On a journey with McCarthy

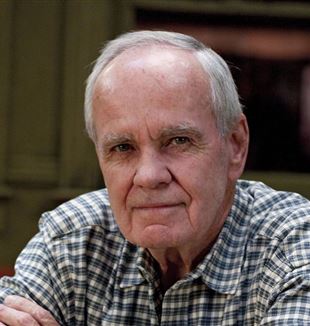

The great American writer who gave the title to this year’s Rimini Meeting, as recounted by Stas’ Gawronski, author and TV host. From the October issue of Tracce.“Look, at a certain point, I literally found myself on my knees before the mystery. Literature has this power: it takes you deep down to the bottom of reality, and of yourself. It does not happen often, but it happens. And it happened to me with Cormac McCarthy.” So much so that, when he talks about it, he is often moved. He has to stop, weigh his words, pull them out of the depths of his experience. This also happened to him at the Rimini Meeting, which this year took its title from a novel by the great American writer: “If we are not after the essence, then what are we after? And on stage in Rimini, retracing McCarthy's journey in search of this “essence” was Stas' Gawronski. Author and TV host, creative writing teacher, was the protagonist (alongside critic Alessandro Zaccuri) of one of the most intense meetings of the Rimini Meeting , which had a profound impact on him ("I stayed lonely for a short time, but I was especially struck by the freshness of the young people. I want to go back and experience it longer, because I think the Meeting must be lived by listening and allowing yourself to be touched") and opened wide and deep horizons for those who got to know him.

Can you tell me about your encounter with McCarthy? Because it is evident that he somehow became your friend, your companion on the journey. How did that happen?

When an author strikes me, I read and re-read their works several times, because it is like digging in the earth for a spring whose presence you feel. That is what happened with McCarthy. Encountering him prompted me not only to read all his books, but to linger for a long time, early on, on the ‘The Border Trilogy.’ It reached the point where I wanted to re-read those novels by traveling to the places he writes about. McCarthy's geography is real: he is absolutely precise in contextualizing his stories, in time and space. So I took two trips along the border: in 2014, on the U.S. side, and two years later, in Mexico. We would often read passages together with locals, telling them this story as if it were real and asking directions to the places described. The reactions were extraordinary: McCarthy's words touched their imagination and came back to invest us. It was a way to delve deeper, into the very guts of the text. Until the moment I realized that something had happened. With an author like McCarthy, words can take you so deep into reality that you find that something inside you has bent, and you find yourself on your knees.

Are you referring to a physical, specific moment? Or is it something that has developed over time?

No, it is something that came out over time, but has then repeated itself in various re-readings. It still happens to me if I re-read certain pages: the experience is always new. One might say, “yes, I've read it, I know it,” but something unpredictable actually happens every time. For example, at the Meeting, I experienced this when I read the page about Alicia Western, the protagonist of Stella Maris and The Passenger, who imagines giving herself up to the animals around her, and when I uttered the word “Eucharist.” Something inside me moved. It is inexplicable. But one thing is certain: McCarthy's words are incarnational literature. They give flesh to the foundation of everything.

When did you realize that the entire journey of his novels could ultimately be read as a single story, a single journey, as you described at the Meeting?

When I read The Road, in 2007, I clearly felt a sense of arrival. It became evident that the protagonist of McCarthy's earlier stories is a man who travels in the wake of a profound longing for a relationship with his father, whom he has lost. And this father is God, the divine: He is the one sought after by his characters, and in the outcome of The Road, He is a divine presence that is embodied in a relationship. When I was confronted with this burning reality, the relationship between the father and the son who together guard the fire – that is, the substance that the protagonist of McCarthy's stories has sought in all the previous novels – then the design of this truly unique story became clear to me, of which The Passenger and Stella Maris are a fulfillment. By analogy, I would say that The Road relates to the New Testament as all the previous books by McCarthy relate to the Old Testament. In The Road, the revelation of what this wandering protagonist, often bewildered and lost, goes in search of is fulfilled: there he finds his essence.

What are the traits of this protagonist, the “hunter of the divine,” you spoke of in Rimini?

In All the Pretty Horses, there is a passage that says a lot: “What he loved in horses was what he loved in men: the blood and the heat of the blood that ran them. All his reverence and all his fondness and all the leanings of his life were for the ardenhearted.” So, at the beginning of all of McCarthy’s stories is a man with a burning heart; and this burning heart is not an expression of vitalism, of the enthusiasm and strength of youth, which often remains superficial. No, at the beginning there is a heart in which a divine presence dwells: there is a fire that makes it burn.

And it has the same nature as the divine, that is, as the object of its search...

Yes. This fire desires to reunite with a fire that exists outside of itself. Think of the protagonist of The Crossing, for example. He is a boy who experiences a kind of epiphany at the moment his gaze meets that of a pack of wolves. They lock eyes. And there is a recognition between the fire within the protagonist's heart and what passes, like electricity, through the eyes of these wolves. The boy is marked by it; it is as if he is being touched by a searing iron. From that moment on, his only desire, his obsession, is to possess the divine. To possess this experience that allowed him, for a moment, to experience the fullness, the communion and infinite beauty he will seek.

