Meeting 2019: Your name was born from what you gazed upon

The talk on the title of this year’s Meeting by Guadalupe Arbona Abascal, Professor of Comparative Literature and coordinator of the Master in Creative Writing at the Complutense University of Madrid.Today I am overwhelmed by three feelings.

1. I am very grateful for your invitation.

2. At the same time, I am very embarrassed. I have been coming to the Meeting for years and I have always been sitting where you are. Or I looked for a screen in order to listen to your voices and learn. I will do what has been asked of me and, on the other hand, I will do what I know how to do, which is to recount some nice stories that speak of our truest desires.

3. Thirdly, I am disappointed that I do not speak your language well and that I will have to get by with my mix of Italian and Spanish. Even so, I will say to you in the words of the Spaniards that lived in the age of Cervantes: “Italy my fortune”. I feel it like this.

Thank you to everyone and to each and every one of you who has contributed to the enlargement of my soul.

The phrase quoted in the title of the Meeting is very suggestive and offers many points of interest to us all. Firstly, I will consider the two initial terms. The name and birth. All of us received a name when we were born. We know well that a new-born is given a name so that he passes from being nobody to being someone, to being himself, with his name, unique and unrepeatable. In almost all cultures it is the parents who, knowing that a new being will come into the world, come up with a name for their child. They have called us by our name since we were little, even when we still could not speak they told us: Clara, Martina, Fernando. When we began to walk they would call us- Ana, Sergio, Cecilia, Javier- to warn us of any danger. And when we grew they still woke us up in the morning to go to school and to begin the day: “Come on Guadalupe, get up, you have to go to school”.

“Your name was born from what you gazed upon”. Wojtyla refers to Veronica, the woman who, drying the face of Christ with a linen cloth whilst He climbed to Calvary, conserved the image of the dirty face, stained with blood and sweat.

That is why this phrase, referring to Veronica, raises in us the question: if we already received our name at birth, if it is a good that has been given to us which was confirmed as we grew and discovered things, why should it be born from what we look at or, moreover, from what we look at intensely? What is curious is that for Veronica the name was generated not at birth but from an encounter. Perhaps, therefore, another name is necessary, a name that indicated the need to be reborn and renamed? We do not know what Veronica was called- according to certain traditions she was the woman who suffered from haemorrhaging and who touched Christ’s cloak in order to be healed- but she certainly had a name. The Gospel story tell us that she was marked by the One she had cared for; sympathetic to His pain, she became one with the Man she took pity on. And so Veronica acquired a name and was reborn. Her story was the story of a second birth.

The phrase is of great pertinence to our age, because I believe that there is no time like ours in which the nostalgia of birth itself has been felt so much and with such intensity. Some literary works, that I have read and re-read because they spoke of me, of my human experience, come to my aid. My talk will develop around four points, each one related to an image by Guillermo Alfaro.

1. “I haven’t been born yet”

The men and women of our time express their desire for birth with an inner cry, a longing that rises from the deepest root of life. Sometimes, it manifests itself as a slight nostalgia or a fleeting feeling that creeps into the heart: the whisper of something that you have lost while living and to which you would like to return. Other times, it can manifest itself as an exasperated need or a painful groan. In both cases, it arises from a feeling of melancholy towards a world which, at the time it was discovered, was perceived as ordered and harmonious, spotless, provident, happy.

Film director Pedro Almodóvar reveals the nostalgia for his childhood in his most recent film. The protagonist of Dolor y Gloria [Pain and Glory, 2019], which is the name of the film, is a worn out film director. After years of fame and success, he feels empty and depressed. His life passes in a deep apathy, nothing interests him anymore. He has stopped writing, he no longer directs films, he does not leave the house, he does not respond to invitations. He lives in a perennial and tormented insomnia. He only managed to recover a sliver of life if he remembers his childhood, scenes from when he was a child and lived in a very poor Spanish village on the 1950s. This period of living sheltered in a cave or having to survive with very little did not prevent him from feeling the love of his mother. The smells and the first words of his childhood allow him to remember to unmistakable accent of joy which then, sadly, was lost along the way. Pain and Glory is the story of the loss of a good. It is possible to return to childhood? Our own desire is reflected in that of the Spanish director: the desire to feel things again, as if they had just been discovered, to know that life is in good hands, like when we were children and we knew that our mother watched over us to protect us. We were children.

The Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, in a letter written at the age of twenty-two which was addressed to the guitarist Regino Sáinz de la Maza, confesses something he considers terrible, which he can only say in secret:

“Now I’ve discovered something terrible (don't tell this anyone). I haven’t been born yet. I’m living on borrowed time, what I have within is not mine; let’s see if I’m going to be born. My soul has not opened at all. Sometimes I believe, with reason, that I have a tin heart!”

Lorca feels that he is foreign to himself and that he lives “on borrowed time”. Luckily, at the same time he wishes to be born again: "we will see if I am born". The lack of this birth makes his heart look like tin, not flesh, it's metal! And he adds: “My soul has not opened at all”. How can one open their soul?

Let us listen to how other acute consciences of our time have perceived this urgency to be born again. The French writer Albert Camus, one of the most committed men of his time, experienced this urgency, which is why he wrote magnificent pages about his birth. He did so in his last work: Le Premier Homme [The First Man, 1995, translated David Hapgood]. The manuscript was found in a notebook that the writer had in his shirt pocket when they extracted him from the wreck of the car in which he died, victim of an accident. Three years earlier he had received the Nobel Prize for Literature. It is surprising that, after having reached greatest scholarly success, he wrote about his humble, discreet, silent birth. Camus, at the centre of European cultural polemics, consecrated by the media and magazines of French intellect; Camus, who had made readers tremble with his stories of the absurd; that same Camus imagines his birth, goes back to investigate the meaning of a beginning. He does so in the portrayal of his alter ego, Jacques Cormery. The opening chapter of The First Man recounts the arrival of Jacques Cormery's parents in a dilapidated house in Algiers. They travel in a ram-shackled cart. The mother was “poorly dressed but wrapped in a large coarse wool shawl [...] with a sweet and regular face, black and wavy Spanish hair, a straight nose and brown eyes, beautiful and clear”. Evening falls and she is about to give birth. Jacques is born. The mother, looking at her new-born son, lets slip a "smile that [...] had filled and transfigured the miserable room". Neither the effort, nor the poverty, nor the strangeness of generating a child in a foreign country can extinguish the smile of the mother to the child, a smile that transfigures her whole surroundings. Thus Camus recounts how he was born. He recreates, with his imagination, his first cry, just come into the world, and the smile of his mother.

Allow me to comment briefly on this. When I read this novel, I was reminded of a conversation between the writer Giovanni Testori and Don Giussani. The book that incorporates this conversation is entitled Il senso della nascita [The sense of birth. Conversation with Don Luigi Giussani] (1) and transcribes the dialogue that Testori and Giussani had in February 1980 on the theme of birth. I compared the dates and thought that Testori would have like to have read Camus' book. He was unable to do so because Testori died in 1993, a year before Camus' daughter printed the French writer’s book posthumously. I do not know if I dreamt it, but I would have liked to have taken part in a dialogue with these three interlocutors on that subject. The conversation of the two Italians starts with the "groaning" of Camus and an entire generation of Europeans who suffer an absence. Giussani discovers the depth of this cry:

“I think that the groan that comes from young people [...] is precisely this absence. It is as if birth were not present; and as if they had not yet reached the consciousness of this dependence. That is to say, of having been wanted. Then the response we give to this identification between pain and hope depends on whether the presentiment of their birth [...] has emerged in them in a crepuscular way; that is to say, the feeling of having been wanted. Because the greatest feeling is that of being wanted. Therefore, their reaction depends on whether or not this presentiment has made its way through the dense clouds”.

