USA and the Meeting: New Life or Violence?

The recent mass shootings in the United States are the latest in a stream of blood with deep roots that we must look into.“I’m not really motivated to do anything more than what’s necessary to get by.” The preceding statement was written on the Linked-In page of the perpetrator of the shooting in El Paso, which happened on August 3 and left 22 people dead and 24 wounded. With this statement, the killer, Patrick Crusius, said something beyond the anti-Hispanic-immigrant hate that seems to have been the motivation for his insane actions. This, along with every other detail of his life, will be examined by those investigating as they seek to understand, to identify who is responsible for what, and maybe to deceive themselves into thinking they will be able to prevent a similar event from here on out.

Meanwhile, the victims are mourned--both those from El Paso and those from Dayton, Ohio, where only a few hours after, another young man killed nine people, among them his sisters, for reasons which remain unknown. These are victims of armed attacks that follow, in their turn, another rampage from late July in California, where three persons were killed and 12 wounded.

In the end, in less than a week the tragic result is thirty dead and dozens of wounded among innocent people attacked suddenly during normal moments of everyday life. Just in the first half of 2019 there have been 251 mass shootings in the United States, with 136 people killed. Polemics are going haywire on the media platforms in most of the world. There are those that place responsibility on Donald Trump whose anti-immigrant rhetoric, according to some, legitimizes racist hate because, even though there weren’t fewer killings under the Obama administration, the shootings inspired by racial and ethnical hate are increasing. For this reason, Trump was heavily booed by some citizens when he visited the cities where the two latest bloody events took place.

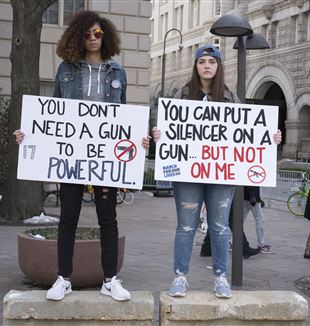

The diatribes are also linked to the perennial theme of gun possession. In the United States there are 120 guns for every hundred inhabitants! How can one drive home to the Americans that a society that is more armed is more violent? Only fifty percent of Americans would want assault weapons to be banned, even if 77 percent retains that mental health checks of gun owners should be more severe. And while newspapers are filled with pages detailing the shootings against groups of unarmed and innocent citizens, there is the risk of forgetting the daily massacre caused by firearms in the streets, between rival gangs, or in domestic homicides. The number of crimes in America does not succeed that of other countries, but the number of victims caused by firearms is sharply higher.

However, all of these considerations cannot let us forget a crucial issue: the particular social and economic context in which these bloody crimes can be situated. After the financial crisis, the inequality between social classes has become ever more acute. The economic recovery has been and remains limited to the profits of the great businesses--financial and not--while salaries and work conditions worsen. Young families are no longer able to remain in big cities. Above all, the American dream that seemed to justify people of different conditions in their hope or illusion of becoming richer, seems to exclude a growing number of persons. The poor and marginalized do not have any more possibilities of emerging, and the young are the victims most aware of the situation.

In this condition in which there is no universal welfare and the right to healthcare is still for many a utopia, to the economic difficulties an ulterior element is added: isolation. Those who are disadvantaged are always more alone. Family ties are disintegrating, as are social and ideal bonds which in many other places in the world help people move forward. One who is alone is always more alone and doesn’t even have that which in Europe grants possibility of sparking a protest: the party, the labor union, an association or movement. No one can share the anger, the solitude, the solidarity, compassion, or even the simple gesture of listening. All of this has its focus: the dwindling of religious experiences that in a land always more violent had motivated and given a goal even to the most limited of conditions. It seems impossible that songs full of hope, like spirituals, were composed by slaves in the worst conditions of life.

And today, where can we find a Mother Cabrini among the many desperate who live at the margins of society? A man alone, without hope, faith, or friends, can find a way to vent his rage in violence against another that he doesn’t know. The firearm seems like the ultimate way to state that one exists. As a beautiful exhibit (“Bubbles, Pioneers, and the Girl from Hong Kong”) that will be inaugurated at the Meeting of Rimini documents, we are in front of a crisis of identity--and not only American identity. The following words by writer James Baldwin provide a key to understand the violence to which we were witnesses in these days: “In a crisis of such proportions, under such a pressure, it becomes absolutely indispensable to discover, or invent - the two words, here, are synonyms - the stranger, the barbarian, who is responsible for our confusion and our pain.”

What should we make of all this? A friend of mine from New York helped me understand how to look at the situation. He told me: enough with analysis. We need to speak again about those positive points from which we can begin anew every day, those realities that often allow us to embrace even the men most alone and desperate, that which makes us intuit that abandoned ideals are not dead and that religion is not the opiate of the people. We need ideals and faith that do not generate closed and auto-referential environments, that don’t claim to stand on their feet due to values, albeit shared ones, that lack life. Communities are necessary, communities in which persons of different backgrounds, origins, and religions can return to living together.