In the Heart of Africa, at the Foundation of Man

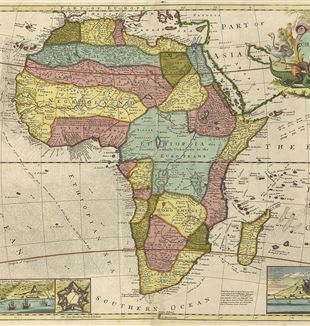

A journey to the CL communities in Uganda, Kenya, and Nigeria, where a contagious vitality is creating a new humanity.UGANDA

Cholera

The effort had not been a small one. Forty cement parts, each weighing over 300 pounds, had been transported one by one along a precipitous, rough-hewn road to a far-off village on Lake Albert, the impassable border between Uganda and Congo. But in the end, the two artesian wells were built. They worked, and there was a great celebration. Six months later, returning for the periodic check, there was not a little surprise to see that nobody actually used them. Yet it had been a well-considered choice: cholera was widespread in that area, and the use of the lakeshores as both latrines and water source created a deadly cycle that it was imperative to break. “But the lake water tastes better, and it’s easier to draw; we’ve always done it this way!” The day after, a truly great reason was needed in order to begin again, big enough to embrace even the absurdity of that way of living, and the obscurity in which, in any case, they, too, harbored a desire for a beautiful, just, and happy life; maybe just an “uncultivated” desire. This great reason shone visibly in the face of the person telling this story.

The “Three Steps” Club

All of a sudden, he was sitting in front of me. I had been looking at the sky, which, in Africa (unlike Lombardy, where it happens only rarely) always draws your attention. He was dressed in rags. I thought that his world must be limited to the exquisitely cared for garden, the courtyard with the dogs, and the gate, always ready to open it wide every time a “friendly” car arrived. “I believe I know you,” he said. “Your name is Pier. We met in Kireka; I’m one of Rose’s kids.” Yes, of course, we had already met, you’re right, and I got ready to waste a few minutes with the pleasant, semi-illiterate young man. But he continued right away, firmly, “Listen, in School of Community, when it talks about the human factor, I realized that it really is decisive in my experience…” And so, flabbergasted and laughing inwardly enough to split my sides, I found myself going over the texts of our life with the fresh and sharp questions of Jimmy, not even 20 years old, one of the young people of the “Kireka Three Steps” Club, in the Kireka slum of Kampala, Uganda. At the end, he also demonstrated his skill with the adungu, a small “Davidic” harp on which many young people here are virtuosos. Just a few weeks before, 180 of them had been on an outing with Rose!

Human Rights and the Meaning of Life

Clara, Giovanna, and Kizito recount: We brought The Risk of Education to schools, slums, and prisons in Uganda, and, everywhere, people reacted with great enthusiasm. One of the courses was in Luzira Prison in Kampala, the biggest in Uganda (about 1,500 prisoners), where we held six weeks of formation on The Risk of Education for nine new social operators. At the end, during the ceremony awarding attendance certificates, the commanders of the Prison Training School (the section of the prison responsible for the formation of staff), having heard about the course from the social operators who had participated, asked us to continue to follow the new employees, to help them form all the prison personnel (about 600 people) and to think about a meeting for the prisoners as well. They told us that until now they had heard at best about “human rights,” but what we were saying went much further, and is exactly what the entire society needs.