Testori also seems to respond to the torn Camus. Testori feels in his generation that “absence, which perhaps is not absence, but melancholy, terrible nostalgia...”

2. “Twenty-four voices with twenty-four hearts”

This desire to be reborn- let us remember Lorca’s expression “I haven’t been born yet” - may hide the insecurity of not knowing who you are, of cruelly feeling a lack of identity. The pain can become so insistent that the desire multiplies and fragments, to the point that you can try to be someone being a hundred thousand, as your Pirandello prophetically said. The search becomes frantic and one claims to be born every moment. One passes from the perception of birth as a gift to a search which is guided by a furious and insatiable will to be many. Having lost sight of the first birth, you try to be born many times. In the morning you are certain people, others at noon, still others in the evening and others, different, at night. Lorca said, in the letter I mentioned earlier, that he himself felt fragmented into a thousand different versions of himself. The selves of the past and those of the future are changing: “There were a thousand Federicos Garcías Lorcas, lying forever in the attic of time; and in the warehouse of the future, I contemplated another thousand Federicos Garcías Lorcas well folded, one over the other, waiting to be inflated with gas to fly without a direction”.

This same impression of disintegration into many faces is found in the music that our young people listen to, sing and dance to. The loss of that feeling of birth, of the unity given by the first heartbeat, makes them break down into fragments. This experience of fragmentation is sung by Switchfoot in their song Twenty Four (2). Everything breaks into 24 pieces, a different thing for each moment of life. They see things as separate and in the end everything seen or experienced (oceans, skies, places, attempts, failures, voices, hearts) must be abandoned to be replaced by the subsequent, unless someone unites the parts.

If we look at our young people, their search has shifted even outside the "I". I sense a generational gap that is no stranger to me. Today we try to be ourselves in the possibilities and reflections that virtual reality offers us. They look for the number of likes that appears under a photo uploaded on Instagram, each new like is a way - or a surrogate - to express a preference. We want to feel satisfied, we want someone to tell us that they saw us in the instant of a photo being taken and uploaded on the internet.

We are living in a period in which it can be said that algorithms can define who we are. Some scientists say they can define us better than we can define ourselves. In the best-selling book titled Homo Deus. Breve historia del mañana [Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow] (3). Yuval Noah Harari asks himself: “What is the I?” and concludes that the calculation of the algorithm allows us to know a person even better than their own partner with whom they live and, of course, better than that person themselves.

Harari talks about a data-centric culture -not theocentric, not anthropocentric, but data-centric. According to this statement we could think that the mystery of the “I”, that vibration that accompanies us from when we get up until we go to sleep, is entirely solved. The calculation of our likes, the collection of our purchases on Amazon, our searches on Google, or the analysis of the photos we upload on Instagram, in addition to the tweets we follow, are already enough material to define who we are. Can it be a response to the theme proposed at the Meeting: “Your name was born from what you gazed upon”? Is the data we leave on the internet enough to express who we are?

Our search for identity takes place between pixels, between forests of pixels. And this is the exciting side of the particular instant we are living: now no longer can anyone take for granted who they are. We search and search again amongst the multiplicity of possibilities. But, then, can we hope that it is a pixel, a point of colour, bright, luminous, that allows us to be reborn, to bring us back to our origin?

