my very depths, where do I spring from? Not from myself: from something else. This is the perception of myself as a gushing stream born from a spring, from something else, more than me, and by which I am made.” And he gives a very beautiful example: “If a stream rushing forth from a spring could think, it would perceive, at the bottom of its fresh surging, an origin it does not know, which is other than itself” (Ibid.).

“Descend to my very depths” is an invitation to a true, not fragile, use of reason, the only one able to overcome the separation between acknowledgment and affection. Our difficulty in doing it, in following Fr. Giussani in this, is a sign of our lack of familiarity with a complete, not positivist, use of reason. Our difficulty in arriving deep down makes us think it is a matter of a mental operation, a complication, a sort of creation, and that, in the final analysis, the You is the fruit of our effort. What a sclerosis of the “I” and of reason! What a lack of the “I”! And what a lack of familiarity with an adequate use of reason! We can see it when we learn mathematics: in order not to make a mistake we have to go through all the passages, step by step. Everything seems so artificial! And why? Because of a lack of familiarity with an adequate use of reason. In fact, when we have learned mathematics, everything becomes agile, swift, and fascinating. Or again, when one begins to play piano, one’s hands seem as if they were in a cast. But how delightful once the agility of our fingers enables us to enjoy Mozart!

We do not have the patience to do this work that Fr. Giussani constantly invites us to do. It seems complicated and artificial. We mistake sentiment for reason, because it seems easier, more immediate: if I feel it, it exists, and if I don’t feel it, it doesn’t exist. This is our “logical” intelligence! At this point, each of us has to decide whether we will follow Fr. Giussani, descending to our very depths, in learning this use of reason to acknowledge things present as presence, or whether we prefer to do something else, choosing not to follow him. Since we are not used to making this journey, we prefer to do something else (read, repeat sentences) instead of working to learn to use reason like him. How often we succumb to the temptation to escape! This is why we remain confused, uncertain, bowled over like a stone by opinions.

Only those who follow Giussani on the journey that he indicates to us will be able to see happening in themselves that vibration that invades us when we truly enter into relationship with Being; just as each of us sees our “I” vibrate before the “you” of the beloved. A man can say “You” with all the vibration that the being of his beloved provokes in him. How he would rebel if someone who lacked this familiarity said that vibration was just a mental operation, a complication! It is like seeing the beloved reduced by the cold gaze of another. But if we do not follow Giussani this far, everything will become flat again, notwithstanding all our comments, because we will not acquire that familiarity with a use of reason able to make us truly adhere to reality and to stop us from continuing to vacillate according to our moods. Everything has the nature of sign, stream. The stream implicates the source. Knowing means making the journey that goes from the stream to the source. This is the true, not fragile, use of reason.

If one were to say “I” with all the awareness of what is happening now, seeing himself given being–of which the increase of being that the “you” of the person provokes in him is only a pale reflection–with what wonderful vibration should he be able to say, “I am you-who-make-me”! (Ibid.). As Fr. Giussani testifies to us, I cannot think of that source that is “more than myself” without trembling and attraction. But for us, saying “You” is almost the same as zero. Do you understand what we are missing? We know–it is not that we do not know–but knowing it does not make it happen. Only an education makes life different. This vibration is not some kind of sentimentalism; it is “a judgment that sweeps along all my sensitivity” ( “A New Man,” op. cit., p. IX), the deeply moved awareness of an adult before the You who gives me being. For this reason, the Pope says that “the Church opens herself to the world, not in order to win men for an institution with its own claims to power, but in order to lead them to themselves by leading them to Him of whom each person can say with Saint Augustine: He is closer to me than I am to myself (cf., Confessions, III,6,11)” (Benedict XVI, Meeting with Catholics Engaged in the Life of the Church and Society, Frieburg im Breisgau, September 25, 2011).

In fact, for my reason to be affective, it needs to be true reason, that descends to the point of reaching the real You from which it flows–not a fragile reason. If reason does not reach reality, affection remains detached and vacillating. The division between reason and reality generates a division between acknowledgment and affection. Reason is not analytical lucidity; it is a bond with reality. Therefore, Fr. Giussani says that true reason is discovered in John and Andrew, because they were “seized.” In fact, unless reason reaches reality and bonds us to it, we continue to vacillate and there is no certainty. This was documented clearly in this year’s Rimini Meeting. As Professor Eugenio Mazzarella acutely observed, commenting on the talk by Costantino Esposito in Rimini, “We come into the world, are placed in our being, by Someone... who is and remains our original ‘supply’ of certainty.... Keeping alive this certainty, reviving it in the life of every day and every moment is to recover–regain oneself–in this original bond with Someone who constitutes us, true source of certainty” (“Caro Ferraris, perché qualcuno ci ha voluto nel mondo?” [“Dear Ferraris, why did someone want us in the world?”], ilsussidiario.net, September 19, 2011). This means recovering from the bewilderment into which we so often slide.

