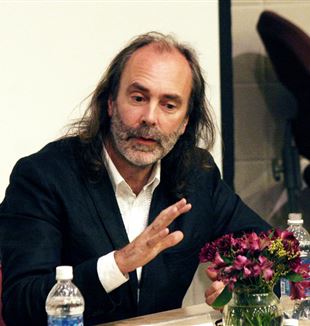

An Irishman’s Story: The Surprise of an Encounter

John Waters, editorialist of the "Irish Times," tells about himself, beginning with his experience at the Rimini Expo Center, the world of the mass media, the search for ultimate meaning, the life of the Church in Ireland, and the problem of education.You have said that your path away from the Catholic Church in search of freedom reflected a general trend in Irish society…

I grew up in society and therefore I’m part of it in some way. When I moved away from Catholicism in the mid ’70s, I wasn’t the first. Many of my generation did as well. But the same phenomenon wasn’t visible generally in the society for another 20 years. And then everybody said exactly the kinds of things that I was saying when I was 19: that the Church was hypocritical and outmoded, and that wherever God was to be found it wasn’t here, if He was to be found at all. What it means, I think, is that the public domain is perhaps 20 years behind the hearts of people. It’s the kind of thing that I don’t think we have understood yet in public realms, because the whole discussion of the nature of media is conducted by people with vested interests, who believe in the unequivocal virtue of the media and therefore are not open or willing to discuss the way in which it may have done the opposite of the greater truth-telling that it claims. The kind of mass media we have actually reduces the possibility for truth, so that the more there is, the less real communication there is. And so that would explain that time lag between personal response and what happened in the public square.

What is the view like now as you retrace your steps back toward the faith of your youth?

My journey is again connected to, sees, what is going on in the hearts of other people. But I know this not just by looking into my own heart. I know it through hearing people, not in the public square but in private, because now I’m alert to it in a way that I wasn’t on the way over. But still it’s forbidden in the public square and won’t be allowed for a long time. And that’s the project that I’m beginning to be engaged in: to find a language, to find a way to help to bring these ideas into the public square. They’re deeply contaminated ideas because of the history of the tradition, the hypocrisy, and the flaws in humanity in people, which of course shouldn’t come as a surprise. That’s the nature of the enterprise.

One of the obstacles on this road is the impermissibility, in the public square, of language about the ultimate meaning of life.

The extreme irony is that the kind of fanaticism imposed by Irish Catholicism in the past has now transferred to the enemies of Catholicism. It is like a metamorphosis culturally. The same energy of fanaticism which happened in the years of fundamentalist Catholicism is now driving a fundamentalist secularism against the Church. So, it’s a difficult time to try to articulate this, and you can easily be disqualified. It’s like a game of tag. As soon as you say something wrong, you’re out.

Historically, how did this metamorphosis come to be?

Up to very recently, Ireland was always a very poor country.

Catholicism as it was seemed to go well with that. It seemed to be a fatalistic kind of Catholicism, in the sense of, “We’re very unlucky people. We don’t win football matches. We’re never going to be rich.”

So Irish Catholicism was deeply flawed because it had all these separations in it: between body and spirit, mind and soul, faith and whatever, and between men and women. So we were easily persuaded that the material world was a more interesting and enjoyable place. And even though the bishops always say, “You can’t have God without the Catholic Church,” people say, “Well, let’s try it!” And then all these strange and psychic mechanisms which silence people and inhibit people and embarrass people and keep them from talking openly are all active. And these are very interesting phenomena because they’re not actually governed by any identifiable human intelligence. It is like an organism which is created out of the ideology and then operates to protect itself.

And there’s the whole sense then that what’s happening in the public square is about this prosperity, materialism, secularism; about going it alone, as it were, and there’s certainly no place in that for Catholicism. It’s unclear where God fits into this. The history of Catholicism was so joyless that there’s a sense of, “God wouldn’t really like this sort of stuff anyway, so we’re not going to embarrass Him by inviting Him along. You know, if you’re going to have a nudist party you’re not going to invite your great aunt Mildred!” So it’s not that we have anything against Him, but He doesn’t get out much now, so we’ll see how this goes.

And how has it gone?

All the time, people are knocked back off all the boundaries of materialism with the questions. Every time I speak, I find that there’s this sort of response, that people have the questions and they have the idea that “well, ok, we enjoy this world, we enjoy life, but we’re not satisfied. And we’re concerned for our children. What do we leave them?” Because what if this gets worse? At least we remember. I remember God. I was introduced to Him, I could fight Him, I fought Him, or His representatives on earth. But my daughter, our children, what do they have to fight? At the very worst, can we give them something to fight? So I think these are the things people are struggling with.

What is the connection between what you have read in Giussani and the hope that, in your talk here at the Meeting, you said you have found here?

I have the sense that he answers things in myself, that the kind of problems that I perceive, the separations that I grew up with in Catholicism really don’t have to exist, that we can be alive, enjoying ourselves, that God doesn’t have to be a synonym for “don’t.” And that reaches in, here at the [Meeting] conference: astronomy, music, poetry, art, skate boarding. It’s everything, life in all its totality is part of this. Well, that’s what I always wanted. So, I’m in a very early stage in terms of my journey thus far. But my next task is to read as much as I can of Giussani’s writings, and see.