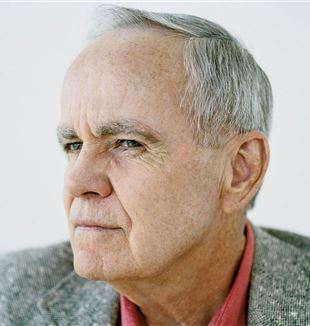

Cormac McCarthy: "I’ve encountered no greater mystery in life than myself”

One of the greatest contemporary writers died on June 13, at the age of 89. The Passenger is a metaphysical thriller with provocative questions about the essence of life. From the June issue of Tracce.There is a dialogue in the final pages - stark and powerful, like all those that fill the book - that has within it a question capable of jolting us from our reading, like certain words carved in relief: "If we are not after the essence, then what are we after?" It is true. What is the point of talking to each other, telling, writing - after all, living - if not for this? For him, it is. It always has been.

Cormac McCarthy is back. Sixteen years after The Road, the post-apocalyptic tale with which he won the Pulitzer, the American writer considered a classic even while he was alive (he would have turned 90 in July) has published two intertwined novels: The Passenger and Stella Maris. They were published together in the US in the fall. The first tells the story of Bobby Western, a scientist who gave up physics to devote himself to car racing and then became a "salvage diver," and his sister Alicia, a mathematical genius, who guides us to the heart of the world, that is, in search of the essence. Of the meaning of reality.

She committed suicide. We find this out on the first page, and the later chapters - where dialogues with Thalidomide Kid, the bizarre protagonist of her hallucinations, intersperse the flow of the story - gradually reveal why. It is impossible to resist such acute sensitivity, to the paradox of a reason that the more it gets to the bottom of things, the more it finds questions and mysteries there. It is impossible to experience the love he desires, because the object - reciprocated - is his own brother, and such a story drives inexorably toward loneliness and to the brink of madness.

He finds himself devastated by the loss, corroded by guilt and grappling with questions he cannot censor, because "if all that I loved in the world is gone what difference does it make if I’m free?" Ultimately, what is the point of living?

When work puts him in front of an enigma (when the plane he is supposed to rescue, which sank off the coast of New Orleans, has an intact fuselage, but the body of a passenger and the black box are missing), Bobby begins a journey of his own, on the run from disturbing characters who hunt him down (the FBI? spies?) and in search of the key to unlocking the mystery.

He probes his past, diving among his sister's letters and the papers of his father, a famous physicist in the group of scientists who created the atomic bomb. We follow their trail in a metaphysical thriller with little action, but with dialogues that address universal themes (including science, of which McCarthy was an enthusiast) and, above all, questions. Acute and deep, because they seek the essence.

This is McCarthy's hallmark, one of the (many) reasons why he was one of the greatest contemporary writers. He tackles only "matters of life and death," because "I don't trust authors who don't," as he said in one of his very rare interviews years ago; he fights "hand-to-hand with the gods" (Washington Post) and translates this struggle into stories: characters, situations, facts. The structure of his profound dialogues is so bare and lacking even quotation marks, yet his language is at once rich and essential, capable of bringing out of things a nostalgia that you cannot explain.

He describes trout swimming in a puddle (The Road) or a crimson sunrise on the majestic plains of Texas (All the Pretty Horses) or the burrow built by muskrats in a gorge, repairing "flawlessly" the hole that Bobby, a child, had made to look into it. Reading those half-pages of pure description - mundane scenes you've never seen, memories that don't belong to you - you feel something strange emerge inside of you.

What is so powerful about reality, capable of attracting you like that? And what kind of gaze does it take to be able to evoke it without talking about it? The point is that for McCarthy, simply, reality is alive. It overflows with life and mystery. Even in its most seemingly insignificant, dark, obscure corners.

