Looking out on "Campo G"

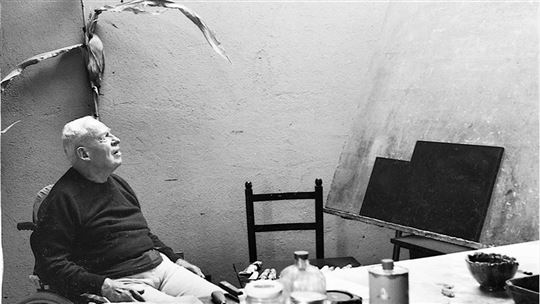

Twenty years after the death of William Congdon, three brothers at the Benedictine monastery known as the Cascinazza speak about life with the great American painter, and how he helped the monks live their vocation.William Congdon called the field outside the window of his studio at the Cascinazza, the Benedictine monastery, “Campo [Field] G.” This name referred to the first letter of the name of Giorgio Marognoli, one of the monks in the community that hosted the great American painter from 1979 until his death 20 years ago on April 15, 1998.

His choice of name for that little plot of land, one of the favorite subjects of his work from the beginning of the 1980s on, gives one a sense of the impact this community of monks had on both his artistic sense and his humanity.

Today, overcoming their typically reserved nature, Giorgio and two of his brothers, Claudio Del Ponte and Fr. Giuseppe La Rocca, have broken their long silence and accepted our invitation to speak about their “companion on the road.”

New York and Assisi. “He asked me to come to his studio pretty regularly. I looked at his paintings and offered a few thoughts,” Giorgio said. “The first Campo G originated at a time when he was unable to paint; he was stuck. It was shortly after he moved here. I said something to him that got the artistic juices owing again. He said to me, ‘Thank you, because you’ve given me the blood for my paintings.’”

The two had met in 1968 in the office of the newly-founded Jaca Book publishing house on Via Bagutta in Milan. Congdon had an active role in its establishment. “I met him there for the first time, but we really got to know each other later in Subiaco, where I had entered the monastery of St. Scholastica at the age of 21.” The American painter, a successful member of the “New York School” (as successful as another member, Jackson Pollock), had converted to Catholicism in 1959 in Assisi, and had been given use of the Beato Lorenzo hermitage above the Benedictine Abbey of Subiaco for a number of years. “I went to see him there. During times of recreation, I walked up there. He showed me his paintings, but at the time I wasn’t on the same ‘wavelength’ of his work.”

The old man. Congdon, who was born in 1921 in Providence, Rhode Island, was 56 at the time. He had met Fr. Giussani some time before, thanks to Paolo Mangini, his baptismal sponsor, who was 20 years his junior. Mangini was a member of the first Memores Domini house, in Gudo Gambaredo. On June 29, 1971, the Cascinazza was founded just a few hundred meters away from the house, and Congdon wrote: “I entrust my art to this monastery which, in turn, offers itself for this art; that is, it lays down its life of communion as the source of this art.” He did not know at the time that, a few years later, he would establish his studio and home inside the Cascinazza.

“Art had become the expression of his being a Memor Domini. This was what made him so great,” Giorgio says. “For him, painting was obedience to a gift. When he realized that a painting he had finished didn’t flow from his experience, he threw it out. He would say, ‘It came from the old man.’” Congdon’s diary is full of notes from conversations the two had: “November 10, 1979. Giorgio: ‘How do you remember the colors you’ve seen to paint them?’ Me: ‘The gift reminds me, and I remember the colors.’ Giorgio: ‘Exactly–art is a gift.’ Me: ‘Every gesture, when done in the Spirit, is a gift, is art.’”

Giorgio went on to say, “He considered this place an extension of the house in Gudo. And we welcomed him aware of this fact. We helped each other live our respective vocations. Every so often, he’d say to me, ‘I don’t see you, I see you as part of a body, the Cascinazza.’”

While Giorgio was talking about how he was a sounding board for Congdon on spiritual and artistic matters, Fr. Claudio decided to set the record straight: “As my confreres know, I was a little delayed in grasping the depth of his perceptivity and his artwork. Still, I was struck by the intensity of his gaze and his dramatic life. And, at the same time, by his childlike heart.” He told two stories: “One time he came to lunch, tasted the risotto and exclaimed, ‘Who made this?!’ [Here, Fr. Claudio imitated an American accent]. It was an ordinary risotto, but for him it was the best he had ever tasted. He knew how to live in wonder and be grateful. The other example of this was his careful preparation, especially in his last days, for when I came to bring him Holy Communion. He placed two lit candles on the table. It was his encounter with Jesus, who came to visit him at home.”

