Claudel: "See Impossible Things"

What bridges the individual and the cosmos? The Meeting of Rimini will be inaugurated by an adaptation of Paul Claudel’s "The Satin Slipper," bringing to the stage the Christian paradox in which the smallest detail is forever pierced by the eternal.The child / makes a racket and plays entirely freely, and eats what he wants / and sleeps as much as he needs. / But it is right that, when his season comes, the young man / in gazing upon the face of his woman, feels / penetrated by delight, / and that a power awakens in him, and that he looks at her as in the / April night / he looks at the garden whitened by lightning.

This passage from L’Echange expresses with peremptory clarity a crucial issue touched on throughout the oeuvre of Paul Claudel: that point of consciousness in which one becomes adult, reaching with one’s entire “I” and without excluding any part of one’s being, a maturity that unleashes a new freedom. For Claudel, freedom is always the consequence of an event, often a dramatic one. Such an event happens in The Tidings Brought to Mary, in which the characters must face the sudden departure of the head of the family, Violaine’s illness, and Mara’s betrayal. An important event also happens to Doña Prouheze, the main character of The Satin Slipper; she is a woman divided between three men, three reasons, and three visions of the world, through which she gains a new way of looking at things, a new way, and yet more precisely “her” way, of touching and possessing the entire world. In this work more than in any other, Claudel communicates to us that the narrow route through which one becomes an adult and grasps the totality of things is sacrifice.

The Satin Slipper, rewritten by Giampiero Pizzol and entitled Attraverso il mare del desiderio (Through the Sea of Desire) will inaugurate this year’s Meeting. “A mad quest,” explains director Otello Cenci, “that nobody in Italy has ever tried before. A universal story, the telling of how through many storms our heart can discover its safe harbor, its place in the world.”

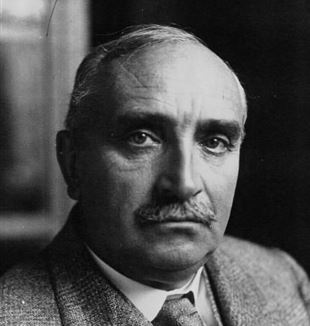

A new edition of The Satin Slipper is in and of itself an important event from a historical and cultural point of view: the enormous size of the work, united with the resistance Claudel’s work has always encountered, have meant that to date very few have had the opportunity to see it on stage. The Meeting is offering a crucial opportunity to see one of the great masterpieces of the 20th century, on the 150th anniversary of Claudel’s birth.

The choice to produce The Satin Slipper is particularly appropriate not only because of its historiographic value and the anniversary of the birth of its author, but also because it is extraordinarily pertinent to the title of the Meeting itself. The plot has a very simple narrative framework: in a legendary 17th century, Doña Prouheze, married to Don Pelagio but courted by Don Camillo, is profoundly in love with Don Rodrigo, who returns her love. This love will, however, never be consummated: the entire work is a development and exploration of the reasons for this renunciation, this sacrifice.

The whole world is brought onstage to celebrate the drama of human nature in front of the will of God. There is no place on earth that is not touched by the vicissitudes of The Satin Slipper: Europe, America, Asia, and the Orient are encompassed in an immense dramatic movement, a display of powers and of worlds that rotate around the story of a man and a woman who love each other without ever touching one other. However, the desire for the eternal and the infinite, for which not even the earth seems to be enough, is actuated in the earth and on the earth, in people and in relationships between people. Rodrigo and Prouheze cannot do without the world, the earth, the flesh, and yet all of it is never enough: they must surpass it, go beyond it. At the beginning of modernity, in which we still find ourselves, individuals come up against the drama of the fact that that they themselves are not sufficient for our desire.

The drama, pain, and sacrifice of the human being will give life to a new human person, touched by God, who is at once in nature, against it, and above it, in a mysterious paradox in which the characters of The Satin Slipper are the actors. “Joy alone is the mother of sacrifice,” says Rodrigo. “What joy?” the Chinese man asks him. “The vision of what she gives me,” responds Rodrigo. “Do you think the torture of desire is joy?” the Chinese man continues questioning him. And Rodrigo, “She has not read desire on my lips, but gratitude.” Every sacrifice flows from gratitude. Every renunciation erupts from our having received. Here we see how the personal drama begins to become cosmic: the actions of Rodrigo and Prouheze break natural logic, become testimonies that literally smash the structure of the known world. They break through it and make it transparent, and characters of different or even opposing orientations, cultures, and worlds–about which Claudel, a career ambassador, knew very well--glimpse an irresistible differentness, to the point of being drawn in by fascination and being changed. “The good that can come to me,” confesses Don Camillo, “seems more fearsome than the evil.”

“What I love,” Rodrigo says of Prouheze, “is not that which is turbid and ambiguous and uncertain in her, nor do I ask of her that which is inert and neutral and fleeting in her, but that which is the cause of her herself. It is the naked being, the pure life, that love strong like my desire, like a great raging fire, like the laugh appearing on my face!” Rodrigo discovers that he loves in Prouheze something deeper than the woman herself, even more profound than her “weak features:” the “naked being,” the “pure life,” a love stronger than both of them, strong like desire, things that make them alive even in the midst of sacrifice, that do not quench love, but rather, in sacrifice–paradoxically–save and fulfill them. A love that is great like the cosmos saves and fulfills the love of two individuals, small human beings closed in a drama that seems insoluble. This is shown well in the dialogue between Prouheze and the Guardian Angel:

Guardian Angel:

It was right that you made him know desire.

Doña Prouheze:

The desire of an illusion? Of a shadow that forever eludes him?

Guardian Angel:

Desire is of what exists, illusion is of what does not exist.

Desire through illusion is of what exists through what does not exist.

Desire, Claudel writes, is always authentic: it is always the flash of a truth. Even in this irregular and unfulfillable love, something immortal shines forth:

Doña Prouheze:

Will he love me forever?

Guardian Angel:

That which makes you so beautiful cannot die.

That which makes him love you cannot die.

Later, in the dialogue between Prouheze and Don Camillo:

Don Camillo:

Prouheze, you will truly be Rodrigo’s the day you cease to be his and are only God’s.

Doña Prouheze:

So to be Rodrigo’s, I must give up Rodrigo?

Don Camillo:

I believe that the cross will not be satisfied until you have obliterated all that which in you is not the will of God.

Here is how the space between the particular and the all, between the individual and the cosmos is bridged: the will of God, the loving embrace of the cross as the place of the greatest human splendor. This is the great Christian paradox that both fascinated and scandalized Claudel. This is the point at which “the forces that move history are the same that make men happy.”

In an era like ours, in which the cross “floats on the sea,” “at the point at which the limit of the known sky vanishes / and is an equal distance from the ancient world and the other new one,” only that which is “beyond the world” can challenge the reason “of the world.” Claudel shows us how even the smallest, most sordid detail can be pierced forever by the eternal, and in this way shine with a light never seen before, in such a way as to raise to anyone the question that Prouheze finally poses to Don Camillo: “Why could not your eyes, too, see impossible things?”