KENYA

Five Schools, with Passion

Five schools: a nursery school, two elementary schools, a technical vocational school (the biggest), and a high school that has only recently opened. This is the surprising way that the presence of the Movement has developed in Nairobi. Each school also hosts social programs for children and families. Similarly surprising is the testimony of unity during the meeting with the local (the majority) and Italian directors of the schools. St. Kizito is the professional school that initiated our presence in Kenya, begun at the invitation of Fr. Marengoni, a seminary companion of Fr. Giussani, and greatly amplified through AVSI programs. “Emanuela Mazzola” is the nursery school of the parish of the St. Charles Borromeo Priestly Fraternity. The “Carovana” primary school is run by the Urafiki Foundation, formed by adults from the St. Charles Parish and some Italians. The “Little Prince” primary school is at the edge of the Kibera slum (900,000 inhabitants, the biggest slum in Africa), founded through AVSI, with a local director and vice-director, and an Italian presence in its management. The “Cardinal Otunga” high school is the latest arrival (this too, thanks to AVSI), and is also directed by an Italian-African team. There is unity within each school, and unity among the schools, all striving to put into practice the education that Fr. Giussani said is the reason for the Movement’s existence. The most beautiful thing is to see how these people, speaking about their own work in the school, are actually talking about themselves and the discoveries and changes that have happened as the experience has proceeded and the unity among friends has deepened, all from within a life. No less passionate is the work of COWA (Companionship of Works Association) and many adults who help young people enter the workplace and attempt micro-entrepreneurial ventures. What interests us is life.

NIGERIA

Life amid death

The small Christian minority living in Maiduguri, in the Hausa territory in the north of this immense country (“the giant of Africa”) suffered over 50 deaths. Forty churches were burned, including the Bishop’s residence, and a Catholic priest was murdered. Everything had been planned in the mosques during “Friday prayer.” There was no intervention, no inquiry, no responsibility. When the mangled corpses of the victims were returned to the city of Onitsha, in Igbo territory in the eastern part of the country, which is prevalently Christian (the Biafra of the attempted rebellion, massacres, and starvation of the 1960s), a manhunt for northerners ensued, with scores killed barbarously, thousands forced to flee, and two mosques set ablaze. The Council of Christian Churches condemned the murder of the defenseless and the destruction of the property of Christians that has been happening for years, and denounced the extremists who have “the full backing and support of influential Muslims who have never learned to appreciate the value of living together in peace.” It added that the Council “may no longer be able to hold back its own restless youth, should this evil and sad tendency progress any further.” The Episcopal Conference denounced the lack of response by authorities who knew in advance, the absolute lack of inquiries and investigations of the guilty, and the absence of any public mourning. “We ask all Christians, especially our brothers and sisters of the North who have suffered for so long, to remain faithful to Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace. We encourage them to constantly battle by all constitutional means to affirm their right as free citizens of a democratic Nigeria to establish and practice their own religion fully, anywhere in the nation. We beg them to avoid all violence because it is incompatible with the Christian faith and all authentic religion.” The first pages of the newspapers are all dedicated, however, to the Niger delta and the Ijaw revolt, with nine Western dependents of foreign oil companies kidnapped. There, it is not certain whether a human life is worth more than a barrel of oil.

Educating to reality

In Lagos (over 15 million inhabitants), only half of primary-school-aged children attend, while only a fifth of those between 12 and 17 attend middle or high school. A great number live on the streets, exploited or committing all manner of crimes just in order to eat. Studies emphasize that lack of guidance and economic support are the principal causes of this situation. But what also counts is the dominant mentality that says a person’s worth lies in his ability to have money and power (however small). The problem is not just the inability to attend school. The CLU students of Lagos affirm that an attentive look at the situation shows that there is no real tie between the education given and the reality one lives. This is why “any attempt to help these young people without realizing the need for an education that introduces them to a relationship with reality would be grossly inappropriate.” No sooner said than done, starting with 120 youngsters between 6 and 14. For the university students, with the university closed for the umpteenth time, it is an occasion for charitable work in the sense that the Movement has taught us, that is, a verification, above all for oneself, that the need is the occasion for realizing what constitutes us, for sharing it, and in this way helping ourselves and educating ourselves to the real stature of our humanity. The Episcopal Conference told Catholics after the events of Maiduguri, “Let us never tire of combating evil with good and sowing love where there is hate.” For the Lagos CLU, it’s possible.