“More of a monk than I am.” Over the last 20 years, memories of the painter have often come back to Fr. Claudio. “I would almost say that Bill was more of a monk than I am, and God gave him to us as a priceless companion, especially because he was older than all of us; we were a pretty young community. He frequently came to Mass and prayed the Hours with us. He was a reminder of the profound nature of our vocation. I often found myself wanting to live with the same intensity he did. For him, nothing was trivial. He had a sense of humor; he was quite witty. For him, everything was a sign of the Mystery.”

When asked if he ever confessed his struggle to understand the art to the painter, Fr. Claudio answered with a smile. “St. Benedict says that each person has his gift, but with time I started to enter a little bit into his point of view.” Giorgio chimed in, “If he asked you what you thought about a painting and you didn’t answer, he’d say, ‘Your silence is very eloquent.’ If you told him it was ‘pretty,’ he would say, ‘You’re not looking at it right.’ If you told him you weren’t feeling the painting, maybe because of a color or an aspect of its composition you didn’t like, he would thank you. And maybe redo the whole thing.”

The monks were traveling companions for Congdon’s vocation and a help for his artistic work. Like the time when Congdon asked another monk, Bruno, to help him render the “woven” look of tilled fields. Within a few days, the brother found him a “comb” created from an old metal file. It was the inspiration for one of Congdon’s most beautiful series of landscapes.

Brother Giuseppe met Congdon before he came to the Cascinazza. While he was an architecture student in Milan (though he is from Messina), he invited the painter to speak at his university, as he had previously invited Giovanni Testori. When they first met in 1982, Congdon welcomed the college student with a typed letter. The first line said, “What could I possibly have to say to a young architect?” The last line read, “An artist prays by loving things, because he loves them with suffering.” It was the beginning of a friendship that would accompany Giuseppe along his entire path to becoming a monk. He still has the cards the artist wrote on the occasions of his entrance into the monastery, his investiture, and his solemn profession. “He took a liking to my dad because he said he reminded him of Igor Stravinsky, whom he met when he was living in Venice,” Giuseppe said. “When I first arrived, I had the job of cleaning the monastery, and when he heard me on the stairs to his studio, he would come out to say hello and to thank me.”

Attaining simplicity. From his binder of “keepsakes,” Giuseppe pulled out a clipping of the obituary Fr. Giussani wrote on the painter’s death. “In my mind, it’s the most beautiful ‘portrait’ ever done of Congdon.” It says, “The long years of his life ingrained in him an awareness that every work of art that owed from the depths of his creativity was a witness to himself and to the world of Christ’s presence. We are grateful to him for his friendship through which, in the simplicity he attained, he continually reminded us that beauty–tied to the memory of Christ’s death and Resurrection–is an expression of and introduction to the Truth of reality.” Giuseppe commented, “I saw how he attained that simplicity with my own eyes. He occasionally demonstrated the self-love and egocentrism common in artists, but each time he asked for forgiveness and started over. That ‘attained simplicity’ refers most of all, though, to his profound way of seeing everything. One time, I saw him so amazed at the light of a sunset that he went down into the courtyard in his underwear.” Giorgio added, “Right, I have the card he gave me the same day, ask- ing me if I had noticed it. He wrote, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever seen, from India to Africa, such a spectacle, such a heavenly vision as this evening’s sunset.’ It was beauty, the gift of beauty that won him over.”

Giuseppe tried to go a step further in his tribute. “What has stuck with me the most from him is a lesson about the unity between our vocation in this place and the historical task each of us has.” He pulled out another photocopy: the text of a talk Congdon gave at Abbiategrasso in 1982. “The death of my old life came about in Assisi in 1959, and from there God led me, agonizingly, step by step, to be planted in the desert-like plains of Bassa, outside Milan. It was only through my desperate ‘yes’ that God could stick me in the middle of hell.” Giuseppe said, “Bill was the person who, along with Fr. Giussani, most helped me to see this place as the one God chose for a task saturated with history. Now, when I think back on him, I’m filled with a sense of contrition that makes me ask myself, ‘Am I living with the same seriousness he had?’”

Remaining small. The three monks admit that, even now, it’s hard to look out the windows of the monas- tery without thinking of Congdon’s paintings.“I’m struck by the fact that the field looks different from the first floor than it does from the second floor, and this perspective is exactly what you see in his paintings,” Giuseppe explained. “Still today, I’m amazed.” “It’s like the field is coming right up to you,” echoed Giorgio, lifting his open palm toward his face.

Fr. Claudio related how the prior, Fr. Sergio, told Francesco, one of the latest arrivals at the monastery, about how important Congdon was for him. He remembered something the painter said over 30 years ago: “Look at what’s looking back at you! That rock... It’s Mount Tabor.” The rock that was the place of Christ’s Transfiguration. Francesco writes, “Though I only started to get to know him when I entered the monastery (18 years after his death), he is a witness to me that the method for reaching true knowledge is in remaining ‘small.’”