We Are What You Are

In Madrid, in September 1985, at a dinner among friends, someone asked “Why don’t we become one?” A few days later, the Movement flowed into the river of CL. Here is the story (told by the protagonists) of a moment that has marked our history.In the mid-1970s, while in Italy Fr. Giussani was forming an increasingly tight bond with a group of university students, another story began taking shape. On December 22, 1974, in a Milan restaurant, Giussani met a young Spaniard, José Miguel Oriol, who belonged to a prominent family responsible for a publishing house, ZYX, the expression of a group of leftist Christian laypeople. This was the Franco era. In October of 1970, at the Frankfurt Book Fair, Oriol had met Sante Bagnoli, director of the Jaca Book publishing house, linked to the Movement of CL. They continued to meet over the years until, in December 1974, Oriol received an invitation from Bagnoli to dine with Fr. Giussani. At the end of the dinner, Oriol thought, “Here, Christ is spoken of as a real presence.” Those words reconciled all his previous history: breaking off from his family, his work with the poor, his political struggles…

Thus, in February 1975, a Renault crossed Spain and reached Milan, with Oriol and his wife Carmina, José Antonio Garbayo and his wife Teresa, and Jesus Carrascosa (known as “Carras”).Giussani’s first trip to Madrid was in December 1976, and then starting in 1978 he traveled regularly to Spain.

The first encounters. In the spring of 1978, having left ZYX and the group connected with it because of irreconcilable differences, Oriol–with his wife, Carras, Fr. Malagón, and a friend–founded a new publishing house: Encuentro. This was the origin of the second phase of the history of relationships between Giussani and Spain, with consequences that nobody could have foreseen.

Everything happened by chance. It was a period of great upheavals–ecclesiastical and political. In 1975, General Francisco Franco died, and Spain began to move toward democracy. Signs appeared of a cultural shift that would erode the Catholic tradition, partly due to the difficulty of receiving the contents of the Second Vatican Council, a vertiginous crisis of vocations, and the tendency of a certain kind of theology to take on radical positions and attitudes. In this context, a group of young priests, formed in the school of Msgr. Francisco Golfin and Fr. Mariano Herranz in the Madrid seminary, began to work in some Madrid parishes. They wanted to remain friends and help each other, above all in their work with children and adolescents. Over time, some of the young people involved in those initiatives began to ask for something more from their priests, among whom were Javier Martínez, Javier Calavia, Julián Carrón, and José Miguel García.

In the meantime, in October 1978, Oriol prepared a four-page advertising folder with Encuentro’s editorial program. It reached the hands of a young man involved in the Cursillos de Cristiandad, Carmen Xilio, and he, in turn, showed it to a young priest friend, Carrón, who gave it to Martínez, who had heard of the CL Movement in Germany, through a fellow student at the University of Frankfurt, who had met CL through a Swiss student. Martínez and Carrón, having read the Encuentro program, were struck by the list of publications, and asked who in the world these people could be. Their group, too, had in mind an editorial project to publish in Spanish authors such as Péguy, Bernanos, Claudel, Von Balthasar, De Lubac, and Guardini. These very writers and theologians were featured in the Encuentro program. They contacted Oriol immediately, and had their first meeting in January 1979, during a dinner at the Carras home. Their communications and meetings continued through June, with a dinner that proved decisive: “We started at 9 pm, and we continued talking until 3 in the morning, eating sardines,” recalls Carras. “The next day, Martínez was to depart for the U.S., but we were having such a good time that we never went to bed!” Javier Prades was one of the participants in this meeting. At the time, he was a 19-year-old law student. “Martínez told me, ‘This evening, don’t make any plans, because I want you to meet some people I’ve encountered.’ We arrived in Chabolas, a very poor area on the periphery of Madrid. When we entered the house, we were struck by the order, the beauty, a sense of life and contentment that clashed with the surrounding environment.” Leaving, he carried away the impression of an “unexpected correspondence with our sensibility and desire for faith with people who lived in conditions that were very different from ours.” After Martínez left for America, Calavia and Carrón continued to guide those young people, while Martínez followed the evolution of their relationships from afar.

A paternity for everyone. In the meantime, the young people linked to those priests became increasingly aware of a growing stability in their friendship. They met and listened to Giussani many times in Madrid, and the bond with Carras and the Oriols strengthened. A collaboration with the Miguel Mañara Cultural Center began, and some friends returned from the Meeting of Rimini enthusiastic. It was a period of searching, conversations, and encounters.

Carrón recalls that “the more we came to know the Movement, the more we moved closer to its expressions, its gestures, its documents, the more this passion grew, the desire to share relationships more deeply, the verification of this fascinating modality of living the faith that we had encountered. Fr. Giussani surprised us with a paternity that we had never known before. He wasn’t there to measure us; so then we realized his preference.” In the end, this “spread to everyone; it broadened the paternity of everyone as well as the desire to embrace the diversity of the two stories.”

In 1982, they made the first attempt to do something together. In October, CL and the inter-parish group decided to organize a pilgrimage together to Avila, on the occasion of John Paul II’s first visit to Spain. “It was a failure,” recalls Prades, “because there were so many differences between our ways of doing things and those of the kids of Carras.”

