What no power can take from us

If life is totally given, even a person deprived of everything can never be a slave to any lie. The relevance of the lesson of Aleksandr Solženicyn quoted by Fr. Giussani in the eighth chapter of The Religious Sense.One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovič and Matryona’s House, The Gulag Archipelago and The Red Wheel: the infinitely small in his first two stories and the infinitely large in the two powerful historical portrayals in which Aleksandr Solženicyn reconstructed the history of the Soviet concentration camps and that of the 1917 revolution with the drama that preceded it. However, in his two short stories, the great Russian writer (Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970) told the story of a man and a woman whose greatness and dignity he allows us to rediscover. On the one hand was the astonishing greatness of Ivan Denisovič, a simple inmate of a Stalinist camp who had managed to preserve his freedom and his soul even in a lager, a place made especially to destroy humanity ("you must be glad to be in prison," another inmate, who like him had not succumbed, told him, “Here you have plenty of time to think about your soul"); on the other, the unimaginable dignity of Matryona, a poor peasant girl whom everyone considered stupid and whose past was not at all blameless, and who instead, after death, had revealed herself to be "the righteous without whom neither the village nor the town nor all our land lives."

Quoted in the eighth chapter of The Religious Sense, where Fr. Giussani makes us grasp the tragedy of a man who, having lost the "totality of his factors," loses himself, Solženicyn instead documents the possibility of resisting power, in its most extreme form, that of Soviet totalitarianism. The writer had come to know it from the very beginning (he was born in 1918) and it would mark his entire life, at first fascinating him with the dream of a new world, then repelling him through its murderous violence, then turning him into its die-hard opponent (eight years in the camp starting in 1945, exile after 1974), ending up succumbing.

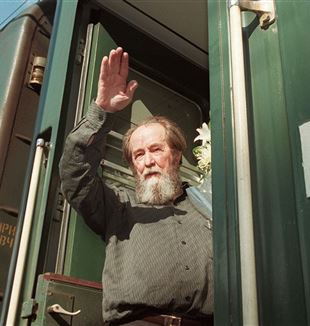

Solženicyn, on the other hand, would outlive it, returning to his homeland in 1994 and witnessing (until his death in 2008) his arduous journey towards incomplete democratization.

Just as he had witnessed the irreducible nobility of the seemingly mostly insignificant individuals, Solženicyn had thus also been the observer of the great history, where he had seen the attempt to destroy humanity right down to its roots and was able to recognize and denounce the instruments with which the regime had tried to bring this ideological project to fruition, as evoked by Giussani in quoting Solženicyn: "The spiritual forces of Shakespeare’s evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses. Because they had no ideology … thanks to ideology, the 20th century was fated to experience evil doing on a scale calculated in the millions."

It was precisely the overcoming of ideology through the rediscovery of the infinite nature of reality "not made by man's hand" that had been the guiding path for Solženicyn to rediscover the good meaning of being in the midst of the tragedies of the century and of his own personal existence (in addition to revolution and war he also had to overcome the ordeal of cancer).

His intuition that there was a good meaning prompted him not to break with the past, to use an expression of Fr. Giussani, or, to use Solženicyn's formulation, to study history and espouse "the fate of the contemporary Russian writer concerned with truth: it was necessary to write only so that all this would not be forgotten, so that one day posterity would know it," because only by judging was it possible not to fall back into the same tragedies of the past but to discover a surprising richness within the human, who knows how to overcome "the hateful division of the world," as St. Sergius of Radonež, one of the great Russian saints, had called it.

It was perhaps for this reason, because of this victory over division, that Matriona discovered herself to be "righteous". Not because of her own merits, but because she was “misunderstood and rejected by her husband, a stranger to her own family despite her happy, amiable temperament, comical, so foolish that she worked for others for no reward, who had buried all her six children, and had stored up no earthly goods.

After all, the first step of any totalitarian system is the atomization of society because only a people made up of isolated entities can be easily subjugated and be deprived of the reference points, of the relationships that enable them to resist the pressures of any regime, giving them a bulwark to share with their fellow human beings and from which to face the attacks of power and the demoralization of a person who, like Solženicyn deprived of a non-relative truth, found themselves at the mercy of their own loneliness and arbitrariness.

Read also - The courage to return

The person who is no longer alone, who rediscovers their own meaning, totally given (just as the life that Solženicyn found after every trial was totally given), thus rediscovers something that can no longer be taken away from them by any earthly, relative power: a person deprived of everything can no longer be deprived of anything and rediscovers that they are free. They have the strength that they cannot give themselves on their own, which, if acknowledged, becomes invincible: "Even if all is covered by lies, even if all is under their rule, let us resist in the smallest way: let their rule hold not through me! Our way must be: never knowingly support lies!"