The miracle of existing

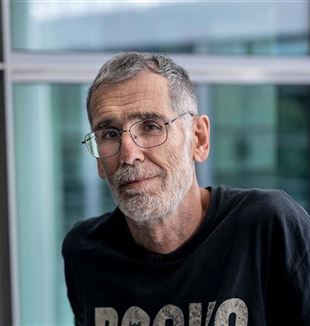

“Every city should be like this place.” Juan José Gómez Cadenas, a Spanish physicist, spoke at the Meeting of Rimini about himself and his questions. “Why are we here? What is all this that is never enough for me?” From October Traces.The issue is simple. “What we see, touch, and observe never cease trying to amaze and move us.” Juan José Gómez Cadenas, a 61-year old Spanish physicist, directs the NEXT experiment on neutrinos at the LSC, the Canfranc underground laboratory in the Spanish Pyrenees. Cadenas has worked all over the world, from the US to Japan, including at CERN in Geneva, to advance his studies in particle physics. “In fact, I work on the origin of the universe,” he said at the beginning of his talk at the Meeting of Rimini, “the reason all of reality exists.” It was not difficult to spot him among the stands, observing with curiosity and surprise something he did not expect to find. “It was a shock when I arrived here. I thought right away, ‘My goodness, these are Christians, but they’re not here lighting candles.’” He talks about exhibits and encounters with people from all over the world and of many religions. “It’s a place where you can talk about art, cinema, and physics, about everything.” Full of interesting people, he adds–“especially the young people, all of them smiling. It’s like a village where people are more happy than sad. They’re more affable, more open. And so I think, ‘Every city should be like this place.’ Everyone should see this Meeting that offers itself to the world as an alternative or a complement to the life of each person. It’s as if to say, look, it’s better to come to an exhibit, speak with people, eat together, and then go hear a talk about the brain rather than staying glued to social networks….” He came to Rimini because of an invitation from some friends and colleagues of the Movement he’d met over the years. “People who, meeting me just as I am, proposed that I journey a stretch of the road together with them. Just like what happens at the Meeting. I wish everyone could meet something of the kind.”

So, who is Juan José Gómez Cadenas? We know you as an internationally renowned physicist…

It’s difficult to define oneself. Certainly I’m a scientist, but that’s not all. I love literature, too, and I’ve written a few novels, a bit for fun. But in order to write, first of all you have to be a passionate reader. I have read and read a great deal ever since I was young. The third factor is that I’m the father of two children, Irene and Hector, and the husband of my wife. This defnes me totally: family, science, and literature. And I’d add my passion for languages, which arose from my love of literature.

And physics? What was the origin of your interest?

I don’t know. It’s odd, but I don’t know. Perhaps it was the same sensation of surprise and fascination that fed my passion for literature. The point of departure is the same; it’s the same disproportion and to go into things more deeply.

That is?

My father was career military and we moved often. I was little and every time we arrived in a new place it was exciting. There were many opportunities to meet people, but also a fear of being alone. This moves you; it fills you with questions and doesn’t allow you to be placid. And with all the new things you encounter, you feel the need to explain them to yourself, so I read books and learned languages. This is the similarity between literature and physics–they dig into different aspects of reality but start from the same inquietude. “Why are we here? What is all this that is never enough for me and consumes me inside?”

So then, the origin is wonder.

And the need to find meaning in the face of what you see. When I was little, this happened through literature. Physics probably “arrived” when I discovered that the world that fascinated me so much could be measured, quantified, and understood. I was in high school when I began to realize, thanks to a teacher, that everything is ordered. What a wonder! And in pursuing this and arriving at quantum physics, I understood that it’s true that the universe is measurable and understandable, but that it’s equally full of mystery, of things we can’t explain. Physics comes as an attempt to explain, as a search for the meaning you perceive.

But if in science there remains mystery, can it be a good road for finding that “meaning”?

