God gave us two books

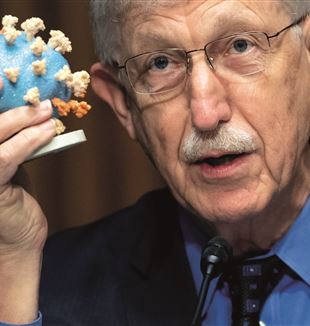

A scientific advisor to the White House, he led one of the most groundbreaking adventures in genetics. And he is among the leading figures in the fight against COVID-19. We met him at the New York Encounter, where he told us about his search for truth.Francis Collins is a tall, thin gentleman with white hair and a mustache. His eyes are blue. We shook his hand, and thought about the fact that we were meeting one of the most important men in the US during the months of the pandemic. Indeed, until last November he was the head of the National Institutes of Health, America’s medical research agency. He was chosen by Barack Obama and retained by both Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Just to be clear: Dr. Anthony Fauci was his subordinate. Last month, he was appointed scientific advisor to the White House. In addition to being a man of institutions, he is above all a man of science. He led one of the most important and groundbreaking adventures in genetics–the Human Genome Project, which involved the mapping of the human genome and which has contributed to much of the knowledge we have about how our body’s DNA works.

We met him at the Metropolitan Pavilion where the New York Encounter was taking place. He had been invited to the NYE to dialogue with New York Times columnist David Brooks. An evangelical Christian, he missed no opportunity to talk about how, as a scientist, he embraces faith without rejecting the scientific method. He was an atheist in his 20s, but after his first few months at medical school and working on hospital wards, grappling with suffering and death, he realized he had never thought about the question of God. “After a couple of years of struggling and trying to understand whether I could actually accept the idea of God, and then ultimately deciding what kind of God, to my surprise I became a Christian.” By then, however, he was a physician and scientist. “People around me thought I would go crazy trying to reconcile faith and my profession. So far, that has not happened.”

Why do you think you have been able to reconcile faith and science?

Science is the way we understand how nature works. It involves an incredibly powerful method. But there are questions that science cannot really help us with. What happened before the universe began? Why am I here? What happens after we die? Even though science is at the moment silent on all of these really interesting questions, I still want to ask them. As long as you are careful about which kind of question you are asking, there is no conflict between being a believer and a rigorous scientist. Francis Bacon gave us a wonderful metaphor: God gave us two books, that of the word of God, which is the Bible–which I read almost every day–and the book of God’s works, which is nature, and which as a scientist I get to work on every day. They are both God’s books, so if somehow we think there is a conflict, we may have misread one or both of them and we have to go back to figure out what we have not understood. Not everyone thinks that way. So we do have a bit of a cultural clash. Right now, it is made infinitely worse by the way in which we have divided ourselves into separate tribes. In our country, for reasons that are utterly irrational, science seems to have been embraced more by the left and faith more by the right. Does that make sense? Politics has infected everything.

Even positions with respect to the pandemic?

Experts thought that it would take years to produce a vaccine. It took us 11 months, and millions of lives have been saved as a result. But it is also really troubling that there are so many people who still reject it. In the US, this is about 50 million people. They have heard stories, conspiracies, and misinformation that makes them afraid there might be something wrong here.

What does this mean?

It is a terrible indictment of the really destructive nature of the kind of tribalism I was talking about earlier. There are people who are shamelessly distributing information that is demonstrably false. In the meantime, people are dying because they are not vaccinated. You are saying this as a scientist.

But what about as a man of faith?

I am sorry to say this, but people of faith have also gotten pulled into these lies that are demonizing science. The group that is most resistant to vaccines in the US

are Christians, white, evangelical. And I am Christian, white, and evangelical. It is heartbreaking to see that it has come to that.

Does this have to do with the use of reason?

I was once naïve enough to think that if you put the objective facts in front of somebody, he or she would always make a rational decision–that reason would always rise to the top. David

Hume says instead that reason is a slave to the passions. And our polarized society, with all of the ways that information has been weaponized, has inflamed everybody’s passions, causing injury to our ability to use the tools of reason.

How do you know this?

People do not accept information that does not jibe with the current stance of their tribal group. This is called “cognitive bias.”

What does that mean?

If you try to tell me something that is actually true, but does not fit within the framework that I am currently adhering to, I am going to say that it must not be right. I might bring on board something completely fraudulent if it happens to resonate with my current framework. And we get deeper and deeper into this dynamic.

You were the head of the National Institutes of Health for 12 years. What was the hardest moment for you?