Take Bobby for instance. It is no accident that he is a diver. "He is sinking into a darkness he cannot even comprehend," observes Shedden, one of his friends. As if his work physically recalls the strain of untangling everyone's questions, while above him the water flows with all its weight "endlessly, endlessly. In a sense of the relentless passing of time like nothing else." It is the work of all of us, willingly or unwillingly: to search in the opacity of reality for something that gives light - meaning - to the journey. To illuminate an imposing truth that one of the characters sums up in one sentence, "I’ve encountered no greater mystery in life than myself." For what is true of reality is even more true of man. The indecipherable darkness that so many times makes reality dark is a close relative of what we have inside.

Evil is a pervasive theme in McCarthy's work. He presents ruthless characters, capable of absolute, motiveless ferocity -- Judge Holden in Blood Meridian, the killer Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men – who are reminiscent of certain protagonists in Flannery O'Connor's short stories, because he lives the same questions. What happens in the human soul – and in society, in the universe – when meaning is lost? And whether or not there is something irreducible even to this, whether or not there is some glimmer of salvation capable of infiltrating the cracks of this race toward nothingness, and redeeming us.

"In The Passenger there is a very strong desire for dissolution," observed Antonio Monda, a literary journalist, at a recent meeting at the Milan Cultural Center. "But the longing for salvation prevails. It is stronger."

This happens on every page. In a dark world, which at first glance is sliding inexorably toward darkness, something else prevails. First of all, for the very fact that reality exists, and it has within it a most powerful life. It cries out a longing, a need for meaning. It is impossible to draw yourself away from the page of The Road without that dialogue between father and son, lost in disaster, rumbling in one's head: "We’re going to be ok. Because we carry the fire." It is all too easy to see in it a powerful metaphor: the relationship with Mystery. But it is much more than that. It is not just a symbol, it is the very heart, the essence of reality.

There is only one condition for delving into this hard, stainless core: wanting to look. Rather, to see. Luca Doninelli affirms that McCarthy "sees things there where we do not see them. We can reason well, but we reason about what we see and hear. And what we see and hear, normally, is little. He sees more than we do." In another dialogue, one of the characters says, "Everyone is born with the faculty to see the miraculous. Not seeing it is a choice." The light is there, always. But it is a matter of wanting to see it, of not choosing for nothingness.

Bobby's whole journey in pursuit of his past and in search of its meaning, his whole being as truly and profoundly a passenger – like each of us –, plays out on this subtle thread: being able to see. Indeed, choosing to see.

At the end of a long dialogue with his friend Debussy (a transwoman, one of the most beautiful and purest characters in the book), Bobby escorts her out of the bar.

"On the sidewalk she kissed him on both cheeks. All the time I’ve known you, I’ve never once asked myself what it is that you want.

From you?

From me. Yes. That’s very unusual for me. Thank you.

He watched her until she was lost among the tourists. Men and women alike turning to look at her. He thought that God’s goodness appeared in strange places. Don’t close your eyes."

Behold, open your eyes and God’s goodness. Our freedom and God. Who, in turn, appears often in the book. Evoked, alluded to or called by name. Inevitable, when talking seriously about life and death.

As Debussy herself shows in her purity, "I don't know who God is or what he is. But I don't believe all this stuff got here by itself. Including me. Maybe everything evolves just like they say it does. But if you sound it to its source you have to come ultimately to an intention…About a year after this I woke up again and it was like I had heard this voice in my sleep and I could still hear the echo of it and it said: if something did not love you you would not be here.”

If something hadn't loved you, you wouldn't be here. Wherever you are, wherever you are in history, whatever pain you are experiencing, whatever you have lost, there is something mysterious that comes first, and it loves you. It is a simple and irreducible truth. Millions of centuries from now, it will still be true. If we want to see it.

Because in the end, we are the passengers. The journey is up to us. The question that McCarthy leaves behind, after a lifetime spent "wrestling with the gods," is that posed by Sheddan, Bobby's friend: "Are we few the last of our lineage? Will children yet to come harbor a longing for a thing they cannot even name?"