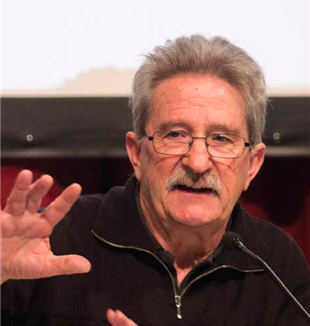

"I'm Struck by the Smiles of People Who've Come Back to Life"

Mikel Azurmendi, philosopher and anthropologist, offers a secular outlook that has, however, been forged by awareness of the most urgent markers of the time we live in: immigration, nationalism, Jihadism, and the value of religion in the public sphere.Mikel Azurmendi is 75. The Basque philosopher and anthropologist offers somewhat of a secular outlook, but one that has been forged by taking into consideration the most urgent markers of the time we live in, especially immigration, nationalism, Jihadism, and the value of religious experience in the public sphere. Two years ago, while presenting Julián Carrón’s book "Disarming Beauty" in Madrid, Azurmendi, an agnostic, described his surprise at meeting people who lived a Christianity that was “different from what I myself had lived.”

He said he had intuited “a passage from a set of rules and sins to a ‘law of meaning,’ in which only one thing was obligatory: searching for the meaning.” He came to this understanding in a world like ours, where what is “most needed,” he said, “is an escape from ideology. And entering into the ‘you.’”

If you had to describe the social and cultural situation the West is in at the beginning of this century, what words would you use?

At the social level, I think we have seen the triumph of the most possessive and solipsistic form of individualism, in which the other has nothing to do with me, or interests me only as a place to take out my anger. At the cultural level, throughout the 20th century we watched a slow but progressive decline in our sense of meaning in life and now, in the 21st century, we’re running straight toward nihilism. Everything can be bought and sold, even a Master’s degree in law. There’s a complete ignorance of the good. And evil? It doesn’t exist. The “I” is equated with the pure “right to choose”; the individual is the one who can decide about everything, no matter who he is and who others are. He has the “right” to do and say whatever he feels like (because “your truth is no truer than mine”). We think we are the masters of life and death. Existing together with this overwhelming majority of the population, there are a few small groups of people who live a life that’s split between a bookish bubble of academicism (the “lukewarm fanatics” of reason, engaged in purely abstract debates about justice, goodness, and democracy) and the search for personal pleasure. And then there is a handful of people seeking to welcome the poor and the sick, who prefer going out to meet the other.

In one of your books, you advocate for the “cordial universalism of a we.” Talking about a “we” means talking about a history and ties of affection. What is the universalism of a we?

For a long time, I thought that the values of our society were based on a universally applicable foundation because they were inclusive: the liberal democratic “we” seemed like the thing that best embraced the cultural differences of others. Today, I see that this is a somewhat sugar-coated vision of our cultural identity that flows from a humanistic impulse that’s grown weak, in contrast with today’s dominant relativism and individualism. The only “universalism of a we” that I’m in favor of is that the “other,” whoever he or she may be, is always a good. Human beings are dependent; they depend on others to be themselves (to be born, to grow up in enjoyment or suffering, and to die). This the most universal concept in the world of human beings; it’s like the law of gravity for us. Consequently, any kind of nationalism is an enemy of humanity, and any accumulation of anger, jealousy, or hate is a step opposing humanity.

You help us to understand the root cause of the failure of the Enlightenment universalism we’re speaking about. When, for the most part, modern thought decided to leave “adolescence” behind and bring its reason into adulthood, it took a certain position on the question of the Bible. The facts contained in the Bible stories are now considered something that belong to an “age of the spirit” we have outgrown. To what degree would you say that this presupposition is still a forma mentis alive in all of us?