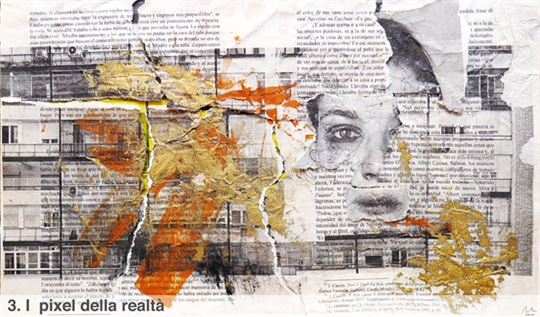

3. What pixel does reality have?

The hypothesis of Modernity - with its variants and declinations - proposed inner reflection in order to resolve the question of identity. One of the consequences of modern failure is that one seeks preference on the internet. The more I perceive my need to be unique, the more I realize that I cannot satisfy this need on my own. In a sense, the evolution from Modernity to Postmodernity, that is, from analysis to the search for an external measure, provokes an interesting change. It highlights a crack in modern research. We want to be preferred and followed. We need someone to tell us this. Let us see if in reality, intensely observed and discovered in its pixels, there may be something worth discovering.

In this sense, the proposal I wish to make is that of Luigi Giussani in the tenth chapter of Il Senso Religioso [The Religious Sense] (4). I personally re-launch this proposal because, for me, it is fundamental to understand who I am. Specifically, I will start from one of the examples that Giussani proposes: that of imagining ourselves at the moment of our birth, when we open our eyes and see things for the first time, but at the age we are today. It is true: it may seem a bit absurd. I, myself, considered it so the first time I read this example: it seemed to me to be an almost ridiculous fantasy. But at the same time I sensed the indication of a different possibility; which, since then, I have never been able to forget. I recognized the acuity of the example which did not leave me indifferent. But then why such did it bother me? The truth is that I had a sense of rebellion against the idea that there was something that existed before me. I felt a sense of rejection towards the order in which the I and reality enter into relationship and discover each other. For Giussani the order of discovery is fundamental and, for this reason, he insists several times upon the subject in the chapter I have cited. Many of you know this book, but let me insist upon it. Giussani, as I have already said, invites us to imagine a new birth. He asks: if we opened our eyes for the first time with the awareness we have now, what would be more important? “Things!”, he says. “I would be overpowered by the wonder and awe of things as a ‘presence’” (p. 100). In other words, to discover the true I, that is, the assemblage of needs and certainties that we are, for which we move, it is necessary that we live the real intensely. This is the first factor, and it comes before the possibility of saying “I”. For a long time, reading this chapter, I said to myself, “Why does he say this?”. When I wake up, I think of myself, of my things, of what I have to do, that is, once again about myself. And Giussani says that things come first. I thought, almost without daring to confess it to myself: “Reality is here, so what? Things are a very beautiful backdrop, - I spoke to myself - but in reality you should overturn the chapter, and start with the definition of the “I” and then see how things are”. As a modern woman, I rebelled against this order and at the same time was a slave to my thoughts, so my “I” drowned too. However, I could not free myself from that example, which always resurfaced by severing my secret rebellions. I began to realize the occasions when what I had in myself and in front of me was saying more about me than any thought. I began to face the things that fascinated me, the things that attracted me and moved me. And so I began to see that “my order" was more thought than real. I began to appreciate the things that dissipated my confusion or made me discover something about myself. It was a matter of verifying the hypothesis proposed by Don Giussani with loyalty. I realized that Giussani's thought represents an anthropological turning point of such stature that it deserves to be examined seriously. In reality, Giussani, today I can say this from personal experience, proposed this work in order to reach that Factor that reveals the unity between the pixels. A Presence that makes things alive and attractive. A grace that exalts the human and allows the “I” to be known in an encounter, without the need to resort to the decomposition of pixels or self-analysis. The first discovery was - and still is - that I myself was a gift. There is no contradiction.

Let me give you two examples, among the many I have collected, in which you can see how this anthropological turning point proposed by Giussani works. That is, how from an encounter with a factor, a “you” present in reality, the “I” emerges.