So then, you understand the difference between repeating “I-am-you-who-make-me” like a slogan, no matter how true, and saying “I” with the consciousness of an Other who makes me now! If you cannot say “You” with the same emotion, with the same vibration of the first time you discovered yourself in love in front of the beloved, you have not the faintest idea what Fr. Giussani means. Mental complication? Lucubration? Anything but! The difference is seen by what happens in us. In the first case, repeating “I-am-you-who-make-me” like a slogan, nothing happens. Instead, if I say “You” with the consciousness of the Other who is making me now, I cannot avoid a boundless move of emotion. I cannot avoid seeing the emergence of an affection for that You, and at the same time discovering an infinite gratitude because He exists. What a long journey we still have before us, in order to live reality with this intensity, as Fr. Giussani still testifies to us!

“When I examine myself and notice that I am not making myself by myself, then I–with the full and conscious vibration of affection which this word ‘I’ exudes–turn to the Thing that makes me, to the source that causes me to be in this instant, and I can only address it using the word ‘you.’ You-who-make-me is, therefore, what religious tradition calls God–it is that which is more than I, more ‘I’ than I myself. It is that by means of which I am.” (The Religious Sense, op. cit., pp. 105-106). This is hardly just a word! God is my father because He is conceiving me “now.” Outside of this “now,” there is nothing. “No one is as much a father” (Ibid.). For this reason, we always sing with emotion, “When I realize that you are there, / like an echo I hear my voice again / and I am reborn like time from memory” (A. Mascagni, “Il mio volto” [“My Face”], Canti, Cooperativa Editoriale Nuovo Mondo, p. 203).

“To be conscious of oneself right to the core is to perceive, at the depths of the self, an Other. This is prayer: to be conscious of oneself to the very center, to the point of meeting an Other. Thus, prayer is the only human gesture which totally realizes the human being’s stature” (The Religious Sense, op.cit., p. 105). What a difference from the sanctimoniousness and formalism to which we usually reduce prayer! You understand, then, why we tire and escape from it. Instead, those who do not flee, those who become aware of themselves deep down–that is, use reason in a way that is not fragile, but true and complete–begin to be aware that they can stand because they are leaning on an Other, because they are made by an Other. And their life begins to have solid grounding, not sentimental, vacillating, dependent on moods, but certain, because of reason’s bond with reality all the way to its origin.

Let’s help each other immerse ourselves in this and not reduce these things to something taken for granted the minute after we hear them! “Like my voice, which is the echo of a vibration, if I cease the vibration, it no longer exists. Like spring water rising up–it is, in its entirety, derived from its source. And like a flower which depends completely upon the support of its roots” (Ibid.). Voice, spring water, flower: they are images that Fr. Giussani offers to help us realize this now, to overcome the obviousness, the taken-for-grantedness. For this reason, saying “I am” according to the totality of my stature as a human being can only mean saying, “I am made.” “The ultimate equilibrium of life depends upon this”(Ibid.).

How can one see that he has this equilibrium? By the fact that “he exists because he is continually possessed. And, when he recognizes this, then he breathes fully, feels at peace, glad” (Ibid.). Therefore, “true self-consciousness is well portrayed by the baby in the arms of his mother and father” (Ibid.). We can see that this becomes our experience by the fact that, like the baby, we can enter–how important this is today, in the context of a crisis on every level–into any situation of existence, into any circumstance, into any darkness, profoundly tranquil, with a promise of peace and joy. “No curative system can claim this” (Ibid.). Instead, precisely because this true consciousness of ourselves does not become ours, we have to turn to other curative systems, which, however, are incapable of reaching this level of the question, and therefore do not solve things, except by mutilating the person: often, in order to remove the discomfort of certain wounds, we censure our humanity. Great solution! Nobody can fail to see the importance of what we are saying before the challenge of the circumstances we are called to live. Only such a deeply rooted certainty will enable us to build.

Conclusion

What is the formula for the journey to the ultimate meaning of reality? Living the real, Fr. Giussani tells us straightforwardly. You understand, then, the importance of reality for living.

The only condition for being always and truly religious, that is, men (not pious, men!) is always living reality intensely. For this reason, the person who lives reality intensely, even if he is a peasant or she is a housewife, can know reality better than a professor, because the formula of the journey to the meaning of reality is to live reality without preclusion, without negating or forgetting anything.

But, be careful, what does it mean to live reality? Fr. Giussani has a last pearl for us: “Indeed, it would not be human, that is to say, reasonable, to take our experience at face value, to limit it to just the crest of the wave, without going down to the core of its motion.” This is the “positivism that dominates modern man,” that “excludes the call emanating from our original relationship with things, to search for meaning.... Positivism excludes the invitation to discover the meaning addressed to us precisely by our original and immediate impact with reality” (Ibid, pp. 108-109). As the Pope said in Germany, with a luminous image, “In its self-proclaimed exclusivity, the positivist reason which recognizes nothing beyond mere functionality resembles a concrete bunker with no windows, in which we ourselves provide lighting and atmospheric conditions, being no longer willing to obtain either from God’s wide world” (Benedict XVI, Address During the Visit to the Bundestag, Berlin, September 22, 2011).

