Thoroughly human

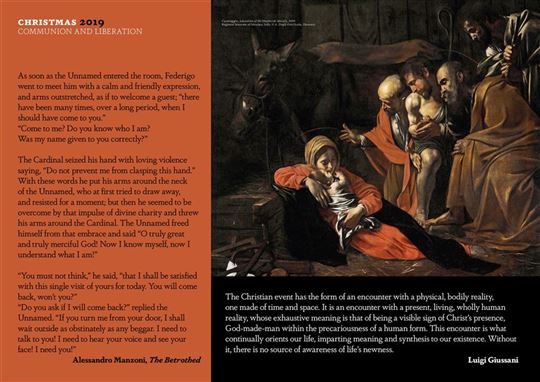

The image proposed by CL for this year's Christmas poster is from a masterpiece of simplicity by Caravaggio. The gazes of the shepherds are “conquered by what was before them,” and reflect the heart of the event that made God “a force close at hand.”A diagonal. A simple diagonal. The message of The Adoration of the Shepherds, a masterpiece from the most extreme times in Caravaggio’s life, is summed up in that diagonal line, which serves as the compositional and poetic architrave supporting the painting. The line begins in the upper right with the shepherd leaning on his staff and descends quite clearly, passing over the bald shepherd’s head before arriving at Mary, who holds the swaddled infant in her arms. Caravaggio crowds all the protagonists of the painting into the lower triangle traced out by the diagonal, but in the upper triangle, he has no hesitation painting something complementary: a large space that seems to contain nothing, so great is its poverty by comparison. (Giovan Pietro Bellori described it in 1672 as a “broken-down shack with its boards and rafters coming apart.”)

The force of that line lies primarily in the direction in which it points, from high to low. This is the defining fact of Caravaggio’s masterpiece. The gazes of the shepherds, who have come to see the infant, seem to plummet downward toward their feet, or, to express it in a way that is more faithful to the surroundings, to a point that lies on the bare dirt. Typically, you adore something that is raised up, crowned by light from the heavens. Here, instead, the parameters are turned upside down–Caravaggio’s painting, in its composition as well as its effect, points to the rough and bare earth.

The artist’s geometry is populated by an extraordinary density of humanity composed of the shepherds, driven by the scarcely restrained impulse to bend down over the infant. With them is the aged Joseph, on their left, identifiable by his halo and painted with a light touch. Their gazes are simple; they are gazes conquered by what is in front of them. That of the man first from the left is full of wonder; that of the second, visibly moved; and Joseph’s, simple and devoted. Mary sits on the ground, reclining with her elbow resting on the manger, her face half lit and focused on her little son, whose arms are reaching out for her. This is a truly humble Madonna, considering that the root of the word humility is humus, “earth.” She is cloaked in a bright red vermillion mantle, seemingly a metaphor for the expansion of a heart inflamed by an infinite love.

The iconography used may have been suggested to Caravaggio by his clients from Franciscan territory. The painting, now housed at the stunningly restored Regional Museum of Messina, was commissioned for the high altar at Santa Maria della Concezione, a Capuchin church destroyed by an earthquake in 1908. Furthermore, as Fr. Antonio Spadaro–a Jesuit from Messina and current editor-in-chief of La Civiltà Cattolica–has noted, the archbishop of the “city of the strait” at that time, Bonaventure Secusio, OFM, was a prestigious figure. In short, the gloomy Caravaggio, “a man with a restless, contentious, and turbid mind,” as Messina native Francesco Susinno described him, disciplined himself to accept the indications that came to him from the Franciscan commission, but in the end definitively surpassed them, with the ingenious simplicity that always brought him into contact with the heart of reality, laying bare the fullness of man’s sense of expectation.

As the great scholar of the art of Lombardy Ferdinando Bologna wrote, in paintings like this one, Caravaggio “brought the sacred into alignment with the living in order to bring the sacred concretely into the grasp of mankind… For him, showing its accessibility by way of ‘similarity’ meant freeing [the sacred] from abstract and isolating kinds of contemplation and revealing it to mankind in its deeply constructive aspect as a force close at hand.” This is precisely the point–Caravaggio saw Christmas as truly a “force close at hand.”