The Christian Encounter

"Carrón points out that many of the truths we have held for some time to be self-evident became obvious only after the advent of Christianity; with its current decline, so too goes the obviousness." Disarming Beauty is reviewed by National Review.The following article first appeared in National Review on October 2, 2017.

"Do we Christians still believe in the capacity of the faith we have received to attract those we encounter . . . [with] its disarming beauty?” That’s the question or challenge that Julián Carrón, head of Communion and Liberation, a lay ecclesial movement centered in Italy, puts before his reader in Disarming Beauty. The book relies heavily on the writings of Luigi Giussani, the founder of Communion and Liberation.

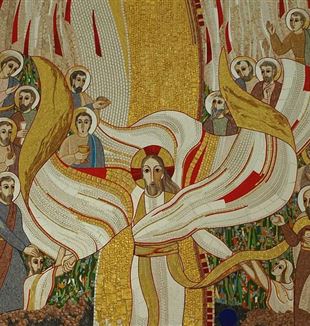

The essays here were originally published separately but have been reworked with the aim of creating a coherent presentation. The volume is at times diffuse and at times repetitive, yet its manner of framing the contemporary situation of belief and theology is arresting and largely persuasive. Its core teaching is that of Giussani, whose life and thought Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, speaking at Giussani’s funeral, encapsulated thus: “He understood that Christianity is not an intellectual system, a packet of dogmas, a moralism; Christianity is rather an encounter, a love story; it is an event.”

Carrón presents the key insight with greater theological precision and depth: The “contemporaneity of Christ’s presence” means that each believer has access to a personal encounter with Christ, as powerful as the encounter the disciples had with Jesus when he lived and taught among them. This has implications for how we understand tradition and evangelization. The transmission of the faith from the past into the present involves more than the handing on of doctrine. It involves primordially a repetition of the original experience, in which the beauty of God seizes the soul, draws it to him, and utterly transforms it. As Paul says, “Whoever is in Christ is a new creation.”

Carrón thinks that invitations to this “encounter” should be at the forefront of the Church’s engagement with the contemporary world. This is the essence of evangelization. Writing as an orthodox Catholic, Carrón underscores the deep continuity between Pope Francis and his immediate predecessors, John Paul II and Benedict XVI. He also defends Francis’s approach of putting the encounter with Christ at the center; such a framing of the Gospel, Carrón believes, is the best response to an era of “epochal change.” In a period of rapid cultural upheaval, believers typically find themselves adopting a defensive posture. This is exhausting and self-defeating, and rests upon a failure to understand the peculiar features of our time.

Carrón focuses, correctly in my view, on the vanishing of any consensus about what is obvious or non-negotiable: Our age witnesses the “collapse of the self-evident.” As much as they disagree on which propositions are obviously true, both Right and Left continue to argue and act as if self-evidence held. In the absence of assertions winning assent, both groups resort to ad hominem attacks, impugning the intelligence and morality of those who fail to see what the other group deems obvious. The shrill and acrimonious character of our public debate betrays a deep insecurity about whether there is any clear foundation to the positions being advocated, and about the continuing viability of persuasion through public discourse that is essential to a healthy democracy.

If Carrón worries that the so-called Religious Right is too eager to assert arguments and rules, he also accuses the Left of dishonesty in affirming universal values, dignity, rights, and equality while it severs the links of these values to their historical roots. One might note that the deeper problem here is not so much the abandoning of history but the nonchalance about the absence of any conceptual basis for much of what passes on the left for self-evident principles. Carrón points out that many of the truths we have held for some time to be self-evident became obvious only after the advent of Christianity; with its current decline, so too goes the obviousness.

Carrón could have said more here about the differences between Christianity and modernity. While it is certainly correct that many modern motifs grow out of the culture of Christianity, only in modernity is there a promise, indeed a boast, that humanity is rapidly approaching enlightenment — a period in which clear and evident principles of freedom will be universally affirmed. The current deterioration of self-evident shared principles is, therefore, a failure principally of enlightened, secular modernity, not of Christianity.

An objection that some might raise concerning Carrón’s account is that the insistence on the primacy of the encounter and on the futility of argument might seem to entail relativism or historicism. But that objection is wide of the mark: Carrón is most emphatically not advocating a soft relativism. He insists that certain fundamental questions endure and are unavoidable; the longing for the infinite is unquenchable. More dramatically, he insists that “knowledge of faith becomes knowledge of reality” and that faith submits itself to the tribunal of human experience. The encounter that originates faith is an experience of what one can touch, see, and recognize. The chief task of faith in our time is to reawaken the religious sense, which is not a matter of a retreat into some private, idiosyncratic way of seeing the world. The religious sense teaches us to see reality anew and as it is.

What we are experiencing is a crisis of the human as such. Carrón cites a revealing passage from Philip Roth’s novel The Counterlife: “All I can tell you with certainty is that I, for one, have no self. . . . What I have instead is a variety of impersonations. . . . I am a theater and nothing more.” This is the diminished, evanescent self that lingers in the wake of consumerism: the self of market preferences and progressivism, the self that has cast off any and all encumbrances to self-validating choice. It is important to see that for Carrón, religion, understood generically, is not necessarily a corrective to this situation. He quotes the late Catholic thinker Ernest Fortin: “The death of God is perfectly consistent with a burgeoning religiosity.” In our time, religion itself is often a “product to be consumed, a form of entertainment, . . . an emotional service station.”

The encounter with the disarming beauty of God resists translation into utilitarian projects — of self-help or progressive social reform. Another danger Carrón fears is legalism. He repeatedly insists that the Christian encounter is not moralism; it is not a law. And that, as the earlier quotation from Ratzinger indicates, is certainly correct. The primacy is the relationship with the person of Christ; apart from that relationship, the Gospel is “not a manual for living.”

But here again Carrón’s account, cogent as it is, would profit from greater differentiation. The Jewish and the Christian conceptions of law are quite different from narrow, modern conceptions of morality and law, which tend to be abstract, impersonal, and procedural. Instead, on the Christian view, articulated brilliantly for our time in the work of the Belgian Dominican Servais Pinckaers (see his book The Sources of Christian Ethics), law is intimately connected with virtue and with traits of character, and all three of these are incorporated into a vision of human beatitude.

In other words, the encounter with divine beauty not only disarms; it also calls to unyielding allegiance. It is a purification of the heart that enables us to will one thing. What Ratzinger calls the “love story” — and Carrón the “encounter” — is a call simultaneously to freedom and obedience, happiness and suffering, rejoicing and mourning.

#DisarmingBeauty