"Trust the feel of what nubbed treasure your hands have known”

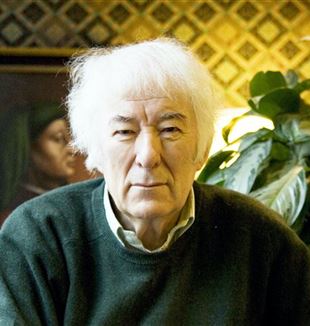

The Irish Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney died ten years ago. A Virgil in an age of uncertainty, recounted in the December issue of Tracce.Giampiero Neri, a Milanese poet who passed away this year, used to say that poetry never ends. It was his somewhat provocative way of explaining that art is not trapped in forms and canons. It is rather something wild, like a fawn crossing our path at night. Poetry is a moment of truth.

In his speech at the awarding of the 1995 Nobel Prize for Literature, Seamus Heaney related an anecdote that has the flavour of the poetry that Neri loved. It is about one of the most harrowing events in Northern Ireland's history. On an evening in January 1976, a van full of workers returning from work was stopped by the guns of a group of masked men. The passengers were forced off and lined up at the edge of the road. "Those of you who are Catholics, come forward," said one of the terrorists. All but one were Protestants. The conviction was that they had run into a group of pro-English paramilitaries. Stand firm and save themselves or make a gesture of heroic witness? The very instant the man started to move, he felt his Protestant neighbour trying to hold him back by shaking his hand, as if to say: “No one needs to know what faith you are.” But it was now too late. The Catholic worker was not even in time to realize that his Protestant comrades were shot down by a barrage of IRA bullets. The poet concluded: “The birth of the future we desire is surely in the contraction which that terrified Catholic felt on the roadside when another hand gripped his hand, not in the gunfire that followed, so absolute and so desolate, if also so much a part of the music of what happens. As writers and readers, as sinners and citizens, our realism and our aesthetic sense make us wary of crediting the positive note.”

Seamus Heaney was born in 1939 into a Catholic family in County Derry, in a village 50 kilometres from Belfast. He died in 2013 in Dublin, where he lived for more than 35 years. He earned his living by teaching, first in the Irish capital, then at Harvard and Oxford. The 1995 Stockholm speech marks a profound and enlightening synthesis of the meaning of making poetry and the way it intertwines with the dramas and dilemmas of life and history. The figure of Heaney, at the time of the awarding of the highest literary prize, was already known to the Irish people who considered his work a Virgilian guide in a time of great uncertainty.

His words accompanied readers in and out of Ireland as the island sank into the turmoil of the Troubles, a 30-year-long civil conflict. They were verses in a language that matched the tragedy before their eyes: “I shouldered a kind of manhood/stepping in to lift the coffins/of dead relations./ They had been laid out/ in tainted rooms,/ their eyelids glistening,/ their dough-white hands/ shackled in rosary beads.” Or: “Keep your eye clear / as the bleb of the icicle, / trust the feel of what nubbed treasure/ your hands have known.” And: “I am Hamlet the Dane,/ skull-handler, parablist/ smeller of rot/ in the state, infused/ with its poisons/ pinioned by ghosts/ and affections/ murders and pieties/ coming to consciousness/ by jumping in graves/ dithering, blathering.” But Heaney was not a civilised poet as one usually imagines him to be. Quite the contrary. Firstly, because his poetry was always linked to themes of the earth, rural life and nature, things transfigured from nothing through the sound of words and the precision of images. An example is the poem entitled Digging, digging: “Between my finger and my thumb / The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

The poem goes on to describe a noise coming from the window. It is the father digging the earth to plant potatoes. Then he evokes his grandfather who, years earlier, broke his back in a bog. “But I’ve no spade to follow men like them. / Between my finger and my thumb/ the squat pen rests. / I’ll dig with it.” It was a matter of sinking the blade of poetry inside the clumps of reality. And Heaney succeeds in the magic, which few people have, of digging in his own backyard – Ireland with its sounds and colours, ancestral myths and Catholicism – to extract nuggets of universal treasure. Thus even references to the very regional conflict in Ulster become a pool from which everyone can draw to come to terms with their own public, private or inner war.

In his Nobel speech, he explained that in the name of Christian morality he was inclined to deplore the atrocities committed by the IRA but, as a “pure Irishman,” belonging to the Catholic minority, he had grown up in the awareness of the injustices he had suffered and was horrified at the barbarity of the British army on Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972. He added: “What I was longing for was not quite stability but an active escape from the quicksand of relativism, a way of crediting poetry without anxiety or apology.” And in this regard he quoted a line from the American poet Archibald MacLeish: “A poem must be equal to/not true.” Emily Dickinson would say: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” The relationship between reality, poetry and truth is a dynamic triangle, whose sides lengthen and shorten and almost never do the three vertices lie on the same straight line. Yet, Heaney explained, there are times when a deeper need arises in the poet “when we want the poem to be not only pleasurably right but compellingly wise, not only a surprising variation played upon the world, but a re-tuning of the world itself.”

Can art really do anything to fix the world? "It is difficult at times to repress the thought that history is about as instructive as an abattoir," said Heaney. But in a poem he recounts the legend of the Irish monk Saint Kevin: " The saint is kneeling, arms stretched out, inside/ His cell, but the cell is narrow, so/ One turned-up palm is out the window, stiff/ As a crossbeam, when a blackbird lands/ And lays in it and settles down to nest […] Is moved to pity: now he must hold his hand/ Like a branch out in the sun and rain for weeks/ Until the young are hatched and fledged and flown […] Alone and mirrored clear in love's deep river,/ 'To labour and not to seek reward,' he prays,/ A prayer his body makes entirely/ For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird/ And on the riverbank forgotten the river's name.”

For the poet, Saint Kevin's is a realistic view of what happens in life, of those who know well “that the massacre will happen again on the roadside,” but also gives credit to the handshake. It is a view that “satisfies the contradictory needs which consciousness experiences at times of extreme crisis, the need on the one hand for a truth telling that will be hard and retributive, and on the other hand, the need not to harden the mind to a point where it denies its own yearnings for sweetness and trust.” There are many moments in which Heaney's poetry resembles a Scottish shower, which first tortures with temperature changes and then leaves one's limbs feeling relieved. Like when he speaks of his experience on the London Underground in District and Circle lines: “And so by night and day to be transported/ Through galleries earth with them, the only relict/ Of all that I belonged to, hurtled forward,/ Reflected in a window mirror-backed/ By blasted weeping rock-walls./ Flicker-lit.”

Read also - Love changes history

But, according to Heaney, there is another element by which poetry accesses truth. It is a factor that seems to contradict Giampiero Neri's principle, already mentioned: “In fact, in lyric poetry, truthfulness becomes recognizable as a ring of truth within the medium itself.”

As a poet, all his efforts have been directed towards “a strain, seeking repose in the stability conferred by a musically satisfying order of sounds.” The form – the rhythm, the alternation of similar and different sounds, the pauses of silence – is a fundamental element of the power of poetry, which is to “persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they, too, are an earnest of our veritable human being.”