A Seed Amidst War

In a country devastated by war, young men choose to follow Christ. Over the years, we have followed the story of a Bangui monastery turned refugee camp. Despite the ongoing conflict, something flourishes in the “periphery of the periphery of the world.”It seemed the war in the Central African Republic had ended. But that is not the case. The relatively peaceful situation in the capital, Bangui, can be misleading. In recent months, in the more remote regions of the country, rebel groups–whose identity and objectives are not always well-defined–have claimed hundreds of lives, burned down homes, and forced thousands of refugees to flee to surrounding cities and villages.

There is a risk of becoming accustomed to war, almost as if it were inevitable, as if it were the only way to live together... Instead, for those far away, the risk is forgetting about the war. Raise your hand if you remember anything about a conflict in this region, or if you even know the exact location of the country. The title chosen by JeanPierre Tuquoi, the former journalist for Le Monde, for his new book about the tormented history of this former French colony is not far from the truth: Oubangui-Chari, le pays qui n’existait pas (Ubangi-Chari, The Country That Did Not Exist Before). Though twice the size of Italy, it is a country that is rarely discussed in the media.

Then, in 2013, the latest in a series of coups caught the world’s attention. It was unlike any of the coups d’etat that had preceded it: it resembled an invasion by a foreign army. Among the rebels who seized power–a very diverse yet mostly Muslim coalition with the name Seleka–many were Sudanese and Chadian mercenaries. The new president, Michel Djotodia, could not establish order; there were raids and violence, and the national army was in shambles. Out of despair, a faction of the population formed aggressive vigilante groups (anti-bala-ka). Many in these groups were Christian, but the bishops were quick to distance themselves and to condemn the violence.

Later that year, on December 5th, the capital was attacked. In a matter of days, the country had become embittered. Months of constant war and people fleeing the violence followed. France intervened to prevent the conflict from becoming a genocide between Christians and Muslims. Djotodia was forced to resign and the National Assembly replaced him by electing a woman, Catherine Samba-Panza. The war rages on through more or less gruesome phases despite the deployment of a UN mission of 12,000 soldiers.

In November 2015–in the face of an overwhelmingly negative outlook for the country–Pope Francis decided to kick off the Jubilee Year of Mercy here. Shots were fired hours before his arrival, adding an element of uncertainty until the last minute. Yet, the visit went perfectly, and this was the first miracle. Bangui was declared the “Spiritual Capital of the World.” As the doors of the Cathedral opened, a new beginning was in sight. Second miracle: the fighting ceased. In March 2016, a new president, Faustin Toudéra, was elected. The elections ran smoothly, and no one challenged the results. Slowly, the refugees returned home. The country was on the road to recovery. But then, the country’s strength began to falter, and the rebels started committing violent acts once again. War is terrible but for an impoverished country like the Central African Republic, it is a death sentence.

Two facts express today’s dramatic situation. First, 80 percent of the country’s territory is still occupied, or in any case controlled, by the rebel groups: they decide the laws instead of the State, which is struggling to establish its presence, and is on the point of giving up. The election of the new president, the strong presence of the UN, and the copious assistance from the international community all seemed to indicate progress, but so far, the results have been disappointing.

The second important fact is that the latest UN report places the Central African Republic at the bottom (188th of 188) of the Human Development Index. We are the poorest country in the world. Meanwhile, the ground beneath our feet is rich in gold, petroleum, and diamonds. Our wood is in high demand in Central Africa, and agriculture, due to the climate and abundant rainfall, could be widely practiced and profitable. Let us not forget our youth, our greatest treasure: 50% of the population is under the age of 18. Yet, there is a widespread absence of the most basic infrastructure, and the roads, if they are not coping with one of countless soccer matches, are lined with crowds of unemployed youth, or youth selling items on a small scale... All await the new Central African Republic that seems ever so distant.

