"Adhere to Christ, build the church"

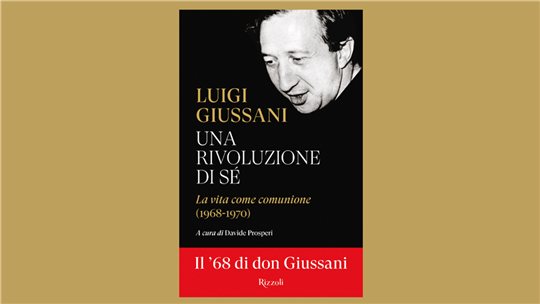

An excerpt from Davide Prosperi's Preface to the new book of Fr. Giussani, "Una rivoluzione di sé. La vita come comunione (1968-1970)" [A Revolution of Self. Life as Communion (1968-1970)].It is with a certain emotion and a renewed gratitude that I prepare myself to present the texts collected in this volume. They belong to a delicate and crucial moment in the history of Communion and Liberation (CL). The texts refer to the years 1968–1970, a period in which the experience born from Father Giussani in 1954 undergoes, as a result of the explosion of ’68 in Italy, a great shock: a thousand high school kids, half of the adherents of Gioventù Studentesca (GS), and a few hundred of the university students that had come from their ranks, distance themselves from the Movement. It is certainly a moment of trial, which unexpectedly will also reveal itself as an important step toward the rebirth of the Movement. Beginning in Fall 1965, having left the guidance of Gioventù Studentesca, Giussani joins in the gatherings of the Charles Péguy Cultural Center, founded in 1964 and promoted by those who, having finished their university course, desired to live in continuity with the experience begun in the previous years.

After the first year, in which it is concerned mainly with cultural activities, the Péguy Center becomes more and more clearly a place for deepening the faith according to the accent proposed by GS, representing in fact the continuation of the “movement” that appeared at the Berchet High School in 1954 and the beginning of that reality that a little later would definitively assume the name of “Communion and Liberation.” In fact, as the time of the cocoon marks the passage between the potential energy of the caterpillar–which already has everything in itself hidden in embryonic form–and the full expression of the butterfly, the Giussanian experience of the Péguy Center represents the bridge of transition from the adventure initially born with GS among the school desks to a renewed awareness of the universal horizon that desires to embrace every aspect of human existence at the adult level, as it will find full realization in CL. Those years from 1965 to 1968 are, in a certain sense, years of experimentation in search of a structure, in circumstances that remain difficult, but are not at all lacking in fruit. In September 1968, on the occasion of the Beginning Day (whose content can be found in the first text published here), taking account of the steps completed, Giussani makes this point and launches out again, defining the nature of the Péguy Center and tracing its guiding lines.

And so we arrive at this volume. It contains the transcriptions of the lessons given by Father Giussani from 1968 to 1970 in the two main events which mark the path of each social year: the Beginning Day and the Spiritual Exercises, the one and the other spaced not too far apart, in an arc that goes from September to December. Reading these pages we are catapulted into an enthusiastic richness of “discourse” (to use the expression dear to the author) that is, of a proposal whose radicality and clarity are not only revealed as decisive in re-launching the experience of those years, but also constitute a powerful and illuminating call for our present (a contribution to that discover of the potentiality of the charism wished by Pope Francis in the audience of 15 October 2022¹).

Christian life as communion

Already in the first text, Beginning Day 1968, Father Giussani concentrates on “re-specifying and re-launching” (see here, p. 5) the common aims, principles and directives to which to pay “respect” (p. 8): the subjects, in short, that should delineate the physiognomy of the Péguy Center and motivate our belonging to it. Giussani indicates three such subjects and defines the first two “pillars” (p. 12) or “cardinal points, essentially such” (p. 13), of the conception that “qualifies us” (p. 12) and that “specifies our vocation in the house of God” (p. 11). It is only living this vocation, he adds, that “we can become useful to Holy Mother Church” (p. 15).

The first point, on which I will return in a minute, is “Christian life as communion.” The second: the underlining of the fact that “collaborating with the world passes through lived communion” (p. 13), and the third is an “application” of the first two: the friendship of the Péguy Center, that is, “must be conceived and thus organized […] according to those two principles,” every other consideration would suffer from a “partial setting” (p. 16). Therefore, Giussani underlines, “the environment marked by our friendship is, on the one hand, substantially, in essence, a will, a desire, an attempt, an effort, an experience of communion, of engagement with lives and, on the other hand, through this, a development of our collaboration, of the collaboration that we have to give to the world” (p. 14).

