Traces N.2, February 2020

All the roots of meIt is difficult to find a theme more urgent, one that concerns everyone at every latitude, touching each person, from the elderly, who are increasingly isolated, to youth, described as being “alone together,” to use the expression of Sherry Turkle, a famous American sociologist. Solitude is a given, and it touches the life of each of us. It does not depend on how many bonds we have, our network of relationships, however rich they may or may not be. It is common to feel alone even in moments when we are surrounded by friends. “True solitude does not come from being physically alone but from the discovery that a fundamental problem of ours cannot find its solution in us or in others,” observed Fr. Giussani. “We can well say that the sense of solitude is borne in the very heart of every serious commitment to our own humanity.” There is an ultimate point in the depths of our “I” where we are inexorably alone, because nothing we have in front of us and in which we place our expectations for fulfillment, can satisfy our heart.

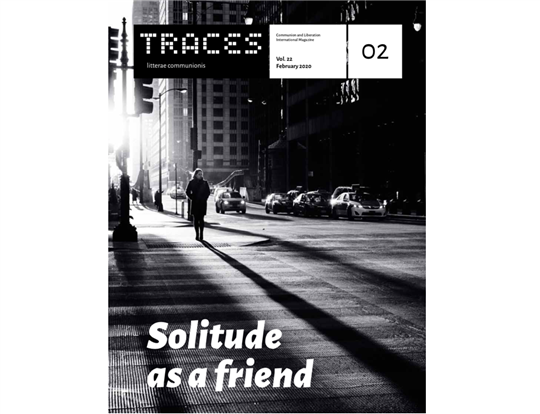

Thus solitude is an inevitable, structural condition. But are we condemned to solitude? Is there no escape from the dramatic experience we all have of a feeling so acute as to be unbearable at times? How much time, energy, and money is spent to elude moments when we are alone with ourselves? Must we resign ourselves to the fact that our own humanity is our enemy? Or is there another possibility?

This is the road we explore in this issue. The opportunity to confront this topic was provided by a conference held in Florence some time ago entitled, “The Enemy Solitude,” which involved a series of talks examining from a medical, psychological, economic, and other points of view this enormous problem facing our society, so widespread that in Great Britain there is even an ad hoc minister to address it. Fr. Julián Carrón’s talk at the gathering, which is published in these pages, opens up a new outlook. Solitude is not necessarily something we must flee. It can be a friend. In fact, it is “the place where we can discover the original companionship” that constitutes us because this is the way human beings are structured: we exist, now, and therefore we are created, wanted, and loved now, regardless of the circumstances in which we live or the problems we have to face. In Generating Traces in the History of the World, Fr. Giussani noted that the Christian encounter, “which is all-encompassing by its very nature, in time becomes the

true shape of every relationship, the true form by which I look at nature, at myself, at others, and at things.” He continues: “When an encounter is all-embracing, it becomes the shape, not only the sphere, of relationships. It not only establishes a companionship as the place where relationships exist but it is the form by which they are conceived of and lived out.” Christ can begin to “give shape” to life, and shape our awareness of ourselves, only when He sets roots in the depths of our “I”; that is, when He responds to this ultimate solitude. In doing so, He causes us to discover, with a jolt of wonder, that no matter what happens, we are never truly alone, because He exists.