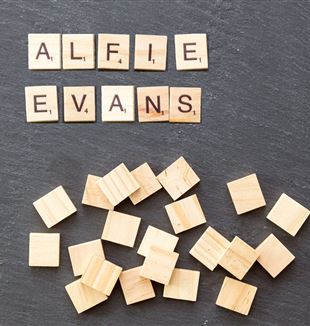

Alfie and the measure of life

They took him off the ventilator and he kept breathing, turning the tables in the legal battle between the hospital and his family, but most importantly, placing us all before inevitable questions.There is an irrefutable fact in the story of Alfie Evans, the child from Liverpool who is at the center of the legal battle the whole world is partaking in: when they took him off the ventilator to begin the “end-of-life protocol,” he kept breathing on his own. He breathed for ten hours until doctors decided to put him back on oxygen. Alfie does not speak, does not complain but he breathes—with or without machines. He lives.

This is a fact which obstinately and tenaciously surpasses the contradictory legal decisions, the comments in the news, and all the wasted words. In some ways, the debate remains complicated, as it often happens when degenerative diseases deemed untreatable collide with human suffering and with the anticipation of those who suffer—especially if the sufferers are a child short of two years and his family.

In these cases, it is nearly impossible to identify definite limits (“up to this point, it’s therapy, but beyond this threshold, it’s obstinacy, etc.”). Consequently, it becomes impossible to speak, to say anything that may surpass the necessary but mere conviction that seems to have lost its evidence—life is and must remain inviolable—and be an adequate response in front of the infinite pain of those parents and the powerlessness of those who wish to help but can’t.

What if, instead, we tried to listen? Alfie is still there, strong and persistent. He breathes. What is his breath telling us?

We find God’s method very strange. He chooses someone who is infinitely small, powerless, and even helpless, to place us all before life’s most crucial issues and to reawaken in us those pressing questions on good, evil, justice, love, and innocent suffering. He does this to clearly show us that life’s scope is much broader than what we can usually measure.

From his bed, simply by breathing and being, Alfie is a companion to us on our journey because he pushes us, he almost forces us, to face these questions. This is the case for anyone who is somehow involved in his story: his parents, his doctors, the judge, the lawyers, those who were set in motion by him, and those who participate in his drama from afar. This makes him even dearer and more precious, if even possible, and it multiplies the efforts to beg, hope, and help him deeply—just like Pope Francis, who was himself set in motion, keeps asking.

Taking Alfie’s company to heart would be enough to derail the ideas we usually have regarding our life’s consistency and its true usefulness: does it lie in what we do, or in the mere fact that we exist, that someone mysteriously loves us, wants us, and is making us now?

Taking his company to heart would also be enough to open a gateway through the pain. Not to explain it or give reasons for it, but to open a gap to the hypothesis that if God allows for such suffering to occur, it cannot be for nothing. This January, in a private audience with the abandoned children of Bucharest, one of the kids asked Pope Francis about suffering. The Pope replied, “Your ‘why’ is one of those that doesn’t have a human answer, only a divine one. … We don’t know the ‘why’ in the sense of the reason, but we know the ‘why’ in the sense of the outcome that God wants to give to your fate. That outcome is healing, and life.”

Less than a year ago, we published a letter on a different child, Charlie Gard, who was in a very similar situation as Alfie. The letter concluded with the following lines, which we are once again proposing because they seemed more useful to us than many other words.

“What is happening is perhaps begging us to delve deeper into our understanding of life’s usefulness, and revealing our inability to answer when it comes to our own lives: when is life “useful?” What makes life useful and, most importantly, useful to whom? Is it enough not to suffer? Deep down, is it truly possible not to suffer?

In order to avoid suffering, we would need to avoid love.

When judging Charlie’s story, we often discuss what would be good for him. But can we detach this good from the recognition—one not so apparent to us—of life’s meaning and its usefulness?

Someone presently wants him and loves him the way he is, and for this, someone is willing to sacrifice oneself. Could it be that this child’s life is useful because of this? If so, could his life be lived out this way? What makes him as profoundly human in his desire for happiness as we who are writing this are? What we desire, and the reason our life is worth living, is that there be someone who wants us now, someone who values our lives and for whom our lives deserve to be given and lived as they were given. Charlie’s parents are this someone, and in their love is the living promise of the love for which his small and shabby heart is still beating.”