Impressionists: The "gang" that captures the moment

The artistic movement of Manet, Monet, Cézanne and Renoir turns 150 years old. From the exhibition on the Boulevard de Capucines in Paris to painting gatherings "en plein air" in Argenteuil. A brief history of a revolution made up of awe and color.Given the serenity and happiness of the outcome, it is hard to imagine the convulsion and even confusion of the beginning, that April 15, 150 years ago. That day in Paris saw the opening of an exhibition by a ‘gang’ of artists, 28 to be precise, united by an elementary desire (and need) to exhibit their work to the public, since the doors of the annual grand Salon were systematically closed to them barred by a very conservative jury. They had come together by forming an association for practical reasons, without bothering to give themselves a common agenda. Most of those painters eclipsed in history, but eight made history instead: Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Jean-Baptiste Guillaumin, and Berthe Morisot. One artist was missing from the list, Edouard Manet, who had preferred to exhibit once again at the Salon des Refusés, the parallel exhibition to the Salon, proposed as an ‘official’ repair space for artists rejected by the jury.

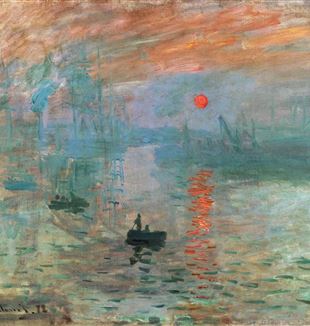

The ‘gang’ of those defectors had found a space in the former studios of the great photographer Nadar on the Boulevard de Capucines. The catalog was entrusted to Renoir's brother, Edmond: no pictures but a simple list of the 165 works exhibited. In addition to complaining about the delay on the part of so many artists, Edmond had lashed out at Claude Monet for the extreme monotony of the titles chosen for his paintings. "Put 'Impression,'" the artist had replied. The reference was to a view painted two years earlier at dawn at the port of Le Havre, Impression. Soleil levant. The painting’s title was destined to mark history, although in that circumstance it had become more of a pretext for all kinds of sarcasm, from the public and especially from the critics. That exhibition, which today features in all history books, had fairly modest numbers: 175 visitors at the opening, 54 on the last day. The Salon meanwhile was peeling off between eight and ten thousand tickets a day…It was a failure that had left some of the group's artists, Monet in particular, broke.

This is all part of a well-known anecdote about the birth of Impressionism. But what was the factor that was not understood at the time, but that instead determined the extraordinary posthumous success of that exhibition and that ‘gang’ of artists? There is one word that best helps to give an answer: "instant." It was Edmond Duranty, novelist and art critic, who had pointed to it in a book significantly titled La nouvelle peinture, published in Paris in 1876. Duranty had written that what united these very different, eccentric and instinctive artists was the desire to "capture the instant." This was the ‘novelty’ that the Impressionists were surprisingly injecting into the art scene, at once naïve and disruptive. So many dogmas that kept the artists locked in the claws of an increasingly rhetorical and stale academism, which claimed to impose its hegemony through the great annual event of the Salon, began to collapse one after another.

It had been like a sudden turn from night to morning, from darkness to light, from closed to open air. The painters, attracted by the charm and thrill of modern life, had abandoned the closed enclosure of the atelier and had discovered the wonder of the plein air. This was thanks to a small but invaluable innovation: the arrival on the market of oil paints packaged in tubes, which allowed them to paint anywhere without being constrained by the traditional paraphernalia kept in the atelier. Nature, with its freedom, became the teacher, taking the place of the pedantic guardians of rules now removed from history. And since in nature everything moves and each moment is different from the one that preceded it, the eye dictates the times and the hand must move fast to keep up with the visual perception recorded on the retina. The hand thus learned to move with a multiplicity of touches on the canvas, without worrying about the seemingly indefinite and fragmentary state of the image. "It is only an eye, but my God what an eye!" said Cézanne of Monet, the quintessential Impressionist, who more than anyone else in the following years would move closer towards this loss of the objective coordinates of vision. Nature acting as "teacher" taught that light is everything, that it ignites colors, blends them, fills everything with radiance, makes reality ever new.

Taken by this fever that was both of painting and of life, that very summer of 1874 a small group of veterans from the earthquake exhibition gathered in Argenteuil, on the banks of the Seine just north of Paris, some even to escape Parisian creditors. Seeing each other paint outdoors and in freedom was an experience that consolidated their self-awareness, overcoming even Edouard Manet’s reluctance. He is the person who in those weeks signed a painting that can be considered emblematic of the new: Claude Monet is seen with a model while painting on a boat transformed into a floating studio on the Seine. Even Manet, the most influential of the company, so observant of the rules of old painting, had been converted in Argenteuil to the irresistible lure of plein air. "Will these artists be the primitives of a great movement of artistic renewal?" wondered Duranty, writing on the heels of those events. And he gave himself the answer by remarking in wonder at "the audacity that leaps from those brushes." "Leaps," because that was the only way one could capture the wonder of the moment and document it on canvas.

Read also - Accompanying life, always

For those artists, painting did not mean returning to a generic and subjective impression of what was in front of their eyes, but giving back something that was very similar, each time, to a first glimpse at the world, with the astonishment and also the freshness that came with it. They were new painters because "they do not know," Charles Péguy had remarked when speaking of Monet's Water Lilies in the pages of "Veronique." Someone like Monet gave his best at the first glance, Péguy explained. He concluded, "It is the first that counts. It is the astonishment that counts, the undisputed principle of science."