Andrew Tallon: The Witness of a Man

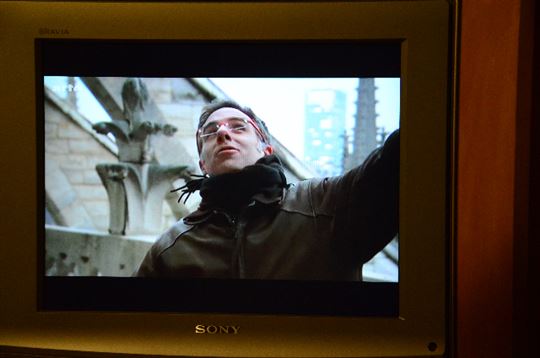

The research of late professor Andrew Tallon is serving as a scaffold for expert investigations on the Notre Dame fire. But Tallon was much more than a prestigious art historian. His witness of love for Christ shines as an example of concrete holiness.When the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris suffered a devastating fire in April 2019, the world mourned the irreversible damage of one of the world’s greatest monuments. News media covered the tragedy from every angle, and eventually outlets caught wind of the story of a recently deceased American professor whose work with high resolution laser imaging might hold the key to Notre Dame’s restoration. Such outlets as CNN, Forbes, CBS and others told the story of Andrew Tallon, whose work as an art history professor at Vassar College led him to pioneer the now familiar practice of using laser technology to produce precise images that reveal down-to-the-centimeter structural details of historic buildings. What these outlets omitted in their coverage, however, was Tallon’s profound witness of faith, particularly while confronted with the cancer that would ultimately take his life.

This witness began long before his groundbreaking scans or his cancer diagnosis. Jane Hubbard, Professor of Cell Biology and Pathology, became a dear friend of Tallon’s during their days singing together in a choir while he was in graduate school at Columbia. She recalls his wild hair and Converse sneakers, but what was most striking was the way he lived. “He understood Christianity not as a moralistic burden but as a liberating force. It was attractive. When we see someone alive and free it’s attractive,” she said.

Tallon’s work sprang from his zeal for his students, particularly undergraduates. His motto, said his wife, Marie Tallon, was “being there.” He wanted to teach in the famous buildings about which he lectured, even though his classroom was in Poughkeepsie, New York. He started exploring various techniques, and eventually had the idea to bring a laser scanner into a building. As he started scanning different buildings, he unlocked historical and architectural secrets. For example, at Notre Dame, he discovered that the building had shifted slightly over time. The revelation indicated that very early in the construction of the building, the two towers of the portal started to sink in the ground and lean forward, so the construction was interrupted for a few years, until the ground settled and they stopped moving. Then the construction started again. The upper parts of the towers show that the builders corrected the deformations still visible (thanks to the scanner) in the lower parts of the towers. He went on to scan numerous other buildings, but had a special passion for cathedrals, including Notre Dame. “He felt blessed to teach medieval art because he could share his faith in a way he couldn’t have done if he were teaching contemporary art. Those buildings were so imprinted by the faith of the people that built them. For him this was important. We cannot disconnect the two,” said Marie Tallon. “I don’t think he would have been interested in castles as much as cathedrals. It’s where Andrew wanted to be, that’s for sure.” His students were touched by his example, and Marie Tallon has since received many letters from them attesting as much.

“The spaces that he investigated were special to him in a number of ways. First, they were holy places. Second, they were architecturally interesting. They were acoustically interesting. And they were historically interesting,” said Hubbard. “His technology measured what ‘is.' It didn’t measure what the plans were. Not what was supposed to be, but what was actually present in reality. This was consistent with his outlook on life.” She compares the way he approached life to the recent School of Community on Morality: Memory and Desire. “Andrew is someone who I feel embodied that definition of the saint as someone who is realizing themselves. Every part of his life was guided by his first principles. He loved sacred music, sacred spaces. His family, love of France, love of his wife. There was a unity there.”

While he surely shared the beauty of the faith through his academic ventures, Tallon’s witness was especially evident in the way he faced his battle with cancer. In 2015 he was diagnosed with brain cancer and, at that time, was informed his life expectancy was likely short. Hubbard, who accompanied Tallon and his wife throughout his illness, recalls his unrelenting sense of humor in the face of it. Following a surgery in May 2017, two years after his initial diagnosis, Andrew and Marie Tallon desired to visit Lourdes. “This is hard to say today [as he has since passed away]. But I think we should call it a healing experience,” said Marie Tallon. At that point, he was in a wheelchair due to the brain tumor affecting his lower extremities. They spent the day there, and after Mass, he went into the bath. “And in the water he felt the presence of Mary and Christ next to him. At first he didn’t say anything, and we left and totally forgot the wheelchair.” Tallon had regained the ability to walk.

The doctors in New York could not explain his clinical improvement or the medical tests indicating the tumor was gone. But seven months after the pilgrimage to Lourdes, the tumor returned. He passed away in November 2018. “I know someday I will want to ask God why the tumor had to return, but I don’t think we should be afraid to call what happened at Lourdes a healing experience,” said Marie Tallon. It might be tempting to chalk it up to a psychological effect, but she said this would be disloyal to what actually happened. “He was touched in his body. It is the mystery of God as to why the healing didn’t last forever, and we have to trust. I told my son at the time, it’s a win-win. Either he lives and we’ll be happy or he doesn’t and God has a better plan for us.”

Hubbard recalls that Tallon had the 2018 Easter poster hanging in his room in the months before he passed away. It included the following quote from Msgr. Luigi Giussani: “Ever since the day Peter and John ran to the empty tomb and saw him risen and alive in their midst, everything can change. From then on, and forever, a person can change, can live, can live anew. The presence of Jesus of Nazareth is like the sap that, from within—mysteriously but certainly—refreshes our dryness and makes the impossible possible. What for us is impossible is not impossible for God. So that the slightest hint of a new humanity, to someone who looks with a sincere eye and heart, becomes visible through the company of those who recognize that He is present: God-with-us. The slightest hint of a new humanity, like dry and bitter nature becoming fresh and green once more.” He told Hubbard he looked at it often.

"I don’t think the story of a guy who made measurements of the inside of churches and the story of a guy who suffered in a particular way, or the fact that he was a father of four and had this beautiful family—these things cannot be separated. It goes back to the concept of unity of life. What’s important is that the very same thing that allowed him to experience his illness in the way he did is the same thing that allowed him to explore his work in the way he did.” Hubbard recalls that there were many people at his funeral who were not religious, but one neighbor’s (who was not someone of faith) witness was particularly striking. “The gist of it was that if he ever had to think about God, he thought it was what he had experienced with Andrew. The force of his personality was such as no one could deny it,” said Hubbard.

While Tallon did not witness Notre Dame burning, today his scans are serving as a baseline for architects and other experts in Paris studying how the cathedral sustained the fire. As devastating as the fire was, it sparked a renewed public fervor mirroring that of the medieval period. Even if rebuilding is politically motivated, or attention from the media ignores the fact that the cathedral is a house of worship, the fire demonstrates that we attach ourselves to a particular history, and this is in itself good. “If this can bring people back together and give them an identity, then we can thank God,” said Marie Tallon.

“I have two nieces in Paris,” she continued. “One sent me a video of people praying on the streets. If this can convert one soul, we can burn the entire building.” A cathedral weighted with centuries of history, art, music and faith has proven to be a profound witness. But how much more profound is the witness of a man.