After this attempt, however, the priests continued to maintain their relationship with CL, but for several years there weren’t any common initiatives. “It was only the faithfulness of our priests, together with a few personal attempts,” that continued the story, recalls Prades.

Toward the mid-1980s, that inter-parish reality became an association, calling itself “Nueva Tierra.” At a certain point, some of the young people urged for membership in CL. Among the priests, Carrón saw this hypothesis as a natural consequence, while others resisted for reasons of prudence, asking for more time. The internal debate lasted until 1985.

The Avila meeting. One evening in January 1985, Oriol saw in the Nueva Tierra headquarters a flyer pinned to the wall, and noted that it was just the same as those of CL. It was written by Fernando De Haro, a young man from Cordoba who since 1980 had been participating long distance in the experience of the parish groups created by the Madrid priests. The flyer was entitled, “A Proposal,” and said that those young people “claimed to be a way of making present a proposal of Christian life in the spheres where women and men live” and that “Christianity is not a superimposition on the human, but it is its definitive fullness and depth. Jesus is not just the definition of God, but also of the world and of man. The salvation we live not as the sum of individual and intimately personal liberations is given to us freely in Christ.”

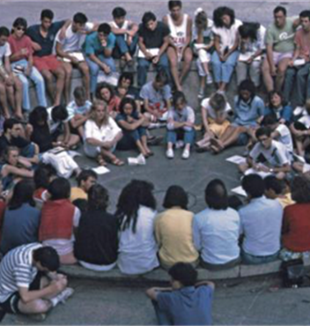

The meetings intensified. Giussani himself had a dialogue with the priests of Nueva Tierra. At the end of May, about 50 people of the two realities gathered in Oriol’s house, and they thought of making a unique proposal to the young people of CL and those of Nueva Tierra: why not take advantage of the occasion of the summer course planned for that July? Therefore, Giussani was invited, and July 22-24, 1985, he participated in the “Tenth Encounter of Avila.” The Avila gatherings involved two weeks of shared life in study, prayer, culture, and celebration. Giussani concluded his talk there with these words: “We are what you are: our story and your story have the same roots, the same principles, and an identical purpose. Today, what is most needed in the life of the Church is precisely this: that there arise a movement that corresponds to the life of each person, a great movement of friends engaged on the basis of the circumstances of their lives. A great movement in which faith returns to being what it was in the first centuries: the discovery of a more human humanity. Man alone cannot be such. Only with Christ can man be a man. Here you call it Nueva Tierra. What does Nueva Tierra mean? New humanity. What does it mean to say that Christ is Redeemer? That without Him, man is not man.”

According to Carrón, Giussani had a very clear idea that “the final goal of the faith is precisely to generate a New Land, but also that the journey to reach that goal demands a method and an awareness of the nature of Christianity that CL had with greater clarity than what we still desired. Without the companionship of Fr. Giussani, we would never have reached understanding of what it means to live the human experience and the faith, the New Land we desired.”

In Avila, De Haro ended up sitting next to Fr. Giussani at dinner and told him about the Cordoba flyer. Giussani asked him for it, and the young man ran to his room to get the text. Giussani read it and said, “These are the same things we say.” The conversation continued and De Haro complained about the fact that there were still only a few of them in the group. Fr. Giussani interrupted him: “This doesn’t matter; what matters is the life among you. We, too, were few in the beginning. You will become many.” That evening, in a park in Avila, many of the friends gathered for an hour to share and contemplate the words Fr. Giussani had used in the lesson to explain what the encounter with Christ implicates. José Luis Restán, at the time one of the young people of Nueva Tierra, recalls that “listening to Fr. Giussani speak about Christianity and describe the experience of CL, to many of us it seemed that the journey was smoothing out and becoming clearer. To think of doing something ‘on our own,’ inventing an autonomous form when we had before our eyes a charism recognized by the Church, in which we recognized ourselves in such a simple and passionate way, would have been absurd.”

Issue Number 0. One evening in September 1985, the Carrascosa’s hosted a dinner for some leaders of CL and Nueva Tierra. The conversation focused on some observations of the friends of Nueva Tierra, until Oriol spoke up and renewed the question, already asked in previous months, about why they should continue with two distinct movements, and whether the time had come to make of the two one thing alone, following the charism of Fr. Giussani. “We discussed it all night long,” recalls Carrón.

After a few weeks, on September 28th, an assembly of the Nueva Tierra members decided by majority to join CL. Carrón recalls that “this passage was accompanied by Fr. Giussani. Without his paternity, the journey would have been much more of a struggle. With him, we were able to face the difficulties and differences of a human journey.” In the end, “this paternity won out over all the difficulties and objections that arose during the journey.”

Calavia, in the September 1985 “Issue 0” of Nueva Tierra, revista de Comunión y Liberación, wrote, “For me, the challenge is to live the Movement, and this involves accepting others just as they are. The greatest problem is self-love, the lack of respect for differences, hasty judgments, schematic thinking, vanity, and the anxiety to be in the limelight. These are the obstacles. The differences aren’t a problem; they’re overcome immediately. There are things that took years to understand, and now they’re understood in five minutes.”

The rest is the story of an uninterrupted unity.