Horowitz: The warmth of a jingle

In his studios, among a swarm of musicians, "creating the New York soundtrack". His story, his encounters, his words. This is how a friend recounted David Horowitz’s story in a book published a few years ago.Years ago, when I lived and worked in New York, I often visited the DHMA (David Horowitz Music Associates) offices, at 373 Park Avenue. The association occupied the entire second floor of a beautiful office building in one of the most interesting areas of the city. The front door was flanked by the usual colorful array of New York food and services: pizza by the slice, a Korean deli, the Dos Caninos restaurant, the Giraffe Hotel, a ladies' nail polish shop. Up on the second floor, in the DHMA recording studios, you were welcomed by a team of musicians and creatives who helped create, day after day, the New York soundtrack. He was the soul of it all, a kind man named David Horowitz. I had dedicated a few pages of a book I wrote in 2004, “Sotto il cielo d’America” (Under the American Sky), to him, in a chapter where I recounted the story of his colleague and friend, Jonathan Fields.

Now that David has left us, torn from his loved ones by the damned coronavirus, I thought it would be nice to remember him through the words he entrusted to me at the time, and which I quote in this excerpt from my book.

PARK AVENUE, THE WARMTH OF A JINGLE

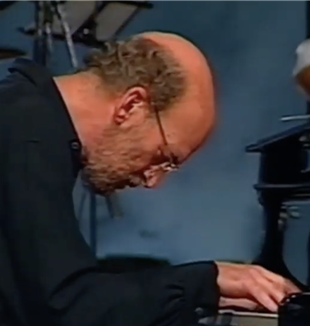

(...) David Horowitz's office at DHMA has the warm and embracing atmosphere of his music. The walls are covered with plaques that tell of a career at the very top. There are countless Clio Awards, the Oscars of advertising, along with a gold record for the five hundred thousand copies of Sesame Street Fever, and awards received by famous clients. There is also a painting by William Congdon, the American artist who, for several years, lived a stone's throw away from Fr. Giussani, and clearly visible, framed, the cover of Traces, the CL magazine, dedicated to Horowitz and his band after their inaugural concert at the Rimini Meeting in 1998.

David is one of those musicians who, in thirty seconds or in a minute, with a few notes, can transmit a whole range of emotions. “Music, for me," he explains, "is the most direct way in which one heart can speak to another.” This is demonstrated by the commercials for which he provided the soundtrack. In 2003, American television was bombarded by a New York Stock Exchange commercial, accompanied by the words of former mayor Rudolph Giuliani and majestic notes, which seemed to convey the key messages of the American way of life: freedom, courage, the desire to dream, tenacity. Needless to say, they were signed by Horowitz. Furthermore, in 2003, Campbell, the canned soup company turned into works of art by Andy Warhol, asked David for music for tomato sauce with a familiar target audience, asking him to compose something before even one scene of the commercial had been shot. The instructions given to DHMA by Young & Rubicam, an advertising giant, was to promote, within thirty seconds of music, a message that spoke about traditional family values. When David's music commercial began to air on television, Campbell received a wave of calls from across America, from people who wanted to know “where to find the CD” from which the music was taken, because they absolutely wanted to used it at weddings and on special occasions…

"I remember perfectly Jonathan's crisis and his conversion,” says David, sitting in his creative corner between electronic keyboards, a plasma screen computer and some plants, “and I remember the moment he discovered CL. All I knew at the time was that he had encountered something, but I did not know what. What was immediately obvious to me was that this "something" was helping him concentrate, to start again. Then when I met the people who were close to him, I realized: for the first time, he was with people who looked at him in a different way than he had ever experienced before.”

Through Jonathan, David also came face to face with the experience of the group born from the charism of Fr. Giussani. It was undoubtedly a reality far removed from the one that accompanied Horowitz's life and career.

Like Jonathan, David came from a New York Jewish background. Since he was three years old, music had entered his life, never to leave again, even if traditional music teaching, all patience and music theory, was not suited to little Horowitz, who loved to play by ear. So he fell in love with jazz. "It is music that is aesthetic, it is freedom, it is improvisation, and I am an improviser. I have always been a lousy piano student, because I liked to "embellish" the things my teacher asked me to play. After several teachers, I quit, I learned by myself, and then, at college, I formed my own jazz group. It was called the "David Horowitz Quintet" or sextet or quartet, depending on how many people there were at the time to play…” It was the sixties and David lived in one of the most creative and crazy places on planet Earth, the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

"That environment changed me, I went from the protective Jewish reality of Brooklyn, to a world where anything could happen, and not just musically. It was extremely exciting, there were always millions of things: music, painting, culture, “off-off-off-Broadway shows.” You could not walk a block without running into a musician or a famous artist. Everybody had their "thing", everybody was chasing their "thing", convinced they had the key to change the art world. In a somewhat chaotic way, it was a community, where the common dream was to "go Uptown", to break through." David also immersed himself in literature and began gradually to narrow down his musical preferences: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, and Thelonius Monk, above all others. Performances with Gil Evans and Tony Williams, a job as a composer at the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., arrangements for albums by Peter Allen, Carol Hall, and others.

And then success in the advertising world with his wife Jan, whose office at DHMA, the company’s organizational epicenter on Park Avenue, is adorned with Indian memorabilia in honor of her western origins (Jan is from Colorado). Gradually, David was joined by artists such as Ed Walsh, who can write on his resume that he toured with John Lennon, Madonna, Diana Ross and Simon & Garfunkel. And then Ben, Joe, Ted, Bruce. And Jack Cavari, who toured with Frank Sinatra and Aretha Franklin.

