Disarming Beauty Review

"Christianity ... is the encounter with the person of Jesus, the mystery who entered into history to become a companion to human beings and respond to their structural need for happiness." Disarming Beauty is reviewed on Reading Religion.The following review first appeared in Reading Religion on October 3, 2017.

Julián Carrón’s Disarming Beauty inserts itself in the ever growing literature of reflections about the role of Christianity in contemporary society. Julián Carrón’s contribution to the debate is a welcome addition, for it represents a unique perspective that defies the usual ideological camps that characterize much of the current conversation. Carrón is a Catholic priest and theologian who is the president of the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation, an ecclesial movement within the Catholic church born in Milan in 1954 from the life and thought of Monsignor Luigi Giussani that has now spread all around the world. While it is not widely known in the United States, Communion and Liberation has had a pivotal role in shaping Catholicism from the 1950s onwards, and thus this book is a precious resource that opens a window upon the theology, life, and method of this important ecclesial movement.

Carrón shares with many contemporary scholars the perception that we live in a moment of crisis. While it is undeniable that there are problems with our schools, in our families, in our political and social life, and in our economic system, according to Carrón all these malaises are symptoms of a deeper problem, namely, a crisis that touches the very foundations of our society. Nothing is self-evident anymore, Carrón argues, and the great values at the root of Western culture—reason, freedom, equality, justice, the dignity of the person, and so on—have lost their clarity. This, explains Carrón, has created a human crisis where what is at stake is the very meaning of what it means to be a human being, a situation that has left many either paralyzed by fear of the future or mindlessly bored by the present.

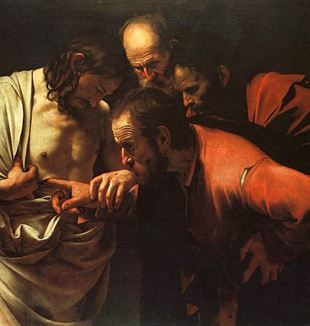

Considering the nature of the challenge, Carrón deems many of the attempts of today’s Christians to respond to the current crisis as destined to fail. Neither anger against a cultural tide that is not going in the wanted direction, nor retreat into safe spaces, nor the reactionary attempt to fight for traditional values will suffice. Instead, rather than being something to be lamented, the crisis is an opportunity for Christians to rediscover and communicate Christianity in its original elements. Christianity is more than the transmission of a set of rules or of a body of theological notions. Christianity, according to Carrón, is the encounter with the person of Jesus, the mystery who entered into history to become a companion to human beings and respond to their structural need for happiness. It is an event, “a fact that did not exist before and, at a precise moment, was introduced into history. Everything else is a consequence of that” (64). As it was a human encounter that changed the lives of those who first met Jesus, so now it is through a human reality that Christ remains present in history. “Christ remains present in his Church,” explains Carrón, “making possible the contemporaneity that allows people of every age to come into direct relationship with him” (66). Despite all the difficulties that our culture poses against it, the Christian faith has a chance in today’s world because people can verify here and now its ability to correspond to the longing for fulfillment that everyone nourishes.

Amidst the pluralistic culture in which they live, Carrón says Christians are called to find “a way of being present without a will to dominate or oppress, and at the same time with a commitment to living the faith in reality, in order to show the human benefit of belonging to Christ” (55). It is necessary for fundamental human values to be alive in someone, Carrón says, for them to be able to evoke interest and to rescue people from today’s confusion, which is why the greatest contribution that Christians can give to their contemporaries is to be witnesses of the fullness of life that comes from having being seized by Christ. What we need, argues Carrón, is a society that offers a space of freedom where different proposals of meaning can be in dialogue, so that truth seekers might encounter one another and together rediscover the meaning of their existence. Christians are not afraid of such freedom, he insists, for the truth of the Christian announcement is not something that has to be imposed with force, but a discovery that reveals itself to be credible by the newness and beauty that it generates in the life of those who take it seriously.

While this book suffers from some of the problems that are common to all collections of essays—some arguments are not systematically developed and leave the reader wanting for more explanation—and certain passages might lack some clarity for those who are not familiar with the European context, Disarming Beauty contains an engaging and original proposal. Carrón does not limit himself to a diagnosis of the contemporary crisis and to a description of what it means to be Christian. Instead, in the second half of the book, he also tackles the fascinating challenge of what it means to educate today, and he then sheds light upon some the most pressing issues of our age, including family life, terrorism, and the fractured state of our political life. I highly recommend this book to all readers who are interested in thinking along with the author about the difficulties that we face and about what we can do to respond to them.#DisarmingBeauty