“Looking With Fresh Eyes to the Gifts We Have Received”

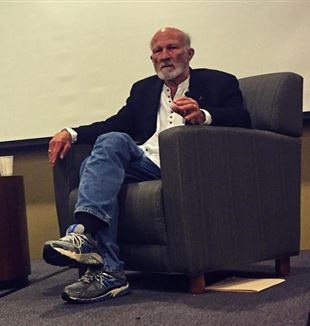

At the June 2018 National Diaconia, Protestant theologian Stanley Hauerwas shared his personal history, his journey of faith, and his appreciation of Fr. Luigi Giussani, in light of the challenges American Christians face today.Because of the desire to see how the recently released biography The Life of Luigi Giussani might illuminate the things that interest us—faith, society, education, politics, and more—we invited Stanley Hauerwas, the renowned Protestant theologian, to participate in the National Diaconia in June for a dialogue inspired by the book.

Our gathering started with a moving, impromptu prayer offered by Hauerwas, setting the tone for the entire conversation as a moment to be “surprised at one another in a way that reflects the glory of your Son, that the world might see we are not abandoned.” What followed was the engaging, intimate, and striking encounter with a person of great humanity and faith who, with his glance as a friendly outsider, helped us see with fresh eyes the gifts that we have been given by Fr. Giussani.

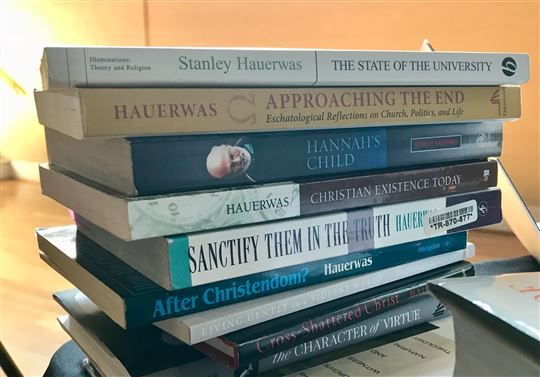

Hauerwas began by sharing a bit of his own story. He recounted how he was raised in Texas as a Methodist “of the evangelical sort” and how as a young man he set out to discover whether Christianity was true. After having become convinced that the Christian willingness to give up the Jews to the Nazi horror was the decisive challenge to the truthfulness of Christian convictions, Hauerwas discovered Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, two Christian theologians whose faith brought them to oppose the Nazi regime. “I started reading Barth’s Church Dogmatics when I was at Yale,” Hauerwas told us, “and it has never occurred to me to ask again whether I am a Christian or not. I simply cannot live without those witnesses making me more than I am.” He then quickly traced his path from a Ph.D. at Yale Divinity School to his work as a professor at Augustana College, the University of Notre Dame, and Duke Divinity School, where he now holds the position of Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Divinity and Law.

While narrating his personal story, Hauerwas touched upon the encounters with Catholic colleagues who introduced him to Giussani and invited him to the Rimini Meeting. Then, he started to reflect on the challenges that Catholics face in the United States by noticing that “Catholicism in America was an immigrant reality that made Catholics more Catholic than they would have been if they had stayed in Europe because you had Protestant prejudice to remind you that you were Catholics. Now the question is whether you can survive as Catholics after Protestantism has died. The great enemy of Christianity in modernity is not atheism, but sentimentality. Sentimentality is thinking that your children should not have to suffer for your convictions. I think the most important thing you can do is to help your youth to understand that being Catholic means that their lives might be put in danger, but otherwise, how boring would life be? I think reclaiming the adventure that is Christianity is part of the great challenge before you. This is the kind of challenge that we all face because mainstream Protestantism is in deep trouble as well.”

Afterward, the conversation turned to a discussion of Giussani’s take on the cultural revolution of 1968. Hauerwas thinks that this event, which in the US was connected to the moral chaos that led to the Vietnam war, marked the watershed in American history as it let us witness “the outworking of the heart of the American project.” This project is the best exemplification of “the project of modernity,” Hauerwas explained, “namely of the attempt to produce people who think they have no story except the story they chose when they had no story. We call that freedom.” Hauerwas noticed that this is exactly the opposite of what Christianity affirms. “We think we were born storied,” he said. “We are creatures of a good God whose love is so profound that God chooses to have companions—us. That means that you’re in great tension with some of the developments in American culture that are part and parcel of reactions against Christianity.”

For example, he elaborated, “Americans think they get to make their lives up. It never occurs to you as members of CL to think that you make Christianity up because it is something that you receive. It is received from people who have lived it well who want you to be their friend. I don’t want you to think that I’m deeply anti-American, though. I really cannot avoid feeling that I’ve been given a great gift by being a part of the American experiment, but it’s part of my loyalty to that experiment to say what its limits have been, and the limits have been pretty bad for Christianity.”