Definitely, a competitive environment. "The movement," says Jonathan, "has also helped me to cope with the difficulties of this competition. In the end, recognizing my weaknesses, my poverty, I was able to ask. It was the beginning of the great education of the movement in my life: to recognize that I am dependent and in need. I asked for help, without problems: to install a new keyboard or to keep up with new technologies. Little by little, miraculously, things began to change. We became friends, in a world where it's so difficult to be friends."

A journey that Jonathan made alongside Maurizio "Riro" Maniscalco, who became an irreplaceable presence in his life after a mutual fondness developed, almost by chance, after playing Simon & Garfunkel songs together.

Jonathan's encounter with CL left its mark upon the DHMA microcosm, in a reality of strong artistic individualities. But, first and foremost, it left its mark upon Horowitz.

"After Jonathan has been seeing these new friends for some time,” says David, “he gave me a copy of Fr. Giussani’s Religious Sense. It was the first English version, I was absolutely captivated, fascinated. Then Jonathan introduced me to Riro, who invited me to talk about myself and my work at the Rimini Meeting in 1997. I immediately said yes, because of the book and what was happening in Jonathan's life. Preparing that testimony forced me to come to terms with my life. I wondered what people might think of someone who writes music for commercials. But I then began to realize that much of the music I wrote had its own life, its own value. I think it was the effect of the way Giussani had introduced me to the idea of judging the way one confronted their work. I have always been struck by the way he viewed work as a decisive part of human experience and the definition of the person. Before and after that testimony, I began to think about my work in a different way, to recognize that I was creating something that was not there before, and that it could have a meaning that went beyond the commercial purpose of that music. Now I understand better that it has meaning because it comes from me, because it is the expression of who I am.”

His first experience of the Meeting and Riro’s friendly insistence led David to immediately say yes again when, the following year, he was invited to play the opening concert at the Meeting, together with the DHMA band. "I did not know what I was getting myself into! For months, and until the moment I got on the plane to go to Italy, I worked like crazy, because I had absolutely no material ready for a two-hour concert." The rediscovery of the aesthetic value of his music, however, had made David so reckless that he agreed to go back to his origins, to the time when he was leading a band, and not a jingle company for multinationals.

"There were thousands of people listening to us. We threw ourselves into it. I think I talked more than I played. It was a great experience."

Over the years, David became a regular presence at the Meeting. And his relationship with his Italian friends and with the movement also resulted in a meeting with Fr. Giussani. "We looked at each other for a moment, greeted each other and immediately I felt that I had known him my whole life. Amazing: I was completely at ease, we talked for an hour about a lot of things, particularly about the relations between Judaism and Christianity."

Horowitz admires Fr. Giussani, among other things, because of the historical role he assigns to the Jews. "Within the movement, I never felt as if I were an outsider, or something to show-off: the Jew to show-off in public. Some Jewish friends of mine tried to warn me: "How can you be with these people, with Catholics? Can you not see they want to use you?" I always replied that the interest, understanding and compassion that I had encountered were completely genuine. And I am very sensitive about these things."

David regrets having drifted away from religious experience in his youth, after his bar mitzvah. He is not practising, he only goes to synagogue - he says - for weddings and funerals. "Yet, every time I go there, I am very impressed and I do not know why. My relationship with the movement, reading Giussani's books, helped me to look up, to make me want things I had not done for a long time. One day, I took a volume from my library and began reading: "In the beginning was the Word..."I immersed myself, I read everything in three different translations, to make sure I was reading the right things. It was one of those wishes that comes to you when you see someone bigger than you, more alive than you.”

Stopping by Horowitz's studio, you can hear the notes of other creatives at work at DHMA spreading through the corridors. They could keep the doors closed and isolate themselves, waiting to all get together in the recording studio. But it is as if what has happened over the years to the small group of artists working on Park Avenue has made the need to communicate unavoidable. The pieces of music floating in the air are a form of dialogue between friends.

(...) At DHMA, not even David, the former Lower East Side boy, who grew up on bread and jazz, and with the dream of "going Uptown", after the experiences of these years, intent on letting cynicism bury everything. "There are times when you compose music thinking only of the deadline that clients have given you. But if I sit down and think about it, I cannot help but recognize that behind my music there is a mysterious mechanism that makes me capture something that is in the air, to make it happen. It is the beauty of the creative act of something that was not there before. But it is becoming clearer and clearer to me that it already existed. Art puts us momentarily closer to the initial Act, with a capital letter, creation. You have to reach it, open yourself to it, otherwise work is just a job, while instead it is what I am made of, something which I have understood better thanks to Giussani. Someone asked Beethoven where his notes came from and he answered: "I have no idea, I just trust in Providence". I have spent many years keeping reality out of my door. But ever since I met all these crazy CL people... well, at first, I was a little disoriented, to be honest. But then I realized that there is so much greatness outside my door, so much life, enthusiasm, desire to engage. It has helped me to have a greater perspective, to feel more connected to everything."

And to cope with the creative rush, it was not always easy to compose music for a commercial intended for the interval between two football games on TV, David Horowitz started writing poetry.

*Journalist and Director of External Communications at ENI*