Meaning does not mean certainty: “I’ve understood everything! Now we can go.” Rather, it’s a matter of saying that there’s some certainty in my uncertainty. It doesn’t lessen you to say that you don’t know something. In history, every time we thought we understood everything, something unhinged our convictions. Think of the Greeks, who realized that the skies have an order and don’t just follow the whims of the gods. Or Galileo. Or in more modern times, the discovery of the quantum nature of the universe, which is more mysterious than we had thought. The more steps forward we take, the more we discover that there are more things we don’t know. This is anything but considering the case closed. I want to continue finding something that drives me further on. This is science. The more you progress, the wider the prospect of mystery that opens out.

What is this mystery for you? Is it connected with faith?

Often the idea of faith is reduced. Personally, I don’t believe in God, but neither do I define myself as anatheist. I’m someone who observes, looks, doubts, examines, and says, “This is interesting. I don’t understand this yet. Let’s see what’s behind it.” Does God exist because He has spoken with me? It scares me to say this. But it also sounds strange to say that God doesn’t exist. For me, it would be stupid to think of believers as crazy. They see a part of reality that I don’t see. I haven’t had a revelation like they have, but precisely for this reason we have a lot to look at together and compare ideas on. This holds also for those who deny the existence of God. As a physicist, I have faith in science. I have to have it in order to be a scientist, otherwise it doesn’t work. I must have faith in science and in human beings because this is the only way to move, to go forward, to take steps.

What do you mean by “faith in human beings”?

You don’t need to be religious to understand what I am saying, even if they tell me it’s something deeply Christian. But I think it’s human, first of all. I think of giving and receiving. In my life, I’ve always tried to give, at home, at work, and with my friends, without expecting it to be reciprocated right away and without calculating, and it has always worked. My family is the best thing that’s ever happened to me; my children are a miracle. And then my friends… Sometimes things don’t work out right, but more often that hundredfold the Bible speaks of is can be experienced. Even if we are all imperfect, and not as free as we would like, in the end, the factor in life that defines us is, Do you have hope or not? I do, and mine is in human beings. Where does it come from? I don’t know. For me, it’s one of many mysteries. How can all this be defined as anything other than faith?

Human beings are imperfect, yet capable of wonder and hope. Do you think human are made well or badly?

There’s a Spanish poet, Blas de Otero, who speaks of the human being as “an angel with great wings of chains.” We’re imperfect, but there’s something in us that’s absolutely saviable. Human beings are fallen angels who want to fly but can’t manage to. However, there’s hope, and the ability to be a bit better each time. The history of humanity shows an evolution in the quality of feelings, the way we look at human dignity, children, women, rights. Certainly, maybe it’s not all beautiful the way we would want, with many steps backwards, but the general drift, the tendency, is positive. For Christians, God made us in His image. I think we come from the mud but we see an angel, a “god” that perhaps we invented and we want to be like him. We’re not perfect in anything but we aspire to be so. My faith is based on this aspiration, this possibility. I speak again of my children, but they are the brightest example of this, a daily experience of it. Faith needs material things. I’m not a person who can believe by engaging in abstraction. I have the good fortune that every day I wake up and I see in them a demonstration that human beings have a future, a hope.

Why?

Because they’re there, because I see them grow and “evolve.” Because my son comes to me and says to me, “Dad, today I read a book by such and such a philosopher.” Or my daughter, who hopes to become a doctor, who tells me that she learned something new giving emergency medical help to someone while she was out shopping. Well, in those moments I feel that the universe becomes a lovable place. For this reason, hope is not an abstraction. Human contact, another person, something concrete, is needed. A miracle.

And for you, what does it mean to be the object of these miracles, to become conscious of them? You said that among the various things that move you, there is the fact that in the history of the universe, human beings occupy a microscopic portion of space and time, yet it is precisely in human beings that an awareness of everything happens.

On this point, there’s an analogy with what I study, neutrinos. You can imagine the neutrino as the most insignificant thing in the universe: it doesn’t interact with anything, it’s everywhere, nobody pays any attention to it. Or you can take into consideration the hypothesis (what I’m working on) that the origin of the universe as we know it lies in the neutrino. You can imagine the same thing for human beings. You can take the nihilistic position and say that nothing has meaning, that human beings don’t count for anything, that they are part of an insignificant species in an insignificant world, and so on. Or you can look at the probability that you and I are here, now, speaking: if the point of view is the history of the universe with all the variables in play, the probability is zero. But then why are we here? It’s a miracle. A miracle of God? I don’t know, I don’t think so. But I feel incredibly fortunate.