Spinoza was the first person in Christian Europe to radically question God’s revelation. He did so by dismantling the theological imagery of his time on the basis of historical-philological criticism: he placed the Bible in relation to the particular experience of the Hebrew people (and all that was connected to them–the prophets, customs, etc.). In other words, he relativized the outlook of the Bible. He titled his research Theological-Political Treatise because his

goal was to liberate man from superstition by combatting “the secrets of the monarchies and their interest in deceiving men, using religion to soften the fear they employ to enslave the people.” He said that only a republic could guarantee security for everyone, “Leaving each free to think what he wants and free to say what he thinks.” It was incredibly audacious. In Chapter 13 of that book, he maintains that “the Scriptures contain nothing but very simple teachings, merely requiring us to follow them. With regard to God, they teach nothing more than what men could imitate by living according to certain rules.” In the subsequent chapters, he lays out how faith leads to obedience, whereas philosophy teaches one to think; faith doesn’t require dogmas that are true, just obedience. What were the consequences of this? It led to “leaving adolescence,” or the separation between science and faith, which appeared in Europe for the first time upon the anthropological mistake of dividing man in two: the being who thinks and the one who acts. Loving the other has now become an imposition–a divine law which neither requires nor provides any kind of knowledge. This error tells us that, at this level of Christianity, ethics has been transformed into a mere collection of rules and obligations with no tie to reason.

For my part, I’d like to be able to tell you that in response to the question of the Bible there’s just faith. If you believe that Jesus was God-made-man in order to teach us things we’d forgotten about human violence as the instrument of dehumanization and reciprocal destruction, then you accept the entire text of the Gospels. Their universal value is love, embracing the needy, and putting an end to hate, jealousy, and anger. Or, in other words, that our life only has meaning when it happens side by side with the other. This is the universal.

Let’s go back to the separation between a faith that flows from historical facts and the universal nature of knowledge. Lessing reached the point of saying that “contingent truths of history can never be proof of the necessary truths of reason.” What are the consequences of a statement like this? Not only in reference to knowledge, which is always important, but for daily life…

Lessing was German; he was born 100 years after Spinoza and held his ideas in great esteem. A year before he died, he published The Education of the Human Race (1780), a text that paved the way for Kant’s rationalistic ethics. With the phrase you cited, Lessing defines historical truths as contingent and those of reason as necessary. And he says it’s impossible to pass from one to the other. He wrote it in the context of trying to demonstrate that Christ’s miracles occurred and that His prophecies were true in their own time, but that they’re no longer needed to fulfill the purpose they had at the time: that of “calling back the attention of the masses… so that men would follow in the footsteps” of those who performed miracles. Today, however, they are merely the “stories of miracles and prophecies in the past.” They are historical facts that do not, in themselves, contain any truth. Lessing denies the value of a witness; he denies that trusting other men and women is the foundation of truth. But you ask your neighbor to figure something out, don’t you? You trust that the other person is telling you the truth. Reading Aristotle or Euripides takes for granted that we trust that the person who transcribed those texts didn’t just make them up. This is not “news,” they’re a historical fact; it’s quite reasonable to believe them. The age of post-truth and fake news is a contemporary instance of Lessing’s rationalism: if everything in the past is only a story about the past, what sense would it make to believe one story over another? If truth is disappearing in this post-truth world, it’s because the relationship between me and the other has been eliminated.

In their teaching, the last few Popes have once again taken up the definition of Christianity as an event. What significance does that have?

Without having read them for over 50 years, I too have come to this conclusion about Christianity, having followed the path a number of Christians have been making for the last two years. They live and breathe Jesus and want to be like Him. “This is Christianity,” I said to myself. “Look and see that something significant is happening next to you.” When this is not the case, I think there’s no Christianity, just a set of superstitions, a combination of rites and doctrines, a mythical religion different from the one I left over 40 years ago. The significance of the fact that Christianity is an event is that a person can experience Christ as you would in a lab experiment. Because of this, other people can also observe the experiment and they may be enthralled by it. Or not, but that will depend on each person, not on the Christian. In any case, a person today would only become Christian through having encountered Christians.

I’m reading the book that you decided to write about Communion and Liberation in Spain. It’s fascinating because your perspective is really insightful. What has struck you most about this “tribe”?

The joy with which they live; the smiles of people who’ve come back to life.