Of the three points, the one that gets developed the most is the first. “‘Communion’ means involvement of my life in yours and of your life in mine” (p. 12). An involvement “in the name of Christ” (p. 14), whose only motive is the Christian event and whose ultimate origin is the power of the mystery of Christ. Communion is “founded on the fact that God has chosen the other just as he chose you” and has allowed you “to find him along your way with the same vocation, which means with the same Christian accent, with the same Christian will” (p. 30).

This first pillar expresses a key insistence that Giussani has had since the beginning and that has to do with the event of the Incarnation, its contemporaneity. This “communion” has in fact in the “Mystical Body of Christ”² its “total perimeter and always more mysterious expansion in history” (p. 12). The radical assumption of the Pauline definition of the continued reality of Christ in history as “Mystical Body” is certainly constitutive of the Giussanian conception. God did not come into the world in a marginal way, as an isolated point in time and space, and therefore unattainable for those who would come after. Christ came into the world in order to remain, and the Church is His tangible and mysterious prolongation.

But, Giussani underlines, “the mystery of Christ would be an abstract wind, if it did not become concrete in the environment of daily relationships that you live. Therefore, the word ‘communion,’ dialectically, falls between the pole of the ultimate perimeter of the Mystery and the ephemeral contingency, the ephemeral present” (p. 13). That ultimate perimeter, the mystery of communion, would remain abstract, far away, if it were not perceived and lived in the relationship “elbow to elbow” with concrete people, in the involvement of your life in mine and my life in yours, if, that is, it did not emerge where I live, in “our communion,” which, of course, “is not the source of the value, but is the moment in which that source of value that is the mystery of the Church emerges” (p. 17).

We must look on these observations in the context of that experience of the Church–with its moralistic, individualistic and intellectualistic accents–with which Giussani dealt in those years in order to grasp fully its explosive force. Despite the extraordinary event of the Second Vatican Council, the Church struggled to offer experiences that responded adequately to the signs of the times. GS, which represented a contribution in this direction, had found enthusiastic openings but also many resistances along its path. On the worldly front, so to say, we have naturally to keep in mind the cataclysm of ’68, of which Giussani already had a clear awareness and which gave depth to so many of the positions that he takes in the pages found in this text.

But the explosive force of the Giussanian proposal reveals itself intact in our current situation, in front of its limits and its needs, of the distress and the solitude that wound it, with new and maybe more insidious forms of individualism, determined by the pervasive action of technology and by the deep laceration of the social fabric, with the consequent lack of places that generate humanity. Only a Christianity faithful to its nature can in fact constitute a concrete point of redemption and hope for a humanity that is so worn out, in a troubled and fluctuating search for a path. And it is precisely in “Christian life as communion” that we experience the pertinence of the Christian announcement to the hunger and thirst for meaning and for destiny of men and women, but I would like to say above all of the young people of our time. This is the ground on which Christ’s promise can be verified: “Whoever follows me will have eternal life and the hundred-fold here below.”³ A great word, “hundred-fold,” to which Father Giussani gives again all the depth of a living experience in the communitarian proposal of the friends of the Péguy Center. In Christian life as communion we can have the experience of a real, present Christ, according to what He has established (“Where two or three are gathered…”⁴) and of a faith that invests life and changes it. It is this lived communion that makes us discover the benefit of faith and nourishes that faith in us. For this reason, Giussani insists on the fact that this communion, this involvement with lives, “is not a private thing between us or just a particular choice, but is the Christian life” (p. 14), simply and essentially. Wherever it is ignored or sociologically reduced, minimized, or misunderstood, it is Christianity itself that is emptied. “Communion” belongs in fact to its ontology, as Giussani will reaffirm many times in the following years.

[…]

¹ “The potential of your charism is still largely to be discovered, it is still largely to be discovered” (Francis, Address to the members of Communion and Liberation, 15 October 2022).

² Cf. Romans 12:5; 1 Corinthians 6:15; 12:12-27; Ephesians 4:16; 5:30.

³ Cf. Matthew 19:29; Mark 10:29-30.

⁴ Matthew 18:20.