What does it mean to hope, if, as you have stated on other occasions, there’s nothing before life or after death?

It’s true, I think so. But this doesn’t frighten me. I did not exist before, and I will not exist later. But I’m here now and I’m observing an inconceivable miracle. If we are the object of this miracle, if we are capable of seeing it and understanding it, then our responsibility is not to pretend that we don’t see it. You can say that God exists or that He doesn’t, but if the whole universe happened, and if it has happened that we exist as we are, that we can understand it, that we can interact in this way among ourselves, feel the love we feel or eat a sandwich with pleasure, we can’t look at these things without being amazed and moved. Whether you say it’s God or not, the point is that the miracle is the same. Reality is reality.

So the point is to allow yourself to be surprised?

This happens to me constantly. If two days go by without it happening, I think I must be sick. You know those sensations that take your breath away? The “wow?” They happen for me in front of my children, but also during a walk in the fields with my wife, seeing the marvelous blue sky, or swimming in the pool. Simple things, little things. Or in front of what you’re doing in the laboratory, when you realize that the thing you’re working on exists and isn’t a simulation or an abstract theory. The first miracle is that things exist, that you exist. If you have your eyes open, the miracle of being alive is evident. The Catalan poet Jaime Gil de Biedma says that “the fact of being alive asks something.” I’ll take that a step further: not the fact, but the miracle of being alive. You can’t help but feel gratitude. I’m full of gratitude, and it doesn’t allow me to remain tranquil or passive.

I’m listening to you, and it’s hard not to think that Christianity exalts exactly this humanity that you describe.

This is a very interesting point. What impresses me about the figure, I wouldn’t know whether to say literary or historical, of Jesus, is that He is a man. My family, like everyone in Spain, was Christian. I’ve read the entire Bible. When I was little, I liked the Old Testament a lot; it is full of compelling stories. The Gospels bored me. I didn’t understand anything about this guy who spoke in parables. When I was seventeen and Jesus Christ Superstar came out, I began to explore and read various authors who spoke about Him. The more I read, the more He interested me. But who was Jesus Christ, truly? What did He say? Out of everything, the thing that attracted me the most was His compassion. For me, the most crucial passage of His life was the episode of the widow of Nain: “Woman, do not weep.”

Why?

I see myself in her place in front of that man who shows us another way of conceiving of life, one that is more beautiful, more good, a different horizon. And whether we like it or not, this way of conceiving of life has shaped our way of living today, at least in the West. Our whole civilization starts from Christianity, even though there are also dark moments in the history of the church. Today, just as children rebel against their parents, many people try to deny its influence, but it’s impossible. If tomorrow some extraterrestrials arrived, they would see our wars, all the social injustice, the fact that we’re devastating our planet, our evil, and they would ask, “Why shouldn’t we destroy them?” Then they would see our cathedrals. “It’s an ugly species, but look what they can make.” They would spare us.

What do you mean?

Our society is obsessed by the affirmation of the ego, the value of the individual. I, too, care about this. I, too, want to succeed in what I do and be acknowledged, but this isn’t enough for me. It’s not enough to be a great physicist, an excellent husband and father. I’m someone who’s working on a great “cathedral,” a bigger building. Not a pyramid–that is for the pharaoh. In the cathedrals there is a different sense, a sense of a community that is in relationship with something bigger than itself. For some, they were built for God. For others, like me, they can signify the striving for the all. In a story by Asimov, a machine recognizes the existence of God when human beings reach the apex of knowledge. Thus, God can exist or be only an aspiration, as He is for me, but in a certain sense, what’s the difference? In both cases it’s not possible to resign yourself to being a banal accident without a future. Deep down, banality is another way of expressing a lack of hope. Christianity combats banality. For this reason, I find many friends among Christians.