Your Holiness, If You'll Permit Me To Respond...

Three long processes which began after the Second World War have led the “community of fate” to a crisis. An internationally renowned legal scholar, European by adoption, explains why.Your Holiness, I’d like to try humbly to respond to your question, which was so simple, so direct, and so “typically Francis”: Europe, what happened to you?

But before answering, I’d like to underline the symbolic significance of the fact that, not only has the Charlemagne Prize been conferred upon you, but that “all of Europe” came to celebrate the occasion. Only a few years have passed since the almost absurd debate in which the proposal of inserting into the European Constitution a reference to Christian roots, along with the tradition of Greco-Renaissance humanist tradition already inserted–a proposal that seemed so natural and, constitutionally, more than legitimate to me–was rejected. It is clear, however, that the soul of Europe, in its values and sensibilities, is rooted in Athens as well as in Jerusalem, and I see in the awarding of this year’s Prize not only a manifestation of love and respect for your person, but also a recognition, albeit a bit late, of this fact.

The two of us belong to very long lines of tradition: your Christian one, going back two thousand years; and my Jewish one, almost five thousand. We are accustomed to look for explanations for the human condition through long processes. And so the response I would like to offer to your question is found in three processes which began as reactions to the Second World War and have progressed over the last decades.

The First Process

For reasons that are quite understandable, the very word “patriotism” became “unprintable” after the War. Fascist regimes (among others), by abusing the word and the concept, had “burned” it in our collective consciousness. And in many ways this has been a positive thing. But we also pay a high price for having banished this word–and the sentiment it expresses–from our psycho-political vocabulary. Since patriotism also has a noble side: the discipline of love, the duty to take care of one’s homeland and people, of accepting our civic responsibility toward the collective. In reality, true patriotism is the opposite of Fascism: “We do not belong to the State, it’s the State that belongs to us.” This kind of patriotism is an integral part of the republican form of democracy. Today, we may call ourselves the Italian or French “Republic,” but our democracies are no longer truly republican. There’s the State, there’s the government, and then there’s “us.”

We are like shareholders of an enterprise. If the directorate of the enterprise called “the Republic” does not produce political and material dividends, we change managers with a vote during a meeting of shareholders called “elections.” If there is anything that does not work in our society, we go to the “directors”–as we do, for example, when our internet connection isn’t working: “We paid (our taxes), and look at the terrible service they’re giving us…” The State is always the one responsible. Never us. It’s a clientelistic democracy that not only takes away our responsibility toward our society, toward our country, but also removes responsibility from our very human condition.

The second process which helps to explain what happened to Europe comes, once again, as a reaction to the War, and is paradoxical. We’ve accepted, both at the national and international levels, a serious and irreversible obligation rooted in our Constitutions to protect the fundamental rights of individuals, even against the political tyranny of the majority. At a more general level, our political-juridical vocabulary has become a discussion of rights. The rights of an Italian citizen are protected by our Courts, and, above all, by the Constitutional Court. But also by the Court of Justice of the EU in Luxembourg, and–again–by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. It’s enough to make your head spin.

Just think about how common it has become, in the political discourse of today, to speak more and more about “rights.” It’s enormously important. I would never want to live in a country in which fundamental rights are not effectively defended. But here too–as with the banishment of patriotism–we pay a dear price. Actually, we pay two prices.

First and foremost, the noble culture of rights does put the individual at the center, but little by little, almost without realizing it, it turns him or her into a self-centered individual. And the second effect of this “culture of rights”– which is a framework all Europeans have in common–is a kind of flattening of political and cultural specificity, of one’s own unique national identity.

The notion of human dignity–the fact that we have been created in the image of God–contains, at one and the same time, two facets. On the one hand, it means that we are all equal in our fundamental human dignity: rich and poor, Italians and Germans… On the other hand, recognizing human dignity means accepting that each of us is an entire universe, distinct and different from any other person. And the same is true for each of our societies. When this element of diversity is diminished, we rebel.

The third process that explains what has happened to Europe is secularization. Let me be clear: this observation is not an evangelical rebuke. I do not judge a person based on his or her faith or lack thereof. And even though, for me, it’s impossible to imagine the world without the Lord–The Holy Blessed Be He–I also know many religious people who are odious and many atheists of the highest moral character. The importance of secularism is in the fact that a voice which was at one time universal and ubiquitous, a voice in which the emphasis was on duty and not only rights, on personal responsibility in the face of what happens to us, our neighbors, our society and not the instinctive appeal to public institutions, has all but disappeared from social praxis.

This process also began with World War II. Who among us, after having seen the mountains of shoes from millions of assassinated children at Auschwitz, didn’t ask the question: God, where were you? And please forgive me, your Holiness, if I say that I’m not sure that the Church, from the time after the War up to the Council, did not in some way exacerbate this crisis of faith.

It has taken decades for these three processes to mature and produce now their “sour grapes” (Is 5:2). We see the impact everywhere, not least in matters regarding the European Union.

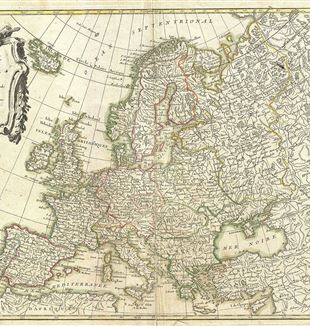

Beyond its economic purposes, the EU was conceived as a “community of fate.” Our fate as Europeans, determined by our history–horrendous and noble–by the values we’ve inherited, by our geographic and cultural proximity, required a reciprocity, a responsibility and a solidarity that went beyond standard international relations. I do not want to preach a sermon about peace, but simply would like to observe that this peace, in Europe, is different: it is a peace based on forgiveness and humanity, not only on interests and guarantees.

But today? The EU has become something entirely different. Perceived as a threat to national identity, it has become a union of interest’s, of calculating advantages and disadvantages. Of solidarity that is present in times of prosperity, when it is not put to the test, but disappears in times of need. A union of rights, but never of duties. Your Holiness, I’ve only been an Italian national for a little while. This could be why I am not embarrassed to call myself an “Italian patriot” and to love this country that has adopted me. And being Italian, I must also be European. I will not lose hope, because, whether we like it or not, we are in a Europe that is a “community of fate”. What that fate will be depends on us. For better or for worse, we cannot help but call ourselves Europeans.