“Communion is Liberation”. 1969, the birth of a name

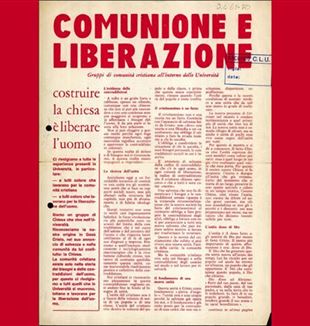

Fifty years ago, at the State University in Milan, a document was circulated that gave the movement, which was growing around Fr. Giussani, its name. This is how Savorana recounts the event in his biography of Fr. Giussani.In November of 1969, a flier bearing a strange header began to circulate at the State University of Milan. “Communion and Liberation”, it read; and the subtitle was similarly unusual: “To build the Church is to free mankind”.

Pier Alberto Bertazzi, who was among the protagonists of that initiative, recalls how it began: “Our endeavour seemed to be working, at least for us, We felt as though the experience of the movement we had begun in high school was going forward”. So the students decided to change from a flier to a printed bulletin. But the name had to be more direct. “I remember that we wanted to talk about two things: liberation- in other words, the need we shared with everyone else- and communion, the thing that, in our experience, was capable of achieving it. Communion and liberation: the two things to hold dear.” Bertazzi asked is this could be the new title, but the majority felt that it was too heavy for a student bulletin. One late afternoon in the fall of 1969, at the offices of Jaca Book on Via Bagutta, he talked it over with Sante Bagnoli, the publishing company’s director and one of Giussani’s closest collaborators. “In the end, he, too, thought it could work. And since he was an editor by profession, the title was accepted”.

Over the course of a few months, they printed three issues of the bulletin, one red and two blue. In the words of Bertazzi, “There were small groups of our friends in all the different departments, and all of them began to use that name, together with the proto-Christian symbol of a stylized fish (ι′χθυ′ς) for their fliers, notices, and the like.” Without anyone having planned it, Communion and Liberation began to become a sign of recognition. “First the others started to call us the ones of, the groups of ‘Communion and Liberation’, referring to our print-outs.”

A few weeks after the first bulletin was circulated at the State University, the unusual formation appeared at Catholic as well. Cardinal Giacomo Biffi described how it happened. In 1969 he was a parish priest in Milan. Concerned about the situation within the Church, he wondered to himself if perhaps “the Holy Spirit had abandoned its Church”. He recalled that “everything was falling apart, and nothing was bouncing back”, During those months, Biffi, wrote a small book, Alla destra del Padre (At the right hand of the Father). He ran into some difficulty finding a publisher until the book was accepted by Vita e Pensiero, the publishing company of the Catholic University. Walking onto the campus in December 1969, Biffi came upon a poster with the heading “Communion and Liberation” and underneath a few principles and an invitation to get together for whoever was interested. It was a surprise for Biffi: “Like a ray of sunlight after an absolutely leaden sky. I didn’t know they were following Giussani; that I learned only later. As I understand, that was actually the very first day that, out of the ashes of the old GS, the new movement called ‘Communion and Liberation’ was born”.

The students found support at the Péguy Centre offices at 16 Via Ariosto. One of the put a paper signed “Communion and Liberation” on the door of the room they used there. And one day, a day Bertazzi remembers clearly, the poster caught Giussani’s eye. “There”. He exclaimed, looking at it: “we are the same name the university students gave themselves. Because communion is liberation”.

The question remains of how it was possible that an answer began to take shape in the midst of the troubles that embroiled everyone during the Sixty-eight affair. To all the students who saw him at Catholic and asked him, “What should we reply? What do we have to do?” Giussani would say, somewhat provocatively, “Well, do you fell like you love human freedom any less that your protesting classmates do? Do you love the freedom of life less? Do you feel less the desire for authentic justice?” And they answered him no, and told him that this was exactly the cause of their predicament.

Under the circumstance, the students and Giussani said to themselves, “We too, want the liberation of man and of society, if possible even more than they do, because we announce Christ to the world, Christ who came to truly free humankind”. For Giussani, the proper response to give the others was this: “the more we edify the Church the more we will contribute to the true liberation of the world, continually correcting the widespread illusion”. And in order not to leave any room for his intentions to be misunderstood, he reiterated the response to the provocation of the protest: “Multiply {…} the Christian community” because “this is our contribution to our fellow man. Open to try even the most infinitesimal idea that the others’ intuition puts before us, ready to cooperate with every fact that, in the light of faith, seems right to us”.

On 9 November 1969, Giussani participated in a student meeting. It was entitled “University and high school study groups”. A five-page mimeograph report survives. Giussani spoke at a certain point, explaining, “A study group, to the extent that it analyses the situation, cannot be isolated from the phenomenon of the Christian community within the environment as a whole”.

