Traces, no. 2, April 2024

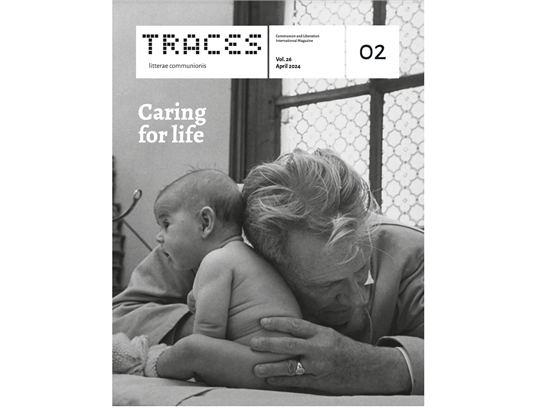

The end of lifeAs you will find well expressed by philosopher Francesco Botturi in the first article of this issue, the place given to those who suffer, and thus to those who care for life even in the most difficult situations, is the measure of a civilization’s stature. The current technocratic paradigm has transformed every situation “into a ‘problem’ to solve rather than facing it as an enigma to which you respond.” Pain, illness, and death challenge this superficiality and put to the test “the desire dwelling in the human heart” that life have meaning and that it not end.

The scientific, ethical, legal, and political issues that fragment the “end-of-life” debate, one of the most dramatic of our time, must take into consideration the individual, unique experience of the sick, their families, and those who care for them. Abstractions are not allowed, especially in the case of a patient’s request to put an end to her or his condition. “Behind the desire for death, there is a feeling of uselessness and a sense that it is impossible to find any meaning for pain,” as Davide Prosperi said recently in the context of a series of gatherings with physicians, nurses, bioethicists, and legal experts who deal with these themes daily and compare ideas and experiences in order to judge all the factors in play. Prosperi continued: “Medical, social services, and legal choices touch a need that life be useful, a need that cannot find an answer in these decisions. Christ did not eliminate the desert, but instead He became our companion on the journey through it. This judgment is grounded in a tradition, a vision of life, and we have the responsibility to offer it to people today, explaining our reasons, starting from experience.”

The Close-up section of this issue describes the fruit of that work together, a presence that becomes companionship, through the stories of people in situations of suffering and sometimes incurable illness. A mostly hidden revolution emerges, one happening daily in homes and hospital rooms, silent but capable of dismantling any ideology that would eliminate suffering by removing humanity. “And it is what we secretly desire,” said Cardinal Ratzinger in 1978. “Yes, we find it too difficult to be human beings.” But “God did not take away our humanity: He shares it with us.” Care for life, for the great mystery of the person, in the dignity of every moment, is the only thing that allows space for questions, at times atrocious, or the silence In front of that which is unspeakable and sacred. What is freedom? What is the value of an existence? Who decides? What does it mean to honor life? To what point should we push? With death, does everything end in nothingness? Entering into the very delicate questions that emerge in the field of the “right to die” first of all means answering the question about the meaning of life. “Nothing is more difficult for man than to accept and acknowledge the positive nature of life,” wrote Fr. Giussani. “For this reason, euthanasia is a contemporary symbol of man’s absolute despair that governs all of human culture […]. A symbol of the despair in his response to living.” This issue offers the story of a patient who, after great resistance, accepted treatment from just one physician because in him she saw someone for whom “the problem was not not to die but to live.” This is about living even one’s darkest or final moments by entering into the face of that love that gives

life and breath, in that original companionship that is more radical than any solitude. When Fr. Giussani was gravely ill, he was asked whether he felt alone when he suffered greatly. He responded: “I never feel alone, because Christ is the indivisible companion of my ‘I.’”