The first refers to the instance of a university student in Madrid, whose life is recomposed and reborn from an encounter with a teacher. I will quote excerpts of letters written by the student about what had happened to him. "You have awakened the humanity that slept in my person”. He recognizes his truest self: “My heart is what it is because I have known you”. It was not easy to get out of where he came from: "My story is that of a sad and unhappy child who never felt loved”. Stimulated by this awakening, he decided to write her his story:

“The child- he refers to himself – knew very well what fear was, unfortunately thanks to the heavy hands of his father, a poor old man, a military man nostalgic for dictatorship. The boy soon met alcohol and, shortly afterwards, drugs”.

He continues:

“It is complicated to summarize all these years in a few lines, perhaps the enormous amount of litres of tears with which I then soaked the pillow could explain it better than I do. I wanted to shout, shout to express a million emotions and feelings that I could not tell anyone because I trusted no one. That's when I realized that praying was a real necessity, not a mere ritual”.

He tells us about his arrival at university:

“And so I came to university, without really knowing what I was doing there, without wanting to stay there. With a heart full of fear and with the inertia with which I faced things and with much bitterness within me. It was a phase of ups and downs and I began to think seriously about suicide. It's a really hard feeling to see the train arrive every morning and be sure that if I had jumped on the tracks nobody would have cared”.

The student describes his meeting with the teacher as a second birth, that is, as the entering into a place where someone is waiting for you:

“Your office was the only place where I felt completely integrated, where I felt that I was part of something, that, for the first time, someone was counting on me, someone was waiting for me”.

And thus concludes the letter to the teacher:

“I have been alive for twenty-four years, but I have only lived for four years. I, John was born because you, Jane, picked up the letter of a child who, without knowing it, asked for help, you answered this letter and gave him the gift of life, the will to live. For this reason, even if you did not generate me nor saw me grow up, I call you mother.”

The second example is incorporated in a long poem by the Spanish poet Pedro Salinas. It is entitled La voz a Ti Debida [My voice because of you] (5). The poet recounts his experience of love. The encounter with the beloved is an event. It is a presence that has chosen the poet and, thanks to this choice, has brought him out of nowhere:

“When you chose me

- love chose-

I came out of the great anonymity

From all and from nothing” (LXII, vv. 2150-2153)

That moment is well identified with the experience because it can be pin-pointed to a precise date, which marks a before and an after, time changes thanks to that moment:

“It was, it happened, it's true.

On a day, a calendar date

that stamps time upon time” (V, vv. 127-129) (6)

But there comes a time when the poet is fearful and regretful because something so wonderful could get lost or be a lie:

“I hold you

not asking you, out of fear

it may be untrue” (XXXIX, vv. 1397-1399)

These last verses force us to take another step; if we fear the truth of the love we have encountered, if we have doubts about its continuity, how can we discover a lasting love? How can we know its truth? Where and to what reality can one entrust oneself, which can resist disenchantment with distance, disappointment and the passing of time? The student sensed this, and concluded his letter with questions and a desire to seek answers. For his part, Salinas, who felt the distance from his beloved and his fall into the shadows, wondered if there was "another light in the world" (LXIX, v. 2418). Is there anything that can be found and that is not lost, but from which I am reborn every day?

4. The name: a voice on earth, one written in the sky

We turn our gaze to history to try to find this Pixel. Yes, in history there is a man who stepped on this earth and said to his friends: "Rejoice that your names are written in heaven". (Luke 10.20)

He said it on earth, and pronouncing the name of each of his friends also proclaimed an endurance in heaven. Does this phrase matter beyond where and when it was uttered? Does the fact that our names are written in heaven tell us anything? To me, personally, its says that I have been called on earth with an intensity belonging to heaven.

