Traces, No. 2, April 2022

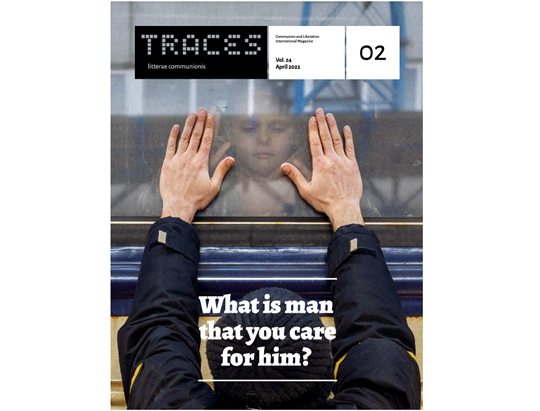

UnassailableThe conflict in Ukraine has awakened a distress that has all the weight of history and of the future, with its rupture of the global order and of the tragic illusion that it can be recreated at the expense of the absolute concreteness of the person. What is happening reminds all of us to think about our destiny. Together with the pain and fear, we see the explosion of that which defines humanity more than DNA ever could: the irrepressible need for justice, for truth, and for meaning in this life. These are unquenchable desires that power cannot crush. This truth is in the faces of all the wounded and the refugees, and it was in the faces of Tetjana and her children, who were killed as they tried to flee, beside them their suitcases that could not fit a full life inside them. It is in the gloomy lines of tanks in the snow, the raids gutting entire buildings, the sound of sirens echoing even in the ears of those now far away, and in the frost and the hunger in the bunkers. Then there is the hatred that devours relationships, the adolescent faces of the soldiers, the young father who ran in vain to the hospital with little Kirill in his arms, the doctors operating by the light of cell phones, the darkness, the silence, and all those good-byes said without words on railway platforms.

“What is man that you are mindful of him, mere mortals that you care for them?” Man, who seems to be of negligible significance, who can be torn out of the world. And yet, he belongs to a different order, as Giussani says in To Give One’s Life for the Work of Another, so much so that all of reality receives its meaning from “a point beyond our grasp, yet in which everything is mirrored: the I.” This beacon is a

light by which we judge both our personal and shared history. It is the factor that cannot be manipulated. And it is a beacon because, if it is fully self-aware, it is free even in the face of oppression. This is what we seek in the witnesses set forth this issue, in the people who are facing the present head on, including in their attempts at dialogue and in welcoming strangers, allowing us to reach the same conclusion that the writer Vasilij Grossman was able to reach: no violence can eliminate the unassailable heart of each person because this heart is our relationship with God. Giving this mystery room to breathe introduces a change even in the darkest moments of humanity.

Recognizing the absolute impossibility of doing justice and the total need for something else that frees us reveals the “anthropocentric presumption,” as Giussani calls it, “according to which man is capable of saving himself,” according to which we claim we can change the world even after excising the one thing capable of changing life: the presence of God, who makes Himself visible through men and women who truly love with a different logic, which comes purely as the result of having an encounter with Christ. Christ, a man who, living in the immensity of the Roman Empire, silently conquered death and did not distance himself in his relationship with the Father, not even on the cross. “Christ’s resurrection is not an event of the past,” as the pope’s words in the CL Easter Poster put it; instead, “it contains a vital power which has penetrated the world.”