The machine of the world

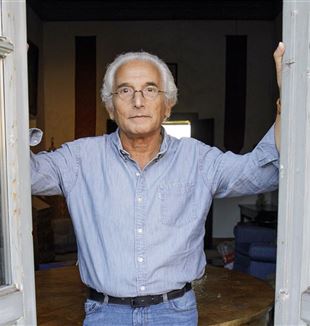

Technological developments that revolutionize everyday reality: What becomes of the human after having delegated many functions to the computer? In February Traces, Miguel Benasayag, psychoanalyst and neurophysiologist, provides answers.Miguel Benasayag, Argentinian by birth and French by adoption, is a psychoanalyst and neurophysiologist. He works specifically on problems in childhood and adolescence, and has been studying the changes brought about by the digital revolution and their impact on the human for years. There is a high risk that, with the development of artificial intelligence, the human being will be reduced to a sum of functions, he says. But “the life of man is to exist, not to function as a machine.” What remains of the person after delegating certain functions to machines? “Everything remains.” Because the human is “irreducible to the elements and processes” of which they are made. And what about transhumanism, which fantasizes about a person without limits? “Delusional theories.”

The impact of artificial intelligence has been compared to that of the industrial revolution. Two hundred years ago, production automation took manual tasks away from the person, and now AI is taking away some of their intellectual activity: it writes, analyzes, decides for them. What then is the person? Is there not a risk of defining them “by subtraction” as the remnant of what remains after being placed in the hands of machines?

That is the temptation. But we must say who the person is positively, not after the machine has stripped them of certain functions. Today, the human being is defined as a sum of modules, of parts. This is a weak point of view, originating from a “modular” philosophical conception that does not consider the fundamental difference between an aggregate and an organism. An aggregate is a sum of functions; the organism, on the other hand, is a unitary entity and is not defined simply by the way it functions. In biology, in epistemology, we look at Kant’s definition in the third Critique, where he says that an organism functions “for” and “through” all of its parts, which are not conceivable on their own. Each part of an organism functions according to a dual principle: according to its own nature, but also according to the nature of the whole organism. For me, this is the central problem of our age: the confusion between what is organic and what is aggregate. Machines can do a lot of things; they can fascinate or frighten. But the basic problem is to understand the difference between organism and artefact and the particular singularity of the living.

The oneness of the person, their true “I.”

The person is a unitary being, irreducible to the elements and processes of which they are composed. An organism participates in life insofar as it has relationships and belongs to a long-lasting species. I work with the concept of a “biological field”; i.e., a permanent interaction between living beings.

Do you think the word “intelligence” is appropriate for what we now call “artificial intelligence”?

Not really. The machine is not intelligent in itself: it can predict, calculate, do a lot of operations, but intelligence for the living–not only for the human being–is always a matter of integration between the brain and reality, not just the ability to make good calculations. The rationality of artificial intelligence is very poor. For example, it cannot accept the inherent negativity of life, or the fact that bodies desire, are subject to drives, and do not always act positively. Even thirty years ago when I began this research, I wrote that we were talking too much about “intelligence” related to machines, and that this would have negative consequences.

What would you call artificial intelligence?

An interesting artefact. Machines. Conversely, by constantly talking about intelligence and artificial life, today we have an artificial conception of biological life. The discourse has been turned upside down. In my field of research, the majority says that there is a natural consensus between intelligence and artificial life, and biological and cultural life, while the difference is only quantitative. I say the opposite; i.e., that there is a qualitative difference but that this is very difficult to affirm scientifically because we reason only in terms of measurability. People like me are considered idealists, “vitalists,” who want to include a non-scientific element in the definition of life.

In your research you have always praised the limit. The person can make mistakes and has a sense of their limit, but the machine does not.

That is how it is. For me, limit does not have a negative meaning: it is what defines my way of being in the world. We are limited because we have points of view, affections, responsibilities. On the contrary, it is antiscientific to program a machine with limits: the machine must not have any because it must always function perfectly. Instead, the human being, and more generally the living being, is defined by its limit, which is not a boundary that prevents it from living, but, rather, the condition of life.

A life without limit is the myth of the contemporary world.

It seems unbelievable, but all these delusional transhumanist theories, which speak of a life without limits, really do have a huge audience. The idea that limits are arbitrary, that human beings have no reason to accept them, is absolute madness.

How do you explain the success of these theories?

Everyday life is steeped in them. The removal of limits is the basis, for example, of neoliberalism, which wants to deregulate and deterritorialize everything.

Deterritorialize?