At the heart of Giussani’s proposal is the affirmation that Christ is the center of human life and that one can only know Christ in the church. Commenting on these emphases, Hauerwas shared that when he first read Giussani, he thought “he had anticipated Vatican II well before Vatican II. Vatican II is fundamentally Catholicism’s recovery of Christology being at the center of the faith. I’d like to think that you owe part of that to developments within Protestantism associated with people like Karl Barth. Giussani’s language of ‘Jesus as a fact’ is remarkable. Jesus is not some set of symbols about life having meaning or about the need to be loving to your neighbor. Jesus Christ is the Son of God. God refused to let our refusal determine God’s relationship with us. Through Christ, our lives have been made whole in a way that otherwise would not have been possible. We’re not talking about some set of truths that can be generalized independently of whether Christ existed or not. We are saying you have to have that first-century Jew to make sense of who we are as Christians. That was the turning of all that is. The question is never for us ‘Does God exist?’ but ‘Do we?’, because God’s existence is so surely found in the person of Christ that it is possible for us to know we have been loved and therefore we are to love God.”

Hauerwas continued his reflection, “How do you know that? There’s no Christianity without witnesses. One person tells another. That is the way Christianity gets around, and the name of one person telling another is church. If you want to know what salvation is, it is being pulled into this body of people that are the ongoing witnesses to the world that God has acted decisively through Jesus Christ making us an alternative to the world’s violence. That’s salvation. It is that bodily. It is that fleshly. My way of putting it is, ‘No Jews, no Jesus. No church, no Jesus.’ You have to have the ongoing physical reality of a people who have been dragooned by God into ongoing witnesses.”

While fielding questions from the audience, Hauerwas also engaged at length with Giussani’s understanding of experience. “Experience is a reductive term in Protestant theology. Protestant liberal theologians tried to show that any religious concept is fundamentally a description of human experience rather than God. Behind that is the development of Protestant pietism, the thought that your experience of salvation is more important than the Savior. I am part of a tradition represented by Karl Barth which is an alternative to that. I take it that Giussani’s use of the word experience is really a way of trying to suggest what it means to have learned to pray. That is an ongoing project for any of us: to know how to let God loose in our lives through prayer. I think that what Giussani represented was in some ways very simple, namely, that Christianity is not just about sustaining institutions, but it is about your life. Being a Christian makes possible for you to live in a way that otherwise you would not be able to live. That’s the naming of experience.”

There is another word dear to Giussani that Hauerwas thinks more important than experience. It is the word desire. “When people ask me ‘Why should I be a Christian?,’” he commented, “I oftentimes say ‘Do you like to eat?’ We were created as desiring beings whose fulfillment will be found in our complete ability to be in God’s presence without being burned up. I think desire is one of the most important things and one of the most important gifts we’ve been given because desire is God’s love compelling us to life with God.”

All throughout his life, Giussani also insisted on the importance of the liturgy, an emphasis that has characterized Hauerwas’ career as well. “The liturgy is the formation of our lives in the narrative that constitutes God's care of us through creation,” Hauerwas explained. “The calling of Israel. The impregnation of Mary. The life, death, Resurrection, and Ascension of Christ. That is the fundamental story that makes our lives intelligible. It's hard to remember. I have spent most of my life wondering ‘Where in the hell am I?’ I'm not sure I know who I am or where I am, so I can't wait for every Sunday where I get told again who I am, because without it I would be lost. Without the people that I worship with holding me to account, I wouldn't know who I am. In the liturgy, we are membered into the body of Christ in a way that makes it impossible for us to remember who we are without also remembering who it is that we are worshipping with. Liturgy is a remembering.”

Wanting to help us understand the environment in which we live, Hauerwas discussed at length the difficulties that Christians face in America, continually engaging with the many questions that people asked him. He warned us against the culture of greed in which we all live, he challenged us to be truthful in a world that too often relies on deception, and he confronted us with the sinful inclination of Christians to let their national loyalties determine their lives more than the church. At the same time, he was a powerful witness of the tireless energy that springs from the certainty of having being taken hold of by Christ. “There's nothing wrong with Catholicism that using the Book of Common Prayer wouldn't help,” he teased us. “Our closing prayer is ‘Eternal God, heavenly Father, you have graciously accepted us as living members of your Son our Savior Jesus Christ, and you have fed us with spiritual food in the Sacrament of his Body and Blood. Send us now into the world in peace, and grant us strength and courage to love and serve you with gladness and singleness of heart; through Christ our Lord. Amen.’ That means that through eucharistic celebration and participation, we have become Christ for the world. What an extraordinary thing.”

We have met a teacher. We have met a friend. As Hauerwas prayed with us, “Thank you for those gifts, Lord of surprises.”