Fada... A De Oh!

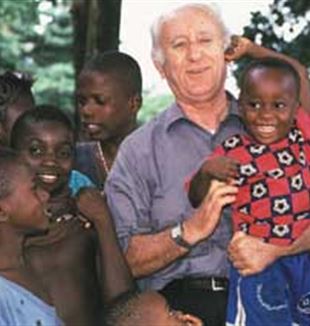

Fr Berton has written us from Sierra Leone. The horrors of the war, his kids and their need to start over again and to be welcomed.Dear Alberto,

I am writing to you from the idleness of Abidjan, where I have been for the past week, waiting for the flight to Freetown, on my way home. I have been busy, trying to put together the jumble of experiences lived in my two months of wandering around Italy, responding to the requests of the various communities that asked me for testimony about Sierra Leone, and in particular about the child soldiers. How I wish these poor victims of ten years of war were not called that! I wish they were not called that, because it stigmatizes them as actors rather than victims. I wish they were not called that, because it makes them enjoy a position of preference over their companions who have not fought, but who have suffered as much if not more than they, fleeing from one forest to another, living for years in refugee camps in the often fruitless search for their parents and relatives and bearing in their own bodies the mutilations they have undergone in a war of incomparable atrocity. I wish they were not called that, because it makes us forget the victims who have suffered most, who have suffered in silence, who have disappeared in silence, the girls, or better, the little girls, who are victims of sexual aberrations. They say that 60% of the kidnapped children are girls, but very few return, perhaps 30%, generously speaking. They return as mothers, when they could still be playing with dolls themselves. One in particular comes to my mind, who, when I see her (and by now two years have passed since she lost her child), it seems impossible to me that she was able to have a child, so young is she still, and what is more, frail. How many of them, after so much sacrifice, abuse, and suffering, have lost their child! Awa’s expression is still engraved on my heart. I had her photograph with me, the photo of her with her baby, the baby she lost. I thought I would give her pleasure by giving it to her. “Oh no! My baby!” was all she said as she averted her glance with a tear. These are the ones we forget about easily, when our attention is riveted by the little “Rambos.” And what is worse, because, viewed as little combatants rather than victims of the war, they have been treated as combatants and as such feared, imprisoned, mistreated. This was the case with thirteen of them. I’ll tell you the story.

A group of thirteen

I came to find out, and I came to find it out late, too late, that thirteen boys, sixteen-year-olds except for one who was thirteen, had been put in prison, and what is more, in the central prison where all the worst things imaginable were, and it was already six months that they were there. The Red Cross had tried to do something. Unicef had tried to do something. The Ministry of Social Services had tried to do something, but the boys were still in jail. I had become friends with the Minister of Justice who, ever since the “good times” when I was serving as prison chaplain, had helped me a great deal to straighten out cases of young prisoners who had ended up there because there was no place else that could take them, such as a juvenile prison. He intervened immediately, but it took a good week before the peremptory order for immediate release was carried out… and why? Because everyone was afraid of them, and to tell the truth, the thirteen young jailbirds had not shown themselves to be too malleable in prison. I have to say that the boys had been treated well. From everything I heard and saw when I went to pick them up, the boys had not only been treated well, but relations with the wardens seemed cordial, if not humanly pleasant and joking. The thought had even passed through my mind, “Why should I take this on myself?”… but prison is still prison, and the thirteen couldn’t wait to put it behind them. In private, I was told, “They’re criminals. Watch out! You won’t be able to keep them with you for a week. At the first chance, they’ll pick up their weapons again. I would not take on this responsibility.”

The ground seemed to be giving way beneath my feet, but then I looked at them again, those thirteen boys, and I did not see any difference between them and the hundreds of their companions with whom I have already dealt, and some statistics ran through my mind: out of 2,500, only five had gone away without saying goodbye. St Michael’s [where the boys were later taken in] was not surrounded by walls, it had no guards, not even a policeman to keep even a little bit of public order whenever we might have to face an emergency (and, believe me, we have had emergencies), but only family homes and good people, with no special training, to hold them. The others had stayed; these would stay too. So I took them. One of them said, “I have a house, I sleep in a house!” and joy sprang from his eyes. Who knows how much he had lived in a forest. And the other? He was as tall as his mother, and when she came to get him all she could do was cry and look him up and down, remembering how small he had been when she lost him. Little Hassan… how much road he had traveled by himself, from one forest to the other, hanging on to whoever was a little taller than he, until he reached Guinea to live as a refugee. “Johnny comes marching home!”

Abdul’s pail

But this is not the end of the story. Johnny is deeply wounded, because Johnny has seen nothing but violence. He was born in violence. He grew up in violence. He is smeared with violence. Johnny needs a long time to heal from the wounds that go to the depths of his heart, and people are in a hurry, they expect Johnny to get right back to normal, but Johnny can’t, and it is always his fault if he can’t. When he explodes, because he has always done things in a hurry, because before it was enough for him to point the barrel of a gun to end things, to be right, to get what he wanted, but now things have changed and Johnny is not yet used to it, and so he explodes and he gets thrown up in his face everything that he would like to forget, a whole past that has made him suffer. He hears it thrown in his face with a banal insult, “Rebel!” … “Sure! What do you expect from a rebel.” Johnny’s heart starts to swell, his throat shuts tight. Right! Shut tight to whom?

The boys come back. They come back to see us to reassure themselves that they are still ours. They do not want to feel alone in front of a world that every so often becomes hostile again.

Poor Abdul. It fell to him to go fill up the pail at the fountain. It had to happen to him, who was so calm, pacific, doing well in school.

He was there watching the pail fill with water, his eyes enchanted by the rising level, and was waiting patiently, when someone knocked his pail away. A girl his age, just look at the cheek of that girl… and the blood rose to Abdul’s head. “Oh no!” and he put the pail back where it had been. She pushed, he didn’t yield, she taunted him, “Rebel!” and nerves reached the snapping point. The girl’s mother intervened, and instead of being a mother to both of them, she too said “Rebel!” The two got in a scuffle, she pressed charges, and he ended up in prison.

He only spent one night there, but that was enough to throw him into crisis. The good sense of a judge gave him back to us, saying, “You really want to destroy this boy! He has just begun picking up again after a life as a prisoner… and you condemn him once again”!

He got out, but the trial lasted a couple of months and cost us a lot.

Coming back home from the city, the traffic was so intense that I had to stop numerous times, and during one of my stops a voice came through my car window: “Fada… A de oh!” In the pitch blackness, I recognized him. He was one of the many boys that we had settled in the city here and there with craftsmen of good will: carpenters, auto body shops, mechanics, tailors. It was an expression meant to tell me, “I’m still around. Don’t forget me!”

Who can ever forget them? Who can ever forget Mosquito Black, who, out of rage, a knife in his hand to get revenge on an assistant, had broken a window? How he has changed! Who can forget Fatumata, who ran away from home and came to seek refuge with us, her head swollen, her eyes popping out of their sockets, from the beatings by her crazed husband? Who can forget Isha, with his patrician behavior, but always broke?

Who can ever forget them?!

Remembering all of you,

Fr Bepi Berton