In the face of this desolate reality, there is no shortage of reasons to lose hope and give up. But it is pointless to continue to blame the enemy, who has never been truly identified, or to wait for someone to appear by magic to change the situation. This is the moment to start changing the situation, and for the people themselves to enact this change, in a great and long-awaited wave of love for themselves.

“On that 5th Of December...” Over the last three years, the story of our Carmelite community–living in the periphery of the periphery of the world, within a few kilometers of the battleground–has become intertwined with the story of this country and its capital. On that 5th of December, the day the war broke out, we began an unforgettable human and Christian journey, as intense as it was unexpected. In a matter of days, 10,000 refugees found safety within and around our monastery; the church was turned into a dormitory, the refectory into a hospital, the chapter house into a maternity ward, and my room into a medicine storage room. We thought it would only be for a few days, but these past three years have given us the opportunity to live the Gospel without setting a foot outside our home and without second thoughts... there was no time to think about it. There is no hero among us, we are just a small community of friars who did not want to give up.

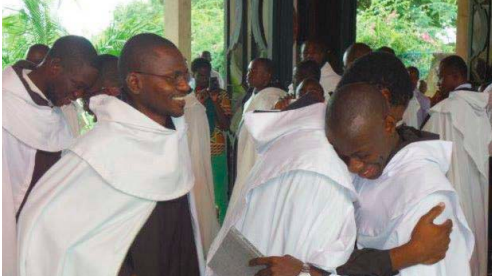

There were 12 of us, then, as the years went by, before we knew it, our community had grown. Today there are 20 members. I am the only Italian, but I admit that I hardly notice it, because our life together makes us one; it makes us one family. In September, seven young men entered the novitiate in our convent in Buoar, in the northern region of the country: among them is Aristide, the indefatigable nurse in our refugee camp, working night and day serving the sick, wounded, and expectant mothers. Thankfully, because some refugees have left, we will not have to hang a sign on the door of the convent that says: “We are sorry, but the maternity ward is at full occupancy...”

It is hard to believe that even while we were not far from the neighborhoods where the violence of war brought death and destruction, here at Carmel prayer never ceased, the sense of fraternity grew, and life thrived. Children were born in the refectory, while new friars were also “born” in the monastery.

A great honor. How is it possible that in a country decimated by war there are still young men who chose to follow Christ instead of leaving or, worse, enlisting in the rebel militia groups? Some may see it as a way of escaping suffering. This interpretation is not only false, but is offensive to Africans. If that were the case, there should be many more of us... given the large number of youth and the salary per-capita. Should a young man enter with less than honorable intentions, he would not be able to remain on this path. As a matter of fact, each vocation is a mystery that is not bound by human rules, calculations, and predictions. Could it be that these young people have experienced firsthand that only Christ can give them true peace in their hearts? That He is the only treasure worth spending one’s life for? And that those who choose to live the Gospel with their brothers can also participate in the development of the country?

A few weeks ago, we visited together the cemetery near Saint Paul des Rapides, the oldest church in the Central African Republic. It is undoubtedly one of the most sacred places in the country. It was here that, in 1894, the evangelization of the Ubangi-Chari region began through the courage and faith of a few French Spiritan missionaries. Starting in Brazzaville, they went along the Ubangi River and reached what was at the time a small village next to a colonial train station. Many of them perished at a young age, within a few months of arriving in this land, having fallen victim to tropical diseases. Their bodies lie in this cemetery, and their names are now covered by the layers of lime on the cement crosses of the graves.

As I reflected on these heroes of the past, I observed my young brothers. The heroes buried here would never have dared to imagine that their hard work would produce such a bountiful harvest. The “heroes in the making” above ground do not realize that they are the fruit of those seeds that, at about their same age, died so that the Central African Republic would come to know Christ. Of course, the fruit is not ripe yet; some will be able to break off from the tree and ripen elsewhere.

But it is still fruit nonetheless. I, an unworthy successor of those heroes, have had the unexpected blessing and great honor of observing the growth–without getting in the way too much, and growing myself as well–of the seed others sowed before me.