For example, I like to eat my country’s seasonal fruits. But there are those who want those fruits all year round and are willing to have them flown in from abroad, or use huge amounts of water to grow them in unsuitable but closer locations. However, if I say that this makes little sense, that life is made of cycles, rhythms, and even rituals, I have no place in postmodernity. I am considered an obscurantist because I want to set limits. Deterritorialization starts with the idea that the human being must not accept any limits. That is suicidal.

Does the person today also reject limits because they no longer recognize that they were created?

The human being considers itself as having been made like a machine. This is a plastic creationism. Why suffer the limit of organicity? Thirty years ago, this question was only asked by psychotics and psychiatric services: Why must I accept limits, why must I accept death? There is a very funny play by Eugène Ionesco, Exit the King, in which the sick protagonist does not admit that he must die. Ionesco wanted to mock Western individualism, but today the common feeling is this: limits are arbitrary boundaries. And we have an enormous, fantastic power in our hands, but for the moment itcauses changes that we cannot master because we do not know how to tame it.

What do you mean by that?

You compared machines to the Industrial Revolution. I rather compare them to the discovery of agriculture in the Neolithic period: intensive cultivation initially caused the death of a third of humanity at the time thanks to deregulation, deforestation, plague, and tuberculosis. We are in a similar situation: a powerful revolution of which we do not have full control. For anthropologists, we are even on the eve of a new great extinction. And the poor, little human being finds itself truly frightened.

Should the machines be stopped?

Impossible. One cannot look at the future through a rear-view mirror. In reality, we are already hybridized, even if we do not realize it. It is a hybridization that is not anatomical but physiological, related to functioning. For example, I worked for years to understand the influence of digital devices on the brain. It was very easy to see how the brain structure of those who delegate certain brain functions to GPS has changed, both physiologically and anatomically.

If some faculties are lost, are others improved?

Not possible. This is how the central nervous system works: it delegates certain functions and recycles the freed brain region. We saw this when writing was invented and the part of the brain that had until then been dedicated to mnemonic activity was then used for reading and writing. These are very slow processes, taking even hundreds of years. And today, with the speed of machines, neurophysiology shows that the delegation of functions causes an atrophy of the freed brain region. In the case of satellite navigators, there are subcortical nodes that deal with time and space and therefore with cartography: the nodes that delegate the function to the GPS do not have time to recycle themselves for another function and atrophy, at least for the time being.

Does this mean that artificial intelligence can cause natural obtuseness?

A weakening, sure. We also see it in children who spend a lot of time with video games or in front of a screen. I do not say this in a technophobic manner, because I am nota technophobe, but simply because we are not aware of it. It is not for nothing that Silicon Valley geniuses send their children to schools without computers and make them study Latin and Greek. Neurophysiology says that before the age of three we should not put children in front of screens. But families are not aware of this, especially those who have no access to culture or lack discipline.

So are machines our enemy?

No. But we need to know them and reestablish an otherness. The machine is the machine, living is living; living should not be defined as what remains after having delegated certain functions to machines. Losing this distinction is very dangerous because it puts the person and the artefact on the same level. But the person’s life is to exist, not to function as a machine. What remains of the person after having delegated certain functions to machines? Everything remains. We simply have to learn to exist, cohabiting with this new power, which, since we do not have full control of it, can be dangerous.

What then is our task?

The problem has two aspects. The fundamental thing is to understand that we must be able to identify what we are, what our singularity is, and that we cannot define it as residual. We must return to an otherness: the difference between man and machine is radical. The second step is to regain the ground we have left to the machine. I often recall how the invention of the elevator did not take away the possibility of and taste for walking. It is best to abandon the somewhat stupid idea of happiness as motionless comfort, doing nothing, being served by the new slaves; i.e., the machines. We must rediscover a desire for happiness that is different than this idle vision, which very much reflects the American way of life.

Read also - Artificial Intelligence and the sleeping soul

The flip side of the coin is that today we are often measured by performance. The machine runs and the human must keep up.

The current aesthetic is to become an increasingly high-performance machine. So, happiness would be on the one hand doing nothing while the machine does everything, and on the other, functioning as a machine while also shedding the anxieties associated with existing and the search for meaning. We must all actively resist, not against the machine, but against stupidity.

In his message for the World Day of Peace, Pope Francis says that artificial intelligence can magnify inequalities. Do you agree?

The machine produces a world of cold calculations, which do not provide for sharing, in which the strongest remain the strongest and others are excluded. Statistics considers the averages, the masses, and cuts out those on the margins. But the number of these minorities in the world continues to increase. I believe that the pope wants to warn against the paradox whereby machines are believed to be at the service of everyone while in reality they work for those who govern them.