A lot of it was exhilarating. I had the opportunity to lead the largest medical research agency in the world. We started new programs on cancer immunotherapy, tried to figure out how the brain works, came up with solutions for rare diseases, and much more. The hardest challenge was COVID. We had to make sure we were bringing every possible kind of scientific resource together to address it without a single day being wasted. My job was to convince industry, academic institutions, and the government to all get together. It was amazing how successful that was, but it took longer than everybody wanted. We got to the point of what I thought was going to be an amazing success story, only to have a lot of people say, “I do not want the vaccine.” That I was not expecting.

You were also the villain in certain conspiracy theories. What helped you face these attacks?

Prayer. If I receive criticism that I deserve, I figure out what I can do better. But if the accusation (as it was actually put forth) is that I work with Bill Gates to put chips into syringes, I feel bad for the people who are propagating this. They are obviously very mixed up and confused. I think that most people are good and well-intentioned and trying to figure out what to do at a scary time, but some conspiracies that have no basis are putting people’s lives at risk.

Is it possible to oppose polarization?

There is a group here in the U.S. called Braver Angels working to bring together people from the opposing tribes, the so-called “reds” and “blues,” the right and left, and for a couple of hours encourage them to actually talk to each other: no insults, no personal attacks, but explaining why they feel the way they do. And the other group has to listen and explain why they feel like they do. Every time at the end of these two hours, they ask people confidentially what they have learned from it. And almost everybody replies: “I found out we were not that different after all.” That gives me hope because, underneath it all, people still care about basic things: faith, family, freedom, love, beauty, truth, goodness. Those pillars that we are building our foundations on, those are rock solid. So we pile on top of that all this other not-very attractive architecture that gets in the way of recognizing how similar we really are. We need to get more of these encounters to happen. They obviously cannot be recreated on a large scale because these events happen really intimately. But that is what we need more of.

You recently spoke of your friendship with the polemicist Christopher Hitchens, who often said that “religion poisons everything.” What did you learn from that friendship?

The first time we met I asked him whether a strict atheist like him could claim any real importance for good and evil, or whether they should be regarded as artifacts of natural selection, of no real significance. He called the question “dumb” and did not answer. Yet, I had the impression that he was an interesting person. I think we are all enhanced by talking to people who are really saying things very differently. So gradually over a few more interactions we got to know each other and became friends. He then fell ill and I helped him find his way through some clinical trials, which I think gave him an extra six or twelve months to live. By the end, I felt he was somebody I had a very warm and loving relationship with, even though in the world’s view we were on opposite poles of this question of faith.

Read also - Nothing human is alien to us

But if friendship is not about agreeing, what is it about?

It is to gain some kind of a personal revelation about yourself through another person, without being so defensive that you are hiding who you really are, and being enriched by that gift even if it involves a challenge to some of the things you hold dear. It was like that with Hitchens. When we were not talking about faith, I listened to him speak about American history, or his favorite author, George Orwell. I learned a lot from him and I am grateful. I seek out these opportunities. I know another atheist: Richard Dawkins. We are often invited to public debates to represent opposing sides. It is always a pleasure to debate with him. I have known him for almost 20 years now and whenever I go to Oxford I always ask if he is around.

Both faith and science are a longing for truth. What is the most powerful driver for you?

This is difficult to answer. They are different questions, they hit different parts of who I am. I had two years of intensely searching whether a God existed and if so, asking if He cared about me. Then I discovered the person of Jesus, who I had assumed all along was a myth, but I then found out that there was more historical evidence for Jesus–and for his Resurrection–than I had imagined. I still have doubts about various aspects of my faith, particularly when a terrible crisis happens: How does a loving God allow suffering? We seek God’s answers in moments of struggle, of searching for truth. The search for truth carried out in my laboratory is not far off from that. When a scientist discovers something for the first time–I have had that experience a few times–it is not just a scientific achievement, but it is also a glimpse into God’s mind. It is a moment of worship. Being in the laboratory is like being in a cathedral; they are both places where you can glimpse the Almighty. In a different way, but it is all really the same thing.

Who is the person of Jesus for you?

Jesus is both God and human. Jesus is the way in which I, with all my imperfections and all the bad things I do, can get closer to God. By His sacrifice, I am saved. When I was a kid, I did not have a clue what it meant when I heard Christians say that. Now it is the most incredible truth that I believe in. Jesus is that relationship that I have always longed for, without knowing it. When I come across the pain of someone I care about, I want to say to God, “Why are you letting this happen, do you not realize…?” Then I stop and think, “Yes, you do realize, you have suffered more than I will ever know.”