Stargazing with "First Man:" A Most Human Experience

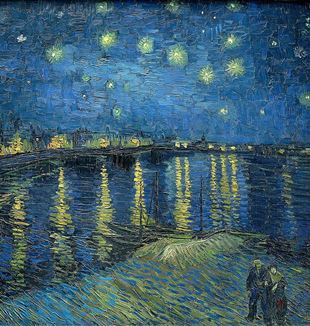

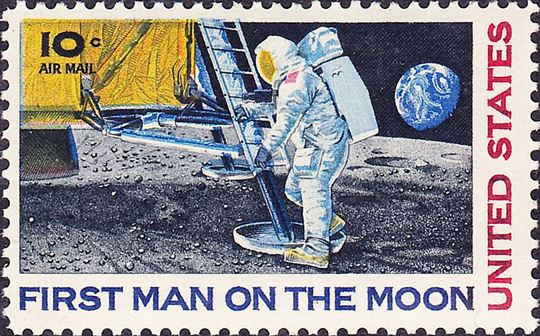

A short review of Damien Chazelle's movie "First Man," an account of Neil Armstrong and the events that brought him to the moon. The film is about "a man who truly seeks the infinite."It is not by chance that Dante used “stars” as the last word of the last line of each of his three canticas, the most important position of the poem. When Giacomo Leopardi gazed at the moon, he discovered the deepest and most human questions of his heart. Stargazing is in fact one of the most human experiences. Looking at the stars reveals our thirst for infinity, and need for something or someone that may answer to our desire, to the questions of our heart, to what we are missing. The very word desire comes from the Latin “desiderium,” which means “lack of (de-) the stars (sidera).” Desiring, therefore, ultimately means “missing the stars.” The latest movie by Damien Chazelle, First Man (2018) is one that exemplifies our human desire for the stars. It is the story of a man--Neil Armstrong--that for his whole life has looked at the stars. For this man looking at the stars was like looking at the infinite. No one had gone there before him.

This openness to the mystery, depicted not with the loud extremism of progress that often we hear about, but from the realism of the everyday life, is what most remains with the viewer. The familiarity comes also from the portrayal of Neil and Janet Armstrong, who are illustrated as people deeply interwoven with the reality of their daily life. In particular, Janet constantly recalls Neil to the totality of his human experience. The importance of Janet as an anchor of reality is suggested by the way the film is shot: for the majority of the movie the camera takes only the extreme close up of Neil’s eyes. His gaze is what leads the viewer throughout the movie, not simply as a point of view, but as a recording of his gaze on the world around him.

However, the second and very present protagonist of a similar angle is Janet. Their insistent eyes are almost uncomfortable. Particularly impressive is the sequence of the mission to the moon. Here, for the most part we only see Armstrong eyes. We don’t see the Moon, nor the Earth. We are only allowed to see his eyes looking straight at the moon, with the intensity that accompanies the possibility of the answer to one’s desire, the urgency of that answer, the consciousness that he is risking everything to experience that mystery. And yet, Neil’s silence in front of the unknown is broken almost exclusively by the song to which he dances with his wife, the only thing he has brought with him to the moon.

Opposite to the thrilling experience of the launch, this music offers probably the most moving moment of the entire movie. It shows us that no matter the fight between husband and wife, the fear that we read in Janet’s eyes, and the danger of the unknown, Janet’s urgent gaze keeps Neil grounded and propels him to the infinite. The trip to the moon therefore becomes a moment of truth, not only for the enterprise per se: shot in this way, it reveals that the most human position of a man, looking at the stars, is to desire to be complete, and ultimately the answer to that desire are the people that keep us attached to reality.

This movie is about the eyes, the gaze of a father, a man, a husband, a wife, and a gaze that takes us to the moon, to those stars that are at the bottom of our desire. One of the greatest movie directors of all times, Tarkovsky, in his Andrei Rubliev (1966), has one of his characters say, “You know very well, you can’t manage to do anything, you are tired, you are exhausted, and at a certain moment you meet among the people the gaze of somebody, somebody’s gaze, and it’s as if you approach the hidden divine, and everything becomes easier.” This movie reminds us that a man who truly seeks the infinite has a gaze that does not remain unnoticed, and that can move us too, to fully experience our humanity, and fully desire the infinite.