He went on to clarify: [A]theory on the situation, […]a true reading of the needs involved can only come about by sharing in them; […] otherwise the reading becomes an a priori one, “dictated by “whatever theories happen to be in vogue”. For Giussani, the only practical and theoretical a priori was Christian communion: “To share need is the only way to understand it, but that understanding would be the wordly reality of it did not start from the Christian tradition. […] the beginning of presence within the environment is not the environment itself, but something that comes before. […] The announcement does not come from how smart we are at resolving the issues, but come before, it is something that is given to use and in which we find ourselves, from which we are constantly beginning”. something that come before: this was the content of the challenge Giussani laid sown. He knew it went against the general grain, which demanded analysis first and emphasized the urgency of doing.

According to Giancarlo Cesana, at the time a medical student at the State University of Milan, and later a university professor, in that turbulent moment Giussani re-proposed Christianity in its original nature and strength, with an “experimental framework” that faced objections and opposition openly.

Cesana came from a leftist background. Then an event in his personal life set everything within him in motion: “I fell in love. She wasn’t having any of it, and I thought, seriously? I’m fighting a revolution to change the world, and the one thing I ask for I don’t have? How is that fair?” It was at tat precise moment that he stumbled upon Giussani. It happened in a strange way. “I had gone to see a friend who was on vacation with his parish youth group. […] After travelling all night, I was in the big tent they were using as dining hall […]. Exhausted and distracted, I sat a table where a tape recorder was lying. Not knowing what to do, I pushed one of the buttons”. Out of the recorder them came the rough voice of a man saying, “What were the first words Jesus used to begin his mission?’ Silence. The guy with the rough voice repeated the question. Another voice replied, ‘He said, “Love one another/”’ […] ‘No, and they wouldn’t have understood if he had. To explain what Jesus said when he began his mission, […] I want to go back to an experience from last night. I had a tip-top wine, a Barolo. How do you tell if a wine is good?’ An immediate answer from the group: ‘You have to drink it!’ ‘That’s it, […] Jesus started out like that. When people asked him, “But who are you?” he didn’t say, “I’m the Son of God, my mother conceived me virginally“”, Cesana paraphrases. “’He didn’t answer like that; they wouldn’t have understood him. Instead he said to them, “Come and see”. And they went and stayed with him all afternoon until evening, and tried it out, and found that it worked for them. There, that’s how Jesus started out”’.

Hearing those words, stumbling upon this “experimental framework for the Christian experience was like a veil being lifted, […] like fog clearing”. He recalls, “I immediately tried to find out who that man was who was speaking, and they told me it was Fr. Giussani”.

For Cesana that encounter was the start of a radical transformation in his life: “With him we were obliged to rethink everything. Our way of making judgements, our way of discussing, our language…It was an extremely rich experience”.

Giussani spoke about this same revolution at a gathering of adults at the Péguy Centre on 26 November 1969: “The point where Christian discourse radically wards against any ideology is the person”. This is because “the definitive resolution of the problem of the world passes through the relationship of God with an individual, that is, passes through the phenomenon of the person. The person is the point where the divine rocket touches down to reduce to shambles, or to out back in order the great earthquake of the world”. Because of this, it is “in the transformation of the person that most just and healthy revolution takes place. It is the Christian concept of conversion”.

There were two elements not to lose sight of” prayer and friendship. Giussani said that prayer is “the time when a person realizes, recognizes, accepts, cries out to the divine lance that penetrates our existence. So, it is only from prayer that you can unleash action that is real, indomitable, inexhaustible. Even if no one understands you; even if things don’t go as well as you though they would. No one can stop you. You make yourself sure before the universe, sure of an Other”.

As fare as friendship was concerned, the new thing that was taking off during those weeks gave Giussani the occasion to pronounce a warning” “Let’s not sabotage this work, altering its authentic value, as we do all the time”, because friendship is “the relationship that calls you back to the presence that came to be inside you, as if all the atomic energy in the universe were unleashed”.

And he concluded, with a touch of sadness, “My friends, after mush companionship we must recognize that these are the two factors we don’t have. We have It all, except for these two factors because the first is personal, and the second is absolutely personal”. And yet only “this personalness, that we can’t shake off or transfer to someone else, can give rise to the true action that changes society, history, and the world”-action that “does not became presumption”, but is “full of the energy of optimism, which all the others call dream or madness or illusion. But it’s been exactly two thousand years that people live, and build, and understand better and better how this thing, which I called an illusion, is really the dominant factory coming undaunted from within history’”.

At the end of a meeting on 17 December 1969, the following announcement was made for the first time: “The Communion and Liberation group invited any students to meet afterwards just outside the door.” This was a clear indication that the student group was following the reality of the Péguy Centre and the movement that was being reconstituted around Giussani. Giussani added immediately after the announcement, “I ask you to please read the Christmas poster put together by the university student groups of Communion and Liberation”. In his eyes, CL was already an identifiable reality.

(from Alberto Savorana, The Life of Luigi Giussani, pp. 421-425)