Let us return to the one who promised that the name would be written in heaven: Jesus of Nazareth. He only promised it because he pronounced the names of some men and women while walking in Palestine. And the intensity with which he did so is commented on by Julián Carrón:

“Jesus pronounced their name: "Mary!", "Zacchaeus!", "Matthew!". "Woman, do not weep!"". What communication of himself must have happened in them to mark their lives so powerfully, to the point that they could no longer look at reality, at themselves, without being bowled over by that Presence, by that voice, by that intensity with which their name had been pronounced”. (7)

This means that he called them to earth to begin a relationship with them that was full of esteem. A history so radical as to be destined to reach the sky. Let us dwell on how this way of calling by name is told or, and it is the same, what was contained in that way of calling which brought out the most characteristic traits of each person. Luke talks about a character, whose name has gone down in history for the relationship he had with the Nazarene: Zacchaeus. His story has come down to us. Luke, who recalls the phrase of Jesus "your names are written in heaven", knew that the name of Zacchaeus is among them because his name was heard on earth.

You all know what Zacchaeus' job was: he was a publican, a tax collector on behalf of the Romans. He was rich. For the tax collectors who worked far from Rome, it was easy to derive large margins from the taxes. Zacchaeus lived in Jericho, a small and beautiful city, an oasis in the middle of the desert into which one descends from Jerusalem, surrounded by the oldest known walls. It is adorned with palm trees with clusters of yellow, red, orange and purple dates; it is rich in white and black figs and centuries-old sycamore trees. Zacchaeus was not well liked, he lived in a much more beautiful house than his neighbours. His was not made of mud, he had a stone foundation and it was decorated with Roman capitals. No one wanted to be with him. The rabbis in the synagogue alluded to him when they accused those who extorted taxes from the people. They hurled themselves against all the publicans, inviting them to avoid them. Those who mixed with people like that would be contaminated. All the more so if he fraternized with their leader! The women, who are always more daring, avoided Zacchaeus: the elderly did not hesitate to curse him when they saw him passing by on the street; the married ones looked at him with anger because he was taking half of their husbands' wages; the young women turned around when he greeted them. Even the girls could not stand him, throwing small stones at him to hurt his ankles.

For this reason, it was very strange that Zacchaeus left his house that day, but he was bored of being alone, among servants and slaves. Of course, it was necessary to take the necessary precautions. Zacchaeus was always circumspect: he covered his face with a cloak, entered the temple secretly, to avoid looks of disapproval, sat in the most secluded part of the synagogue, always in the dark corners or sheltering behind the columns.

The night before he had heard from the kitchen staff that the Galilean would pass through the city that day. A man who did wonders. He came from Jerusalem and his fame preceded him. Zacchaeus spent the night awake. Neither the earnings of that day, nor the review of credits managed to distract him. He had everything and nothing. He felt empty. The next morning it was decided: he would go to the square to try to see him. Everyone's attention would be drawn to the Nazarene and he, Zacchaeus, would go unnoticed. He wore a tunic of fabric that was poorer than usual so as not to be recognized. He also covered his head and part of his face. When he walked out the front door, he realized the crowd; it was like a feast day. He followed the current of the crowd. He sharpened his ears. He asked the children for information, covering his face so they would not recognize him. They told him, in the midst of confusion, that the famous rabbi would cross the square where the sycamore trees were. He reached it passing through little frequented streets. Since he was very short in stature, he could not see anything. He smiled as he saw the children playing war by throwing the fruits of the sycamore at each other, he remembered his childhood games. And he had an idea: get on one of those trees. There he could have remained undisturbed and could have seen him comfortably. It was the only thing he wanted: to see Him. He felt a kind of uneasiness. It was curiosity. Lately, he was more and more afraid, he did not feel safe; he even had the garden fence raised so no one could see him. He thought he was a prisoner in his own home. He feared the women, children, and priests of the temple. He did not sleep well. He spoke only to those who flattered him, fearing his power or wanting money. He was surprised at himself, he did not know what he was doing, clinging to the tree trunk, waiting for a stranger who had nothing to do with him to pass by. He felt like a worm. "Maybe - he thought - I'm looking for confusion to forget my fears and my terrible boredom. I am tired of being locked up all the time”. And then, as if responding to himself: "There is no other remedy, seclusion is necessary to keep my money and increase my property...", and he tried to hide his sad expression with thoughts dictated by avarice. At that moment he saw the group of children who preceded his figure. He followed him with his eyes. He was approaching. By now the rabbi was only a few meters away, but Zaccheus could not see his face. The Nazarene walked in silence. He looked intensely at those who approached him, but his gaze did not wander around looking for general consensus. He looked at a little girl. Zacchaeus felt a sense of envy: the master concentrated his attention on that thin and insignificant being, as if she were the only child in the world. No, definitely he who was considered a teacher did not have a generic look. He continued to advance and approached the trunk of the sycamore. Zacchaeus climbed a little higher, rose and moved to the fragile branches that bent under his weight. He wanted to see his face and could not do it from above. At that moment he saw that he was looking up at the branch on which he was hanging. “How strange!” thought Zacchaeus who knew about looks, especially because he wanted to avoid them. He doesn't need to raise his eyes, “he has a lot to look around him and it is not natural for him to stare at the foliage of the sycamore. Raising your eyes at that moment was the strangest gesture you could do. But that was exactly what the Nazarene was doing”. Zacchaeus saw that his eyes discovered him and heard said:

