The dangerous edge of things

Graham Greene died thirty years ago, on April 3, 1991. From the April issue of Italian Tracce, a journey through the works of one of the most renowned British and Catholic authors of the twentieth century.Telling a story is never a painless enterprise. The author must begin from their frailty; they must remove the armor of everyday life. The readers, for their part, recreate the story in their thought, in their rational and emotional feeling. This is true for any type of narrative as questions about the human always lurk deep inside.

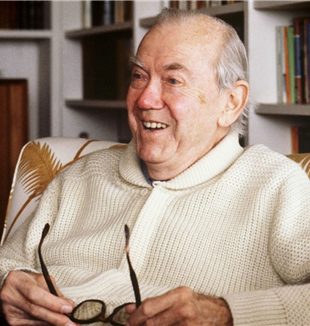

In the works of Graham Greene (1904-1991) this question is intense, urgent. Thirty years after his death, the British author is considered among the best of the twentieth century. Critics praise his ability to write stories of different genres - from crime to romance novels, from thrillers to existential drama - in a style that interweaves humor with introspection. More than fifty films have been produced from his novels. His stories are sharp as a sword, they lay us bare, they put us in a corner. The protagonists - and us with them - always end up asking themselves: who do I want to be, what do I really want?

Greene led a disordered life; he had a penchant for alcohol and especially for women. He worked for the British Secret Service and travelled the world, with a restlessness that made him move upon what he called "the dangerous edge of things." At twenty-two he converted to Catholicism. There is nothing apologetic in his books; indeed, the perception of divine presence often manifests itself as a torment. At the same time, however, there is an awareness that faith is stronger than any fear, any infidelity. This is not theorized, but is revealed in the flesh, in the characters’ contradictions. “If you are a Catholic”, said Greene, “you do not need to study how to ‘write like a Catholic’. Everything that is written and said can only be Catholic.”

His short story The Lottery Ticket, reflects Greene's vision, amid irony, tragedy, guilt and redemption. Henry Thriplow, "about forty-two, wealthy bachelor," goes on vacation every year to a remote and uncomfortable place, so that he can feel nostalgic enough to return home in peace. One summer, while he is "in a gloomy tropical state", where there is nothing but "swamps, mosquitoes, banana plantations", he happens to win the lottery. He is embarrassed, confused, he does not speak Spanish ... impulsively, he decides to donate the prize to charity. But he is deceived: a grim dictator uses the money to brutally consolidate his power. Eventually Thriplow, bitterly, wanders off into the night. Greene concludes: “As he walked in his disappointed exile beside the acrid river, it seemed to Mr. Thriplow that he had begun to hate the whole human condition. He remembered an expression of his childhood about someone who had loved the world so much, and leaning against the wall Mr. Thriplow wept. Mistaking him for a compatriot, a passer-by addressed him in Spanish.”

These few lines encapsulate everything of Greene. The exotic setting, which features in several novels, highlights the protagonist's loneliness, cut off because he knows neither the language nor the customs. Here, paradoxically, he is accepted only when he abandons his understatement to give vent to pain. Thriplow feels that he hates the whole of humanity because he has experienced firsthand what evil is, but just in that instant a memory seems to open up the possibility of redemption: "An expression of his childhood came to mind" .. Like a subdued echo, the words that Jesus said to Nicodemus came out: “For God has so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, so that everyone who believes in him will not perish but have eternal life" (Jn 3: 16-17). Faced with Nicodemus' doubts ("How can a man be born when he is old?"), Jesus reiterates that it is a "rebirth from above". Greene does not judge Mr. Thriplow, nor does he want his readers to do so, but he bids him farewell with a glimmer of hope.

The absence of moralistic judgement and the tension towards a "rebirth from above" are hallmarks of Greene's work. They are found in three fundamental novels.

The Power and the Glory (1940) takes us to Mexico in the 1930s, at the time of the persecution of Catholics. The protagonist is a priest, whose is never named. A vile, inadequate man. When he was parish priest in his village he was not only an alcoholic, but he also had a daughter from an illicit relationship. Yet this man, with all his serious defects, fully remains a priest. He is even capable of performing a heroic gesture, thanks to courage that comes from his weakness: “Tears ran down his face. [...] he only felt immense disappointment because he had to go to God empty-handed, with nothing done at all. [...] He felt like someone who had missed happiness by seconds at that appointed place. He knew now that at the end there was only one thing that counted – to be a saint.” Despite his anguish, the priest does not run away from his vocation, without taking anything of his frailty away. He is there, at the hour that gives meaning to an entire life. Everything else is mercy, Greene suggests.

The End of the Affair (1951) revolves around a love triangle against the backdrop of gloomy London, torn apart by Nazi bombings. Beyond the amorous affairs, the lives of Sarah and Maurice (wife and lover) hide the pain of rejected and sought-after faith. During the course of the novel, it is not rationalistic and doctrinal work that reveals the superabundance of grace, but rather the ineffable web of reality, of the facts and signs present.

A Burnt-Out Case (1960) recounts the adventures of Querry, a world-famous Catholic architect, famous for his majestic cathedrals. He is a man with a messy love life until, around the age of fifty, he realizes that he no longer interested in women and, above all, that he has lost his faith. He does not want to build churches anymore, because that would be a lie. He retires to the heart of Africa, in a remote leper colony that he comes to by chance. He stops there, determined to do something, even humble, to almost drown out his crisis.

In a dialogue, he is forced to face the crucial circumstance: "You are too troubled by your lack of faith, Querry. You keep on fingering it like a sore you want to get rid of. […] You must have had a lot of belief once to miss it the way you do.” Working alongside the lepers and in contact with suffering, he gradually experiences the possibility of rebirth: "Perhaps there he had found a homeland and a life". In the depths of abjection, in their distance from themselves and from the world, Greene's characters never stop questioning themselves. And suddenly, in a gratuitous, unexpected way, a thread of hope is regenerated.

Andrea Fazioli, born in 1978 in Bellinzona (Switzerland), is the author of novels and collections of short stories. Among the latest: Il commissario e la badante (2020), Gli Svizzeri muoiono felici (2018), L’arte del fallimento (2016). He teaches creative writing at the Flannery O’Connor School in Milan.