And this burning heart is irreducible, it continues to burn no matter what happens on the journey....

Yes, it is absolutely an irreducible point. But the mystery of freedom is great. The man who becomes a hunter of the divine, like McCarthy's protagonists, is tempted precisely by possession, that is, by the idea of possessing that mystery. When that happens, his adventure becomes a descent into hell. Everything turns against him and he goes astray. That is the moment of a second temptation, more decisive still: the belief that there is no foundation to reality, that this divine ultimately does not exist. The man who arrives here succumbs to the temptation of nothingness. He remains a hunter, precisely because of the irreducible presence of this fire deep within his heart, but he becomes a hunter of men, a man who devours other men. We see this in the cannibals of The Road, as in the scalp hunters of Blood Meridian.

The other condition experienced in this journey is “being an orphan.” What is the weight of this condition and what does it does it tell us today? Perhaps it is one of the words that illuminates the present the most...

The point is that we are all orphans until we agree to enter into a relationship with the father. At the Meeting, we were talking about the scene in The Crossing in which the old hunter says to the boy: look, you cannot catch the she-wolf – which represents the divine: “The wolf is like the copo de nieve. Snowflake. You catch the snowflake but when you look in your hand you do not have it no more.” The orphan is someone who stubbornly wants to seize the divine and, slowly, slips into a drift of nihilism. And McCarthy is very good at describing the radical, cosmic loneliness experienced by the hunter of the divine, who is unable to recognize his own orphanhood and, therefore, of entering into a relationship with his father. Thus, the orphan does not know that he is an orphan; he does not come to that awareness that, despite loneliness, could allow him to open, just as Alicia Western opens up. She, too, is a lonely woman, but her attitude is not one of possession; rather, it is a gradual, but radical, abandonment of everything she could possess. It is a paradox: the divine reveals itself to us through things, through the experiences we have, people, but He does not allow Himself to be possessed. On the contrary, we encounter Him when we understand that the step to take is, in some way, to lose one's life, to offer it. But still, it is the relationship that McCarthy describes very well in The Road between Father and Son.

The “temptation of nothingness” leads to nihilism, which McCarthy is also often accused of because of his stark and unflinching way of depicting evil. But is this really the case?

It is clear that for McCarthy, life is a battlefield in which an epic clash between light and darkness takes place. This is very starkly described: there is a struggle between what is human and what is not. Evil is a spiritual reality that expresses itself through very precise personalities, such as Chigurh, the serial killer in No Country for Old Men, or Judge Holden in Blood Meridian. But at the same time, the description of this conflict is like the tale of two fighters whose bodies adhere almost to the point of becoming one being: light and darkness are inlaid, coagulated. To the point where the darkness itself, somehow, emanates light. In Rimini, I was quoted certain paintings by Rothko, black but luminous canvases. Can darkness emanate light? Yes, if we think that Christ has said, “When I am lifted up, I will draw all men to myself.” Here, McCarthy seems to continually invite us to fix our gaze on the cross, to drink deeply from the bitter cup of the nonsense of what he clearly writes in The Passenger: all reality is loss. If we are not distracted, if we fix our gaze on this loss, then perhaps there, at the bottom, we can catch a glimpse of light. And that light is the essence on which all of McCarthy's literature is grounded.

The opening page of The Passenger, with which you began the journey of the Meeting, where Alicia hangs from the tree from which she hanged herself, is fierce. What impact did it have when you first encountered it?

It was powerful because I felt like I was there. McCarthy is often paradoxical, but that page tells us that where evil is extreme, where the scene is one of death, the essence is present. And that is the very paradox of the cross. As he had already said in a passage from The Road, “All things of grace and beauty that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth in grief and ashes.” There can be no happiness that the hunter of the divine seeks without sacrifice taken to the extreme. And we readers are invited to plant our eyes on this mystery. Days ago, at the end of a meeting, a young man told me he was going to read McCarthy, but not The Road, because he found it too distressing. I instinctively replied, “But that's blasphemy. It's like saying, 'I accept everything about Christ, but I don't accept the cross because it is too distressing."”

Read also - Curran Hatleberg: The shock of the other

As a reader, have you encountered other such powerful authors?

Yes, but I have to mention names like Dostoevsky or Manzoni. Or, for the impact she had on me, Flannery O'Connor. She is another who, when read, reinforces the perception of mystery. She, too, is disturbing, not an easy read. However, if you experience it fully, if you accept to engage with the text, it is a literature that shapes and gives form to the burning of our hearts.

Ultimately, has this years-long journey with McCarthy changed? If so, how?

Definitely, as in the title of the Meeting, it is a journey toward the essence. Think of The Road: it tells of a reality in which nature has been reduced to almost nothing, the world is ashes, it is dark and cold... But there is the essence, which lives in the relationship between father and son. The same is true for the protagonists of The Passenger and Stella Maris. In their journey, there is a stripping away of everything superfluous to get straight to the heart. So, if McCarthy's literature is having an effect on my life today, it is just that: helping me on the path toward the essential. Indeed, “toward the essence,” as he would say.