“Zacchaeus, hurry and come down because today I must stay at your house”. (Luke 19.5)

We can imagine what was going on in that little man's head.

ZAC-CHAE-US. Yes, it was his name and that man pronounced it in a way he had never heard before. Not even when he was a child was he called in such a way. Even if that tone of voice had reminded him of his mother's; and the voices of his brothers when they played in the square or bathed in the cistern; and his father calling them in the evening, tired after a day of work in the fields; and that girl who had spoken to him tenderly and whom he had dreamt of for so many nights... The look, the voice of that rabbi had all these things, and even more. He said something profound about himself, as if he knew his recent sufferings, as if he embraced his insomnia and his dissatisfactions. But how did he know his name? Perhaps he had asked the priests of the temple? In that case, he would now have reprimanded him. - But it was impossible: his voice was not severe, but joyful, full of sympathy and affection. His heart leapt. What was happening? He felt his heart full of that music with which the man in front of him pronounced his name. It was as if the walls he had been building for years around his house, and even around his heart, were collapsing. Time seemed to have stopped, he no longer had in mind the fear of the night before, the anguish had vanished. Nor was he concerned about how to protect his wealth so that it would not be stolen from him. There was only that moment. The past and the future, which normally tormented him, had disappeared. That way of saying his name, that Man: “that thing there was everything”, that Man had become everything, the horizon of everything. “Zacchaeus felt invested by that gaze” (8). He uncovered his face, he wanted to see better, identify the traits of the master, see the colour of his eyes. If only he could also perceive his smell! "He was looked at and then saw" (9).

And, moreover, that master wanted to come to his house! Not to the house of the priests of the temple, nor to that of the pious women, nor to that of the disciples. But to his house! To the home of a social outcast, to the home of a foreigner in his own city, to the home of a terrible tax collector! So Zacchaeus came down, without thinking too much about it, rushed down, letting himself be seen and moving away the cloth that covered his face so he would not be recognized. He came down “from the tree and ran home to welcome Him” (10). He noticed that he had an unusual energy, a desire to see more closely, to go towards him, he discovered that all his limbs regained strength and his senses became acute. The colours of things were brighter! Zacchaeus was born again, he was different, he moved in another way. He started walking erect, loose, he did not hide, he even smiled. He went straight home to prepare lunch in honour of his guest. What had changed? Everything and nothing. He carried something inside himself, he walked with a treasure that could not be calculated or accumulated. He carried within himself the “face and heart of that gaze” (11).

So Luke - and a little bit me – recounts how Zacchaeus was born again. That hint of curiosity led him to something that far surpassed what he hoped. Looked at by Someone who gave him a way to see everything else. “In the closed perimeter of his life, the perspective of Destiny had been introduced” (12).