How can we tell that we are positivist? By the fact that we suffocate inside our concrete bunker. Fr. Giussani offers us all the data so that each person can verify the experience she or he is living. We can give all the interpretations we want, but if we are suffocating in the circumstances, it means that we are positivists (this is the point!). In order to breathe, “the windows must be flung open again, we must see the wide world, the sky and the earth once more,” the Pope tells us, and Fr. Giussani adds, without blocking the world’s “invitation to discover the meaning addressed to us precisely by our original and immediate impact with reality” (The Religious Sense, op. cit. p. 109). For this reason, “the more one lives this level of consciousness in his relationship with things, the more intense the impact with reality, and the more one begins to know mystery” (Ibid.).

This asks of each of us a commitment that nobody can spare us. Therefore, Fr. Giussani concludes the chapter by making us aware that “a trivial relationship with reality, whose most symptomatic aspect is preconception, blocks the authentic religious dimension....”–in other words, ideology, this reduction we so often live because of our cultural situation. “The world is like a word, a ‘logos’ which sends you further, calls you on to another, beyond itself, further up” (Ibid.). For this reason, analogy is the word that “sums up the dynamic structure of the human being’s ‘impact’ with reality” (Ibid.).

What a fascinating adventure, friends! Travelling it all the way, we will be able to testify to everyone a reason capable of acknowledging reality in all its profundity, the only point that enables us to build in a moment in which everything seems to conspire against the renewal of social life. This is our contribution.

HOMILY AT THE MASS

Julián Carrón

Today’s readings tell us that learning to make the journey we have spoken of is not only decisive for the relationship with reality in general, but also for the most real reality of the Christian event: Christ. We can be before the preference of the Mystery and not even realize it.

Today’s entire Liturgy is full of this predilection, this preference. “The vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel, and the men of Judah are His cherished plant” (Is 5:7). What shows this preference? The fact that God “spaded it, cleared it of stones, and planted the choicest vines; within it he built a watchtower, and hewed out a wine press” (Is 5:2). He surrounded it with that unique preference, but not just in the beginning: in fact, the Lord sent–as the Gospel says–the prophets, even the Son, to care for it, but the renters did not accept Him, were not aware of that preference, of that gift (cf., Mt 21:22-43). And when we do not become aware of the gift of reality that we receive from the Mystery, we see disasters multiply. In fact, after this rejection, what happens? “It shall not be pruned or hoed, but overgrown with thorns and briers” (Is 5:5-6). Life is reduced to this: a desert, everything becomes flat, everything becomes gray.

By presenting them in the Liturgy, the Church makes these parables from Isaiah and the Gospel topical for us, to call us to the fact that we, now, are the vineyard of the Lord. The Lord has generated the Church, cared for her, bought her with the price of His Son’s blood. We can say, “We are the cherished vineyard.” God does not abandon His people, and continues to send us messengers, “witnesses”–as our Archbishop reminded us last Sunday–who care for the vineyard, so that it will not become a desert. But many times we not only reject the prophets, like the people of the Old Covenant, but we also reject the Son. As Archbishop Scola told us, quoting Giovanni Battista Montini, “Christ is unknown, forgotten, absent in most of contemporary culture.” This causes people “to be unable to see how He is to their advantage in their daily life and for their loved ones” (A. Scola, Homily at his entrance into the Diocese, Milan, September 25, 2011).

The Pope–another messenger–reminded us of this in Germany: “We have been seeing substantial numbers of the baptized drifting away from Church life” (Benedict XVI, Meeting with Catholics Engaged in the Life of the Church and Society, Freiburg im Breisgau, September 25, 2011). And again, “The real crisis facing the Church in the Western world is a crisis of faith” (Benedict XVI, Meeting with the Council of the Central Committee of German Catholics, Freiburg im Breisgau, September 24, 2011). We see how the parable continues to come true, exactly the same: we, too, can also reject all the messengers, even the Son. We are seeing the consequence in ourselves and in social life: this “massive abandonment of Christian practice” must implicate–said Cardinal Scola–a “grave detriment for the personal and community life of the Church and for civil society” (A. Scola, op.cit.). But the Lord continues to send us messengers, witnesses, even now, from the Pope to our Archbishop, together with many changed people in our midst. Through them Christ continues to call us, to attract us toward Himself so our vineyard will not become a desert, but will bear fruit. Because, as the Pope said, “in the last analysis, the renewal of the Church will only come about through openness to conversion and through renewed faith” (Benedict XVI, Homily at Mass, Freiburg im Breisgau, September 25, 2011). Conversion is nothing other than building on the stone that others cast aside and that we, too, cast aside at times; it is building on the Lord because, as the Pope affirmed, “He is always close to us... and His heart aches for us, He reaches out to us.... He is waiting for us to say ‘yes,’ He, as it were, begs us to say ‘yes.’” (Benedict XVI, op.cit. ).

Today, before this begging of Christ for our “yes,” our life is at a decisive point. “In order to communicate Himself to men, Christ chose to need men” (A. Scola, op.cit.), the Archbishop reminded us. God needs us. We have been called to collaborate in His mission, to witness that the only stone upon which one can truly build is He alone.