Choosing to Live

A young person asks himself: “Should I go to college? What do I want to do and be?” 900 students preparing to finish high school met Fr. Carrón in Rome, asking for help in their choice. He challenged a more radical question: “What use is my ‘I’?”There’s a Battle in Course

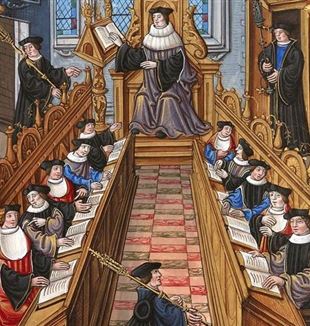

You cannot back out of this challenge–even not choosing is, in actual fact, a choice; life will not wait for us. “Good morning to you all. Are you awake?” asks Julián Carrón as he begins to speak. They are almost all awake. It’s early on Sunday morning in the Aula Magna of Rome’s Urban University (which is not big enough, so there are two other rooms connected by video-link), but it is cozy enough to be able to see each others’ faces on the steps situated above one of the finest views in Rome. Almost all of them are awake, these high school students who arrived in the early morning, hours before the Regina Coeli in St. Peter’s Square with the Pope, after long, uncomfortable journeys. They have all switched off their cell phones and taken out pen and paper to take notes, as they listen to someone who has already made a part of the journey and wants to help them along.

It is not easy to find your direction, to recognize the criteria with which to choose a faculty or a job, to decide what form your adult life will concretely take.

“We will study law,” think Maddalena and Elisabetta. Emanuele, who studies at the same classical high school in Milan, has already opted not to follow his passion for music. Such choices are probably the fruit of reflection, but these prospects are destined to be overturned in the course of the day. “I admit that I haven’t understood much,” says Elisabetta. “But after the meeting, I am reconsidering everything, because it introduced criteria different from mine, criteria that concern not only the university, but the whole of life; a measure different from that of the world, that takes into account all I am and all I desire. I have learned to aim higher.”

Don’t Stop

The most concrete way of helping these young people not to let themselves be crushed by their own and others’ expectations is to remind them of “the majesty of life,” to use a term dear to Giovanni Testori, of the greatness of what is at stake, not only before entering a university but in every moment of existence. So the opening song chosen by Carrón and Franco Nembrini, responsible of GS, was Claudio Chieffo’s Parsifal (Percival–the knight on a quest for the Holy Grail). “Don’t stop, Percival, and let there be always the unique voice of the Ideal to show you the way.”

“Don’t stop.” It’s not as easy as it sounds; no one dreams of getting bogged down in life “at the court of the midget souls, who repeat the gestures they cannot understand,” but the battle is as invisible as it is crucial; the temptation is to take the easy way, to let yourself be conformed to the worldly mentality, or to just follow uncritically the advice of many wise counselors, often sincerely convinced that they want the best for their students, but not able to perceive the vast breadth of totality. In time, all this, in an almost imperceptible way, makes life wither, blocks the growth of the personality, numbs the humanity in a world of easy surrogates and dwarfish joys, until something (a song, a face, the reaction to a great sorrow or a great love) reminds the heart of its primordial greatness. The ideal invites us to fight against this reduction that is always waiting to trap us. The drama in this period of life is that life itself forces you to choose. But the first thing is not even what to choose. What comes first is the question, “Why is life worth living?” “A man walks when he knows where to go,” wrote Chieffo. Fr. Giussani teaches us, “Man finds energy for action only in clarity and certainty.” And Fr. Giussani asked himself, “Why do I exist? What use is my ‘I’?” “The first decision is to take this question seriously,” Carrón comments. To block it means to destroy man’s nature, to block the drive for life. “Imagine a part of something, the wheel of a car, for example, asking itself: ‘What use am I? What am I doing here?’ It can be understood only in terms of its relationship, its link with the whole.” What am I called to do? To discover the way in which I can be useful to the world is my road to happiness, to my fulfillment; I don’t lose myself, but win myself. Self-realization is serving the world, although the mentality we are immersed in suggests the opposite. “It is fundamental to understand this, because many people think that the only way to realize oneself is to affirm oneself, and so they end up alone in a hiding place, asking what meaning life has,” Carrón continues. The hiding place can even be a “place in the sun,” a place of comfort and success. It’s the usual, old trap, the dream of becoming more equal than others through a made-to-measure short-cut, whether it be an esoteric rite for initiates or a bank account with a lot of zeros.

“Percival, you have to fight, you have to look for the Fixed Point among the waves of the sea and that island is there…”

Percival must fight to remember the greatness of his life and follow the Sign, which comes from the people he meets, a Sign which, written with a capital S, is synonymous with vocation. This expresses itself in a radical question: “How can I,” with all that I am, “best serve the kingdom of God?”

In response, Carrón re-proposes the three criteria indicated by Fr. Giussani. First to consider are one’s natural inclinations and gifts, that is, “abilities, desires, drives, temperament. These are precious gifts that we must set at the service of something else,” but without censuring them, because the greatest mistake you can make is “diffidence toward your own inclinations, toward what is right, what is pleasing in so far as it is authentic, innate.” The Mystery calls us by means of this, inside the flesh. “He shapes us within our guts in order to tell us what He is calling us to, because He is the one who made us like this.” So, the second criterion consists in the “inevitable circumstances”–the “more friendly” factor, because it shows you more clearly the road to follow, without getting bogged down in complaints, or in particular expectations–like wanting to take part in the Olympics after you have been crippled in an accident–or shut up in the dream of reaching an objective, but looking attentively with curiosity at “how the Lord will manage to bring me to happiness through my being crippled.” The third factor is social need, “the need of the world and of the Christian community.”

It is using all this that we can come to grips with “the two basic matters we have to decide”–vocation as a state of life and the choice of profession, taking account of a fact: “Our vocation cannot be a ‘creation’ of ours.” An Other decides it. It is rather a recognition, an acknowledgment. “We must acknowledge something we have been destined for.” We are free either to accept or not, either to educate ourselves in constant attention to the signs of reality or to let ourselves go, in a kind of group anesthesia of things to do, like everyone else. The modern conception of life is very far away from this–all the “great” desires, all that has the breadth of totality is seen as an exaggeration, fanaticism, or dangerous extremism.

A Companion on the Journey

“What we have heard is like a breath of fresh air,” Maddalena says. “You get to thinking that you really can become a doctor because there is no need for lawyers, but because you look truly at what matters for you in life.” “I began to think again about going for music,” said Emanuele. “I had decided that, after all, it wasn’t so important, but instead it was as if Carrón were telling me, ‘For me, that passion of yours is important.’” “We were there in front of someone who was more concerned about us than we were ourselves,” commented Maddalena. Fr. Carrón had promised this in his message at the GS Triduum in Holy Week: “I am your companion on this journey.” This is an embrace of someone, says Maddalena, “who clearly loves you.” This is what 900 kids had in their eyes and hearts that morning, the same kids who shortly afterward swarmed toward St. Peter’s Square for the meeting with the Pope, and toward a greater life.