And we come to the conclusion. I invite you once again to use your imagination. Think of what would happen if the interlocutors with whom I spoke this afternoon were here, sitting next to us, willing to converse with Emilia and me, to resume our questions, to cross our truest desires. Imagine a dialogue in which all the things that we carry inside us and that we need appeared; a moment in which friendship becomes more intense and, warmed by sincerity and trust, hearts open. It is not difficult to imagine, because they are like us: Federico García Lorca, Albert Camus, Salinas, the musicians of Switchfoot and Almodóvar are in us, they are like our work companions and our neighbours, like our parents and our children. Suppose that Federico García Lorca were here and now, whispering into our ear that he hasn’t been born yet: “Dear Federico, you can come out of fear and loneliness, you can be born again. Look at Zacchaeus”. Imagine that Camus is crying because he is an orphan: “Albert, I understand your tears, it is possible to be a son. I too cried and someone took me by the hand and made me a daughter”. And if we had invited Almodóvar to the Meeting, I would say to him: “Yes, even at the age of 54 it is possible to live as children, it is possible to depend on a tenderness and a joy in the present”. Let us relive for a moment the intensity of Salinas' love, imagine him talking about the beauty of his beloved for hours and at the end, confidentially, he would tell us, with a shadow of nostalgia, that he wants more: “It is true, Pedro, love awakens in us an insatiable desire for infinity and in this world there is a beauty that speaks of infinity. I live by this love”. And if the Switchfoot group sung us their song, asking for someone to gather its fragments: “Guys, there is someone who by calling us unties the pieces, it has happened to me and now my hours and my days are united because they respond to Him”. They are daring answers, very daring, but I would say them loyally to these friends, not with the intention of teaching something, but letting me the experience of a Presence emerge from me that makes me a daughter.

References

1- L. Giussani e G. Testori, Il senso della nascita, Bur, Milano 2013. Our translation. 2 - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6oCFVGuSyQ.

3 - Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus. A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harvill Secker, London.

4 - L. Giussani, The Religious Sense, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston, 1997.

5 - P. Salinas, My Voice Because of You, W. Barnstone ed. and trans., State University of New York Press, Albany 1976.

6- Moreover, a new gaze is generated in the lover, he is no longer an orphan, he sees everything with different eyes:

There is another being

through whom I see the world

because she loves me with her eyes (XXI, vv. 808-809).

And life is transformed into the constant recurrence of this event, which continues to happen without the novelty fading:

What an immense newness

to go back again,

to repeat the never same

infinite wonder! (LIX, vv. 2074-2077).

This means that the beloved appears as the you that fills the world and gives him the impulse of vibration. What was empty, without colour or consistency, acquires materiality; what was nothing shows, thanks to the encounter, its splendour:

The great empty world

was inert before you: you would

give it its push (XIII, vv. 481-483).

What an enormous first night!

The world! Nothing was made.

No matter, no numbers,

no stars, no centuries. Nothing.

Coal was not black

nor the rose tender.

Nothing was still nothing (XIII, vv. 425-430).

7 - J. Carrón, Disarming Beauty: Essays on Faith, Truth, and Freedom, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana, 2017.

8 - L. Giussani, Qui e ora. (1984-1985), Bur, Milano 2009, pp. 421-447. Our Translation.

9 - J. Carrón, Dov’è Dio? La fede cristiana al tempo della grande incertezza, Una conversazione con Andrea Tornielli, Piemme, Casale Monferrato (AL) 2017, pp. 78-82. Our translation.

10 - J. Carrón, My Heart is glad because you live, Oh Christ, Exercises of the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation, Rimini 2017, Supplement to <

11 - L. Giussani, in Ch. Péguy, Lui è qui. Pagine scelte, BUR, Milano 2009, pp. 96-97. Our translation.

12 - L. Giussani, L’io, il potere, le opere, Marietti 1820, Genova 2000, p. 40. Our translation.

#Meeting19